This final essay completes a trilogy on power by asking what remains once its mechanics are fully understood. Building on Pfeffer’s organisational realism and Machiavelli’s historical clarity, it argues that unsanitised descriptions of power do not endorse cruelty but remove the moral alibis that allow harm to persist. By collapsing the distance between action and consequence, such writing makes innocence unavailable and neutrality impossible. The central risk, that truth can be weaponised, is acknowledged, but silence is shown to be more partisan, concentrating power through ignorance rather than constraining it.

Contents

- Contents

- 1. Introduction: The Moment Innocence Ends

- 2. The Function of Unsanitised Description

- 2. Machiavelli Is Not Inventing Cruelty

- 3. Removing the Moral Alibi

- 4. The Modern Parallel: Organisational Harm Is Not Accidental

- 5. The Hard Objection: Should Dangerous Truths Be Told?

- 6. Why Silence Is Not Neutral

- 7. After Knowledge, Neutrality Collapses

- 8. Conclusion: What This Kind of Writing Actually Demands

1. Introduction: The Moment Innocence Ends

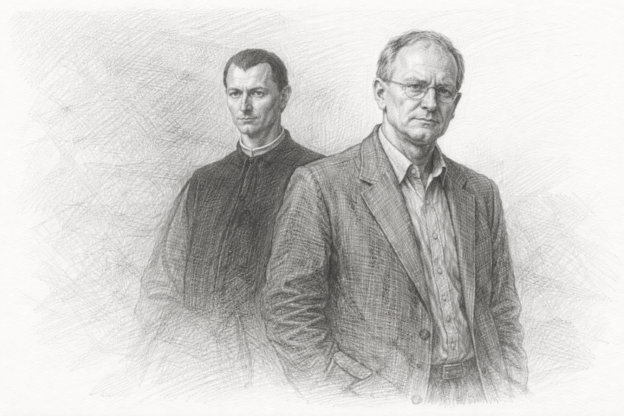

Some texts do not argue; they implicate. They do not persuade the reader toward virtue but strip away the excuses that made moral comfort possible in the first place. Once read, they leave behind a residue: knowledge that cannot be disowned. The Prince is such a text. So is Jeffrey Pfeffer’s work on organisational power. Both have been condemned as cynical, immoral, or dangerous. Yet the real threat they pose is not that they teach cruelty, but that they make it impossible to pretend cruelty is accidental.

Please note: This knowledge is heavy… it has a cost… and choosing what to do with it is legitimately difficult.

2. The Function of Unsanitised Description

Power does not require encouragement. It requires cover. Most harm inside political and organisational systems occurs not through explicit malice, but through abstraction, processes, incentives, and norms that diffuse responsibility until no one feels accountable. Machiavelli violates this arrangement. He describes how power behaves when survival is at stake, without moral cushioning. Pfeffer does the same centuries later, documenting how influence accrues through perception, alliances, and control rather than merit. In both cases, description performs an ethical act by collapsing the distance between action and consequence.

2. Machiavelli Is Not Inventing Cruelty

Nothing in The Prince would have surprised its intended audience. Renaissance Italy was not naïve about violence, betrayal, or ambition. Machiavelli’s princes are paranoid, strategic, and unstable because that is how fragile authority behaves. Cruelty must be measured. Fear must be managed. Appearances must compensate for insecurity. Read closely, the text reads less like endorsement than exposure: a catalogue of failure modes as much as tactics. To accuse Machiavelli of promoting brutality is to mistake anatomical clarity for admiration.

3. Removing the Moral Alibi

What Machiavelli refuses to provide, and what makes him intolerable, is a moral alibi. He does not pretend that good intentions govern political outcomes. He does not allow rulers to attribute violence to necessity without naming the choice involved. Pfeffer commits the same offence against modern organisations. By showing that careers advance through sponsorship, narrative control, and rule-bending, he eliminates the comforting fiction that outcomes are neutral. Once mechanisms are visible, claims of innocence collapse. Someone chose this structure. Someone benefits from it.

4. The Modern Parallel: Organisational Harm Is Not Accidental

Burnout, stress-related illness, exclusion, and quiet cruelty are routinely described as unfortunate side effects of complex systems. Pfeffer’s later work demolishes this evasion. These outcomes are predictable consequences of incentive designs that reward dominance, overwork, and silence. As with Machiavelli, the danger of Pfeffer’s work is not cynicism but causality. When cause and effect are made explicit, harm can no longer be dismissed as emergent or unintended. Denial becomes a decision.

5. The Hard Objection: Should Dangerous Truths Be Told?

The strongest counterargument is not moral outrage but caution. If describing power truthfully provides bad actors with a clearer playbook, does exposure make things worse? History offers reasons to worry. The Prince has been weaponised by authoritarians. Pfeffer’s rules can be read as justification for predatory behaviour. But this objection misunderstands where power already resides. Those inclined to abuse power do not require manuals; they already understand the terrain. What silence protects is asymmetry, where only incumbents and insiders grasp how the system actually works.

6. Why Silence Is Not Neutral

Withholding truth does not constrain power; it concentrates it. Sanitised narratives benefit those already positioned to exploit systems while leaving others disoriented and morally confused. The ethical risk of telling the truth is real, but it is unevenly distributed. Exposure removes plausible deniability from the powerful and orientation from the powerless only if it is withheld. Machiavelli and Pfeffer accept the danger of misuse because the alternative preserves ignorance as a governing principle—and ignorance is always partisan.

7. After Knowledge, Neutrality Collapses

Once power is understood, neutrality is no longer an option. The reader cannot retreat to claims of good faith or ignorance. This is the moment both texts force but do not narrate. Machiavelli does not tell the citizen what to do with the knowledge he provides. Pfeffer does not supply a moral programme sufficient to absolve the reader. What remains is responsibility. You either reproduce the system, attempt to reform it, or benefit quietly from its harms. All are choices. None is neutral.

8. Conclusion: What This Kind of Writing Actually Demands

Taken together, these three articles trace a progression. Pfeffer shows how power works. Machiavelli shows that this logic is not new. This final reckoning asks what is left once excuses are gone. The unsettling answer is accountability. To understand power and claim detachment is itself a position, one that aligns with the status quo while pretending otherwise. The most subversive act is not moral exhortation but clarity so sharp that cruelty can no longer hide behind ignorance, inevitability, or good intentions.