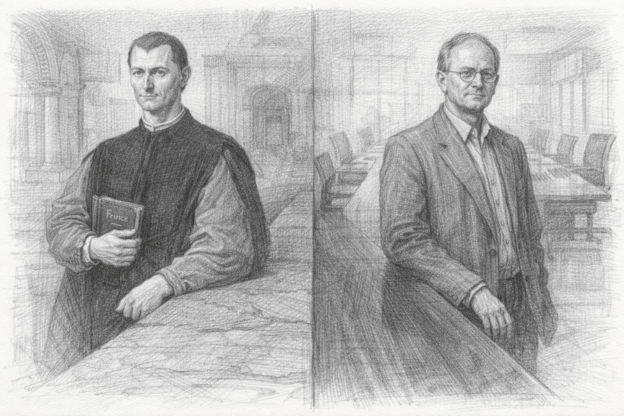

Comparing Jeffrey Pfeffer with Niccolò Machiavelli reveals a shared realism about power stripped of moral comfort. Both describe influence as driven by perception, control, and strategic action rather than virtue, and both expose why idealism so often fails in practice. Yet they diverge in intent: Machiavelli accepts harm as the price of order, while Pfeffer ultimately confronts the human and organisational costs of power-driven systems. Together, they show that the mechanics of power are historically stable, even as modern leaders are increasingly forced to reckon with their consequences.

Contents

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Are the Rules of Power Comparable?

- 3. Shared Foundations: Where Pfeffer and Machiavelli Align

- 4. Key Differences: Where They Diverge

- 5. Power Then and Now: Contextual Translation

- 6. Is Pfeffer a Modern Machiavelli?

- 7. What This Comparison Reveals

- 8. Implications for Modern Leaders

- 9. Conclusion

1. Introduction

Nearly five centuries separate Niccolò Machiavelli and Jeffrey Pfeffer, yet their work provokes the same uneasy reaction: recognition. Both writers describe power as it is practised rather than as it is preached. Both strip away moral comfort to expose the mechanics beneath authority, loyalty, and success. And both are routinely mischaracterised as endorsing ruthlessness when their real offence is honesty. Comparing The Prince with Pfeffer’s modern organisational studies reveals not a clash of eras, but a continuity of power logic across time, institutions, and cultures.

2. Are the Rules of Power Comparable?

At first glance, placing a Renaissance political theorist alongside a modern business-school professor risks anachronism. The settings could not appear more different: city-states versus corporations, princes versus executives. Yet comparison becomes unavoidable once the surface details fall away. What remains is not historical coincidence, but a shared concern with how power behaves under pressure—when ideals falter, resources are scarce, and survival depends on influence rather than intention.

Yes, strikingly so. Despite different contexts, Machiavelli and Pfeffer articulate structurally similar rules of power, adapted to different arenas.

While Machiavelli’s broader work—particularly the Discourses on Livy, reveals a preference for republican stability and a more complex notion of virtù, The Prince remains his most unvarnished account of how power is seized and held under conditions of fragility.

- Machiavelli writes for princes ruling fragile states.

- Pfeffer writes for individuals navigating complex organisations.

Both assume:

- Scarcity of power

- Competition for a position

- Human inconsistency

- Institutions that reward results, not intentions

The difference is not in whether power operates this way, but where and how openly it is acknowledged.

3. Shared Foundations: Where Pfeffer and Machiavelli Align

Despite their distance in time and context, both authors begin from the same refusal: they will not explain power in the language people prefer. Instead, they describe it in the language it actually uses. What emerges is a set of recurring patterns—lessons learned not from theory, but from observation of failure, competition, and fragility. These foundations are uncomfortable precisely because they feel familiar across centuries.

3.1 Power Is Not Moral… It Is Instrumental

Machiavelli famously separates politics from Christian virtue. Pfeffer does the same with leadership.

- Machiavelli: A ruler must learn “how not to be good.”

- Pfeffer: Ethical leadership rhetoric does not predict who succeeds.

Both argue that moral behaviour is optional unless enforced by structure.

3.2 Appearances Matter More Than Reality

- Machiavelli insists a prince must appear virtuous, even when acting otherwise.

- Pfeffer shows that confidence, image, and narrative outweigh substance.

In both frameworks:

- Perception creates legitimacy

- Reality follows reputation, not the reverse

3.3 Fear Outperforms Love (in Practice)

Machiavelli’s most infamous claim—that it is safer to be feared than loved—has a modern analogue.

