A memoir of nine years at Sun Microsystems, from the revelation of “The Network is the Computer” and parachuting into nasty projects, to the culture of contrarianism, the pressures of leadership, press training in Nice, and the slow decline into redundancies that culminated with Oracle’s takeover. It closes with reflections on philosophy, craft, people, and the enduring value of diversity and neurodiversity in engineering.

Contents

- Contents

- Prologue: Before Sun

- The Revelation: “The Network is the Computer”

- Joining Sun

- Nine Years of “Nasty Projects”

- Culture at Sun

- Why It Was My Dream Job

- Making a Difference

- Responsibility and Addiction

- The Press Training in Nice

- Redundancies and the “Sick Antelopes”

- Then Came Oracle

- What Remained

- Conclusion

Prologue: Before Sun

I started out as a programmer, or, in posh parlance, a “software engineer”. Not an “architect,” not a CTO, just a bloke writing C, Delphi, Fortran, CoBol, Oracle PL/SQL, assembly code, and whatever else the job demanded.

Being a programmer is great. Being able to write PL/SQL is great. Being able to poke at registers or knock out some assembly code is great. But the real craft isn’t in any single one of those. It’s in the combination.

That’s the fragile bit, and the valuable bit. The analogy I often think of is Richard Wilhelm’s translation of the I Ching. Carl Jung wrote in his foreword that it’s the combination, the interplay of symbols, the network of meaning, that gives it power. It’s the same with systems. A clever module on its own is fine, but the magic happens when you take hostile pieces and force them into some kind of handshake.

And you know what really made it fragile? The absence of documentation. Absolutely no documentation anywhere. You had to learn the parts no one else even saw, never mind understood. And that became my craft: going after the invisible bits. The parts where two systems met and either quietly worked or noisily failed. That was where the value lived.

The Revelation: “The Network is the Computer”

Around 1994 or ’95 I came across Sun’s line: “The Network is the Computer.” John Gage coined it, Scott McNealy evangelised it. For me, it was a revelation. I think I first saw it in the IT newspaper Computing.

Most of the industry still thought of computing as “the box.” Sun reframed it: the network itself was the computer. Software wasn’t tied to a single host anymore; it lived across nodes, moving and talking. HOL IS TIC.

That clicked with what I was already feeling as a programmer. Knowing C or Oracle was fine, but the real test was whether you could make them work together, and at scale. The value wasn’t in isolated expertise but in combining mismatched parts into a coherent whole.

