I own every appearance of Flaming Carrot, not as memorabilia but as a working instrument. This is a short essay about absurdity used with discipline: carrots against false seriousness, mockery as a tool, and what happens when you refuse to let power keep its costume. Flaming Carrot isn’t just a forgotten indie gem; he’s symbolic weaponry. Pataphysics writ large.

There are people who collect things quietly. Coins. Wines. First editions they never open. Their collections sit politely on shelves, murmuring value rather than intent.

Then there are the rest of us.

I have a full set of every appearance of Flaming Carrot, the comics, the cameos, the strange corners of continuity where he wanders in, does something inexplicable, and wanders back out again. And I don’t keep them as artefacts. I keep them as tools. A bit like Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies” Cards.

Because Flaming Carrot was never meant to be respected in the museum sense. He was meant to be deployed.

Absurdity as a Discipline

If you’ve never encountered Flaming Carrot, let me save you the trouble of a clean introduction: he wears a carrot on his head, fights surreal threats, and exists in a universe where logic has been mugged in an alley and left for dead. He is not parody in the cheap sense, nor is he random for randomness’ sake.

Flaming Carrot is disciplined absurdity.

Bob Burden’s work is chaotic only if you expect meaning to behave itself. If you read it carefully, what you find instead is a critique of seriousness itself—especially the kind of seriousness that insists on being taken seriously while saying nothing.

That’s why the collection matters.

Owning the Whole Argument

A “full set” isn’t about completeness for its own sake. It’s about context. About knowing when a thing is being sincere, when it’s lying, and when it’s mocking the idea that sincerity was ever on the table.

When Flaming Carrot shows up briefly in someone else’s comic, it’s rarely accidental. Those appearances are commentary. Easter eggs with teeth. Signals sent to readers who know how to look sideways at a story instead of straight on.

Owning the full run means owning the entire argument—not just the punchlines, but the long, strange conversation about heroism, masculinity, genre, and nonsense that runs underneath.

That’s power. Or at least, leverage.

Why This Still Matters

We live in an age that confuses confidence with clarity and volume with truth. Everyone has a brand. Everyone has a take. Everyone is deadly serious about things that dissolve under even mild scrutiny.

Flaming Carrot is a reminder that coherence is not the same as correctness, and that absurdity can be a form of honesty when straight talk becomes performative.

Sometimes, the most accurate response to a system is to wear a carrot on your head and refuse to explain yourself.

The Hitler’s Boot Issue

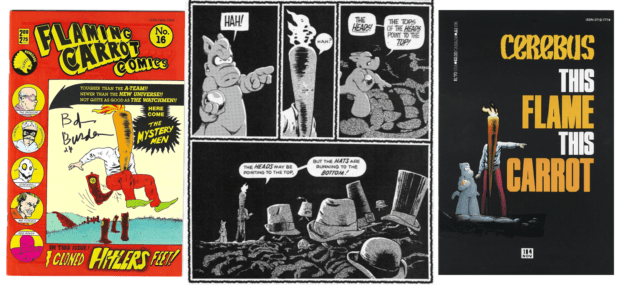

Flaming Carrot Comics #16, “I Cloned Hitler’s Feet” (Dark Horse Comics, June 1, 1987), is where the explanation finally collapses.

The title is not a misdirection. It is the point.

Burden takes one of history’s most over-mythologised figures and reduces him to a biological afterthought—boots, feet, fragments—stripped of grandeur and narrative authority. There is no confrontation here, no symbolic reckoning. Just the refusal to let evil retain aesthetic weight.

This is Flaming Carrot at his sharpest: absurdity used not as comedy, but as demolition. By making the unspeakable ridiculous, the work denies it the seriousness it depends on.

It’s not provocation for shock’s sake. It’s a reminder that mockery can be a moral act when reverence becomes dangerous.

Reductio ad Hitlerum, written large and imploding into nothingness.

This Flame, This Carrot

In Cerebus #104 – “This Flame, This Carrot”, Flaming Carrot appears not as a crossover stunt, but as a structural anomaly.

Set on the Highway 61 tower to the moon, the issue already exists outside stable reality. Flaming Carrot’s role is simply to be there… silent, pointing, uninterested in explanation. He does not belong to Cerebus’ cosmology, and he does not attempt to.

That’s the point.

His presence proves that even the most self-contained narrative systems can be punctured by something that refuses to participate on their terms. Flaming Carrot doesn’t integrate. He destabilises.

It’s a cameo that functions as a warning: coherence is not the same as completeness.

Mystery Men

The 1999 film Mystery Men translates Flaming Carrot’s sensibility into a form Hollywood could almost tolerate.

Based on Bob Burden’s comics, the film keeps the core idea intact: heroism as symbolic, incompetent, and deeply strange. These are not ironic failures or secret geniuses. They are people committed to absurd identities and operating without assurance that it will work.

The result is uneven, occasionally compromised, and unmistakably Flaming Carrot in spirit.

Mystery Men didn’t make absurdist heroism mainstream, but it left a residue. Many later deconstructions succeed because this one failed loudly first.

Flaming Carrot didn’t need the spotlight. He just needed to show it was movable.

Not Afraid to Use It

I don’t bring up Flaming Carrot to show off. I bring him up when conversations calcify. When frameworks become dogma. When someone insists that there is only one reasonable way to see the world.

Because nothing punctures false inevitability like a well-timed reminder that the universe has always been stranger than our models for it.

And yes, occasionally that reminder comes in the form of a man in a carrot costume fighting conceptual villains with weapons that may or may not exist.

I have the full set.

I know where the bodies are buried.

And if necessary, I will absolutely use it.