- Pfeffer shows that being liked does not correlate with power

- Authority comes from control, not affection

Both warn that dependence, not goodwill, sustains power, Machiavelli noting that while love and fear together are ideal, fear is more reliable when affection cannot be guaranteed.

3.4 Power Must Be Used or It Erodes

- Machiavelli warns that hesitation invites rivals.

- Pfeffer notes that unused power decays quickly.

Inaction is interpreted as weakness in both systems.

4. Key Differences: Where They Diverge

Similarity should not be mistaken for equivalence. The distance between Machiavelli and Pfeffer matters as much as their alignment. Their disagreements are not about whether power operates harshly, but about what that harshness means, what ends it serves, and what responsibility follows from recognising it. These differences reveal how realism can harden into acceptance or evolve into critique.

4.1 Scope of Harm and Accountability

- Machiavelli accepts violence, deception, and cruelty as legitimate state tools.

- Pfeffer documents harm but stops short of endorsing it.

Pfeffer describes damage; Machiavelli accepts it as necessary.

4.2 End Goals of Power

- Machiavelli seeks state stability and survival.

- Pfeffer focuses on individual advancement within institutions.

Machiavelli’s power is teleological (toward order).

Pfeffer’s power is positional (toward advantage).

4.3 Moral Reckoning

Machiavelli offers no apology.

Pfeffer eventually does.

In Dying for a Paycheck, Pfeffer confronts:

- Health impacts

- Psychological harm

- Systemic toxicity

This marks a critical difference: Pfeffer becomes a critic of the system he explains, while Machiavelli remains a realist without remorse.

5. Power Then and Now: Contextual Translation

Power rarely announces itself in the same language twice. The forms it takes are shaped by institutions, technologies, and norms, even as its underlying logic persists. Translating Machiavelli’s world into Pfeffer’s does not flatten history; it clarifies it. The exercise reveals how little the core mechanics of influence have changed, even as the instruments and arenas have been thoroughly modernised.

| Machiavelli (The Prince) | Pfeffer (Modern Organizations) |

|---|---|

| Territory | Organizational turf |

| Armies | Resources, budgets, headcount |

| Nobles and elites | Executives, boards, sponsors |

| Court politics | Corporate politics |

| Public image | Personal brand |

| Rebellion | Career derailment |

The mechanisms persist; the weapons change.

6. Is Pfeffer a Modern Machiavelli?

The temptation to label Pfeffer a contemporary Machiavelli is understandable—and misleading. The resemblance lies in method rather than motive. Both describe power without sentimentality, and both provoke moral outrage for doing so. But their work ultimately points in different directions, shaped by distinct assumptions about reform, responsibility, and the possibility of restraint within complex systems.

In method: yes.

In intent: no.

Both:

- Reject idealism

- Describe power empirically

- Anger moralists

But Pfeffer’s work ultimately asks:

If this is how power works, what are we going to do about it?

Machiavelli asks only:

If this is how power works, how do you survive it?

7. What This Comparison Reveals

When placed side by side, these works illuminate more than each does alone. Patterns that appear cynical in isolation begin to look structural. Discomfort that feels personal reveals itself as historical. The comparison exposes not only how power works, but why societies repeatedly struggle to admit what they already sense, and why denial remains such a reliable ally of those in control.

- Power logic is historically stable

- Institutions change faster than human behaviour.

- Ethical discomfort is not new

- Every generation rediscovers power’s ugliness.

- Denial benefits incumbents

- Silence preserves asymmetry.

- Transparency is the modern differentiator

- What Machiavelli whispered, Pfeffer documents openly.

8. Implications for Modern Leaders

Understanding power is no longer optional, but understanding it is no longer sufficient. Leaders today operate in environments that demand both effectiveness and justification, realism and restraint. The lesson that emerges from Machiavelli and Pfeffer together is not how to win at any cost, but how costly winning becomes when power is mastered without reflection, and how fragile leadership is when reflection replaces literacy.

- You cannot escape Machiavellian dynamics by pretending they are immoral.

- You cannot rely on Pfeffer’s realism without confronting its costs.

- Leadership today requires power literacy plus moral agency.

The danger is not learning how power works.

The danger is learning it and stopping there.

9. Conclusion

Machiavelli and Pfeffer are separated by centuries but united by clarity. Both refuse to lie about how power operates. Where Machiavelli equips rulers to dominate, Pfeffer equips professionals to understand, and potentially reform, the systems they inhabit. The comparison forces a modern question Machiavelli never asked: not just how to gain power, but whether success is worth the system it sustains.