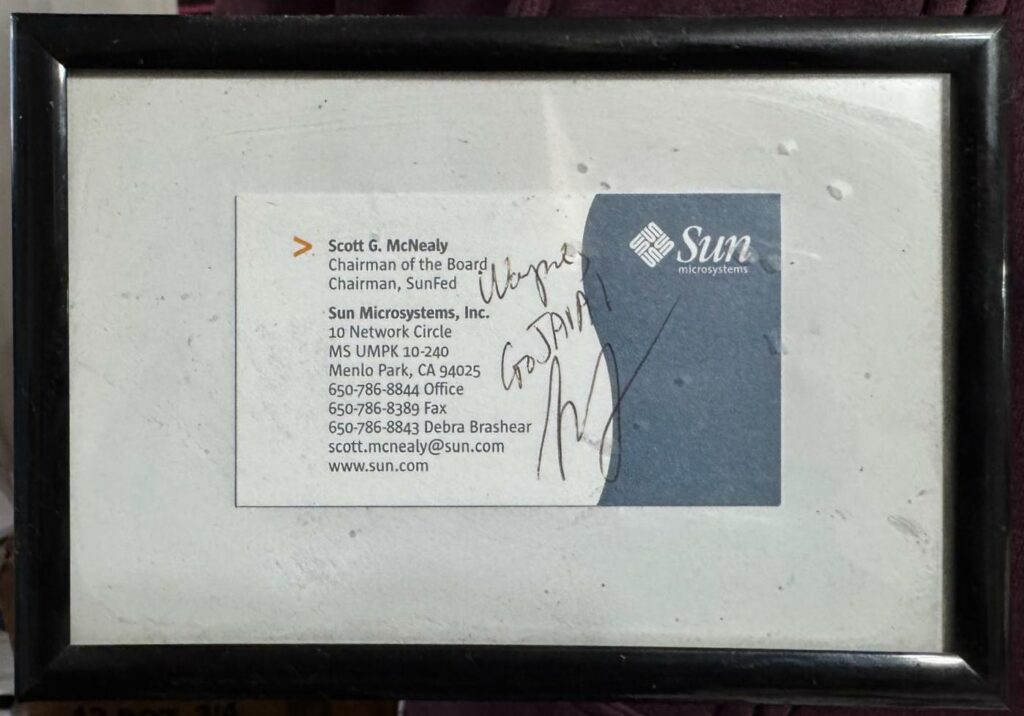

And I fell in love with Sun. I idolised Scott McNealy. Later, when I was CTO for the UK and Ireland, I got to meet him a couple of times. Meeting Scott was like meeting the bloke who’d written your favourite song; I felt like he was the guy who gave me permission to open the door to being amazing.

Joining Sun

By the time Sun called, I’d already built a reputation for enjoying “nasty projects”. The sort where everything was already on fire when you walked through the door. Most people hate those. I liked them. You learned really quickly, people left you to it, and they were grateful for the work you did and the outcomes you delivered.

Before Sun I’d already:

- written Statistical Process Control (SPC) systems and reporting for predicting manufacturing downtime in the automotive industry

- written the messaging system that let consumers swap energy suppliers during the massive deregulation of the energy market

- built the first set of firewalls in use at NatWest

- replaced twenty-six warehouses of documents for SunLife AXA with WORM (“write once, read many”) devices and early workflow systems

- built Harrods Online as the world’s first internationally shipping webshop and retail outlet

- built out the first generation of streaming at Fulham Football Club

At Sun, I suddenly found myself in the bloodstream of the internet. Solaris humming away under serious workloads. Java was becoming the enterprise lingua franca. XML was being stuffed into every conceivable message format. Netscape servers proliferated; at one point, over 80% of businesses ran their websites on Netscape on SUN kit.

And I didn’t just drift from project to project. I tracked them, every single one. By the time I left Sun, I’d worked on over seventy projects. For each one, I logged the technology stack, the business drivers, the data flows, the infrastructure, and the architectural quirks. I wanted the richest possible map of my own capability, systems engineering, enterprise architecture, infrastructure design, pen testing, performance tuning, securing systems, and designing large-scale architectures.

It was heady. It felt like being handed a seat at the table where the modern internet was being assembled. It felt and was true meritocracy. It didn’t matter that my autistic compulsion to swear was on fire; I was an in-demand technologist who could help customers lead successful projects and programmes.

Nine Years of “Nasty Projects”

At Sun, I became the bloke you parachuted into the burning building. Government platforms crumbling under traffic. Financial reconciliation and trading systems choking on their own complexity. Telcos weighed down by the sheer volume of transactions. Defence projects kludged together with grey-market kit.

The work wasn’t glamorous. It was about measurement, diagnosis, and discipline. First, instrument the system properly, watch the queues, the message sizes, the throughput. Then apply the fixes that actually mattered: right-size the app servers, stop the database being abused as a cache, pull out the “clever” brittle hacks some bright spark had left behind.

And then you stayed. You didn’t vanish after the handover. You lived in the basement for the first 48 hours of production, because that’s when reality tells you what you missed.

I did pen testing, too. I hardened systems. I improved the speeds and feeds. I designed architectures meant to survive hostile traffic, hostile users, hostile conditions.

That’s where I was most alive. There’s a satisfaction in seeing a system that wheezed at 3,000 requests a minute hold steady at 25,000, not because of magic, but because you respected the physics of the workload.

I’ll never forget a call I got from Alan Mather. “Wayne”, he said, “we’ve got this project, it’s fallen apart, it’s a mess. Will you come and help sort it out?” I laughed and told him, “Alan, I’d be honoured, but wouldn’t it be nice if once you called me at the start of a project, where I could help set strategy and set it up to succeed?” He chuckled and said, “Wayne, if we did that, how would we know we needed you?” It was validation, really. I was the bloke people like Alan rang when it was so bad that there was no hope left. To an extent, I was like Mr Wolf in Pulp Fiction: the fixer of last resort. And I’ll admit, it was flattering.

Culture at Sun

Sun wasn’t perfect, but at its heart, it was an engineer’s company. People like Bill Joy, James Gosling, and Andy Bechtolsheim had authority because they had built things. Inside Sun, you could argue fiercely, be wrong, get corrected, and walk out better for it.

And for a time, we were everywhere. Solaris on big iron. Java in every enterprise strategy deck. Netscape servers handling traffic that would have melted racks a few years earlier.

The truth is, the dot-com boom was built on Sun. The late ’90s and early 2000s, if you were online, you were almost certainly touching Sun kit somewhere along the way. We were the scaffolding of the web.

What Sun really celebrated was contrarianism. The company thrived on dialectical materialism, two opposing views smashing into each other until a better idea emerged. You could stand up in a meeting and tell someone difficult truths, and nobody would punish you for it. Sun loved hard-headed, stubborn engineers. They wouldn’t have hidden Barnes-Wallis or Tommy Flowers in a cupboard; they’d have put them on stage.

That celebration of stubborn brilliance was part of Sun’s DNA. It wasn’t always comfortable, but it made the work better. And it could occasionally let the odd chancer through whose position was based on dead men’s shoes and not quality. But thankfully, those sorts had to suck up to Americans to maintain their positions; the rest of us just had to deliver.

Why It Was My Dream Job

Sun was my dream job because, at heart, I’m an engineer. That’s all I’ve ever lived for: to build, to create. For me, engineering is the nearest thing to the divine. The act of creation; it’s spiritual. It’s the only thing that really engages me fully. All the noise of life falls away when you’re making something real.

So being CTO of the UK and Ireland, CTO of an engineering-led company, was huge recognition. It was a huge validation of me. And it was Sun. The place where I met the most extraordinary engineers I’ve ever known. You’d meet someone in the Coventry office and they’d casually mention they’d built the ID system for Barclays Bank, or they’d been part of the team that invented NFS. It was ridiculous. Everywhere you turned, there were patents, breakthroughs, and applied science.

And that’s what I loved: practitioners. Not just theoreticians, but people who took knowledge and applied it to real-world problems, delivering outcomes. That’s what Sun was. And there I was, CTO of the UK and Ireland, in a country I love, being part of an engineering culture that valued creation above all. For me, that was everything.

Making a Difference

It wasn’t just a title. We were able to make a difference, a massive difference.

We reorganised the engineering teams to be industry-focused, so they could pick up the semantics and language of their customers. That mattered. It meant our people weren’t just techies parachuted into alien territory; they spoke the domain, they understood the business, they could translate need into system.

We applied enterprise architecture mapping techniques to customer estates so that we could see the whole, sell into it better, and design solutions that actually fitted.

We designed the Sun Software AG disk box, which went on to massively replace the Microsoft disk box across the public sector, especially in local government. And we replaced the largest disk infrastructure in the UK, HMRC’s PAYE returns system. For four years in a row it had collapsed under Microsoft kit that simply couldn’t scale. We rebuilt it on Sun kit, and from then on it never made the news again. We scaled it. We fixed it. Quietly, effectively, permanently. That too is another story for another day soon.

I wasn’t just shaping systems, I was nurturing people, bringing staff forward, running workshops on EA mapping, pushing business-language thinking, and backing the four industry-based CTOs who carried that model into the field. Watching them grow and watching the teams engage with customers more deeply was every bit as rewarding as the technology itself.

That’s what was special. It wasn’t just about being CTO, it was about knowing that the work we did, the changes we made, kept whole systems, whole government functions, from falling over.

Responsibility and Addiction

I became CTO for the UK and Ireland after first serving as CTO for Public Sector. By then I was leading around 440 technologists, and most of my life was spent in airport lounges, government offices, and data centres.

I found I was good at it, translating between ministers, perm secs, senior customer executives, and CIOs on one side, and engineers on the other, without lying to either. That’s a rare skill, and it mattered.

But it also fed something dangerous in me: the need to be needed. When that many people look to you for answers, it validates you in a way family life never quite managed for me. I was more alive at work than I was at home with Donna. That imbalance cost me, and I regret it.

Roughly a third of my time was on paid projects, a third on sales engagements, and a third on staffing and managerial processes. Juggling those thirds made me sharper, but it also pushed me further away from home. That, coupled with the fact I ploughed a ton of time into representing Sun in terms of Professional representation Organisations like the IET, the BCS, the WCIT, and others. I even got Sun UK, to adopt the UK IT worker skills framework, SFIA (“Skills Framework for the Information Age”) licensed via the BCS, which was later adopted corporate-wide. The BCS even put me on their Council and the IET in their Digital panel.

The Press Training in Nice

Somewhere in the mix, I was sent on press training. The idea was to prepare me for Gartner’s big Symposium in Nice, around 2006 or 2007. Gartner had their set-piece essays; Sun wanted its UK CTO to be visible.

The training itself was maddening. The line was: you can talk about products, and only about products. Nothing about the real work we were doing in the UK. Nothing about strategy or the messy realities I lived every day.

I found that unbearable. The autism made it worse: being told you may not talk about the truth felt like being gagged. I ended up in real pain, stomach in knots. My flight was cancelled, I slept the night on the floor of Nice airport, and the whole experience just underscored how upside-down it had become.

Press training was supposed to prepare me for visibility. Instead, it nearly broke me. And later on, it would come back to bite me in far more dramatic fashion, but that’s another story.

Redundancies and the “Sick Antelopes”

At its peak, Sun was a $15+ billion global business. The EMEA arm alone was around $4.6 billion, and the UK contributed about £1.4 billion, which we held steady over a three- or four-year period. We were performing well while other regions struggled. But we were not immune to the larger corporate mistakes.

First, Sun got bitten by the grey market. We sold a load of kit through unofficial channels; the grey market flogged it cheap, our new kit looked overpriced in comparison. That bled revenue.

Second, we cannibalised our own pipeline and partner network. We ended up selling against our own partners, which was lunacy.

And then, the final nail in the coffin: Jonathan Schwartz, the long-haired lothario who succeeded Scott McNealy as CEO, pushed a “software first” strategy. The problem was we weren’t Microsoft. Technology-wise, we were much more rounded, more akin to SGI, marrying hardware, software, and services. Going software-only gutted the model and confused customers no end.

The truth is, redundancies had already started before Oracle swooped in. I ran one programme in 2007, making around 200 people redundant, with a gap in 2008. The HR metaphor used by the Sun HR person seconded to us to help run the initial redundancy process still astonishes me: “Imagine yourself as a lion, pruning the sick antelopes from the herd”. That was their language. I was flabbergasted. Engineers who had built the backbone of the internet were reduced to livestock in a PowerPoint slide, lost in a spreadsheet of who was “strategically” valuable, or not.

I knew how brutal redundancies could be because I’d lived through them as a son. When my dad was made redundant, it broke him. The man who’d been tough as old boots with me just collapsed inside. He spent three years drinking, stuck in bed, unable to cope. It hollowed him out. In the end, he took his own life. All of that stayed with me. So when it came to running my own redundancy programmes, I couldn’t just treat it as numbers on a spreadsheet. I felt the weight of every conversation, because I knew how easily it could ruin a life.

I attended every single exit interview personally. I made sure everyone had the chance to look me in the eye and ask me “why?”. I couldn’t stomach handing them off to HR, not when I knew what it felt like on the other side of the table. So I sat in each one, face to face. Some of them still stick with me. In one meeting, a bloke looked at me and said, “But Wayne, I was at your wedding.” All I could manage back was: “It’s not personal. The company has to be fit enough to survive and make money.” It sounded thin even as I said it, but it was the only truth I had. And it cost me. Those conversations piled up in my head. I took them home, and I carried them into therapy. People’s lives wore me down more than I ever wanted to admit at the time.

Then came the IBM debacle. Jonathan Schwartz had spent the better part of a year trying to sell Sun to IBM at a decent share price. The deal went to regulators, IBM blew hot and cold, and in truth, they were never serious. It was brinkmanship, game-playing. When IBM finally walked away, Sun’s stock collapsed, wiping out roughly a quarter of its value in a single blow. One of the most embarrassing sales negotiations I’ve ever seen.

The collapse of that deal didn’t just humiliate Sun; it left us exposed. With the stock price in free fall and morale shot to pieces, we were a sitting duck. And that’s when Oracle swept in. Bargain-bucket price, opportunistic timing. It was brutal to watch.

Then Came Oracle

In that first year, 2009, Oracle introduced a staff reduction programme, taking out anybody not aligned to their strategic vision of Sun hardware existing to run RDBMS workloads. This resulted in the loss of another 200 heads. That was it.

At the end of that round of redundancies, Oracle’s UK CEO called for me and let me know they didn’t need a UK CTO for their “hardware” division (that’s all Sun Microsystems was to them, nothing more than a place to run Oracle’s RDBMS workloads). So that’s how my time at Sun ended. Not with a new product launch, but with a cardboard box and a severance letter, and a chunk of money that got instantly eaten up in the divorce process. As I cleared my stuff out of the Coventry office on my final, final day, I stumbled across a letter of complaint from senior execs at Capgemini. They were furious about my review of their HMRC contract I’d done in 2003, where I’d proven several issues they were beholden to, not least how they’d bumped up the contract from £3B over ten years to £8B. Instead of taking it on the chin, they’d gone down the petty road: “Wayne isn’t qualified to make this report.”

Which was hilarious, given HMRC had paired me with Chris Loughran, Deloitte’s most senior technologist and their Technical Director (who’d set up their technology practice). Chris handled the politics while I dealt with the technology and the critical analysis. I was qualified where it mattered. I’ve still got that letter, framed. A bunch of managerial no-hopers telling me I wasn’t qualified. People who couldn’t assemble a desktop PC, let alone architect a national-scale system. It still makes me smile. That report is a story for another day.

What Remained

Losing Sun hurt, but not everything was lost.

- The philosophy. “The Network is the Computer” still frames how I think about systems today.

- The craft. Measure first. Design for failure. Avoid clever hacks. Build boring, robust systems that survive.

- The people. The way Sun engineers thought and solved problems still defines what I consider “good” work.

- The mess. The understanding that real work happens in the mess. In the fragile, overloaded, unglamorous systems that can’t fail because too much depends on them. That’s where I always felt most at home.

- The contrarianism. Sun-backed engineers who thought differently, who argued, who didn’t fit the mould. That culture of contrarianism, of supporting diversity of thought, gave space for neurodiverse people like me to thrive. Asperger’s, autism, freaks, misfits, whatever label you want, Sun made room for it. They valued it. They knew that innovation doesn’t come from conformity. As my son Andy (also neurodiverse, sorry kids) puts it: “They need people like us to help solve these problems, because we have the imagination to try anything”. That was Sun.

Conclusion

Sun Microsystems was the best job I ever had, until Oracle dismantled it. It gave me a philosophy, a career, and a community of engineers who cared about the craft.

Those nine years confirmed who I am: someone who thrives in the middle of broken systems, where the work is hard and necessary. That’s what Sun gave me. And though I left under the shadow of the “sick antelopes,” I carried with me the only truth that’s ever really mattered: the network is the computer.

And I’ll say it again: Sun under Scott McNealy was an amazing company. Chaotic, brilliant, inspiring. He led like an ice hockey captain going into war.

And you know what? It was fucking great.

Scott McNealy: Oh Captain! My Captain!