This article explores how Cicero, Machiavelli, and Ivy Lee each used “the message” as a vehicle for power, persuasion, and public control. From Cicero’s moralised rhetoric to Machiavelli’s cunning optics to Ivy Lee’s media-savvy framing, it dissects how messaging intersects with ethics, audience, and intent. Their techniques still shape political campaigns, corporate comms, and crisis response today—proving that the message is never just about words, but always about influence.

Contents

- Contents

- 1. Introduction: What Is “The Message”?

- 2. Cicero: The Republican Message as Rhetorical Ideal

- 3. Machiavelli: The Message as Political Tool

- 4. Ivy Lee: The Message in the Age of Mass Media

- 5. The Intersection: Power, Audience, and Truth

- 6. Key Techniques and How They Still Apply

- 7. Conclusion: The Message Is Never Just the Words

1. Introduction: What Is “The Message”?

Messages shape movements, elect governments, rehabilitate war criminals, and sell soap. Whether spoken in the Roman Senate, whispered in a Florentine palace, or typed on a 20th-century press release, the message has always been a tool of influence—and often, control.

This article explores how Cicero, Machiavelli, and Ivy Lee each understood and weaponised the message. It’s not just a historical survey. It’s an excavation of how rhetorical authority intersects with power, morality, class, and the medium itself.

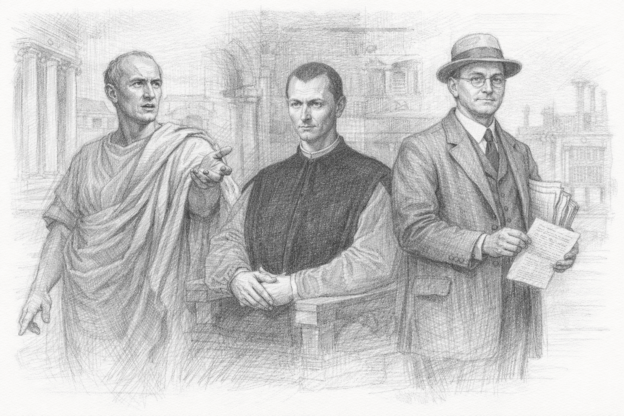

Together, these three figures form a strange but instructive triangle: Cicero the orator, Machiavelli the strategist, and Lee the modern fixer. The goal is not to praise or condemn, but to examine how their messaging philosophies still echo today—in politics, tech, media, and boardrooms.

2. Cicero: The Republican Message as Rhetorical Ideal

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC) was Rome’s most famous orator, a senator, a statesman, and a man ultimately executed for his words. For Cicero, the message wasn’t just communication—it was a form of political virtue. His works on rhetoric, such as De Oratore and De Re Publica, argue that persuasive speech is the cornerstone of civic life.

2.1 Cicero’s Messaging Philosophy

- Purpose: Persuade the educated citizenry through logos, ethos, and pathos.

- Medium: Speech and written argument—deliberate, formal, and performative.

- Power Structure: Republic-based; elite-led discourse meant to sustain civic order.

Cicero believed that rhetoric, if guided by philosophy and ethics, could shape the soul of a republic. But his belief in speech as a moral force was tested—and ultimately destroyed—by the rise of Caesarism.

“Nothing is so unbelievable that oratory cannot make it acceptable.”

Even Cicero, for all his virtue-signalling about the Republic, was a master of veiled attacks, coded barbs, and performative humility. The message, even for him, was theatre.

3. Machiavelli: The Message as Political Tool

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) was many things—civil servant, failed diplomat, torture survivor, and now, misquoted cynic. In The Prince, he writes not about good governance but about power maintenance. For Machiavelli, the message is what keeps you in office, not what keeps you virtuous.

3.1 Machiavelli’s Messaging Philosophy

- Purpose: Retain power through perception management.

- Medium: Diplomacy, rumour, policy, spectacle.

- Power Structure: Monarchic, top-down, dependent on illusion.

He understood that messaging isn’t about truth; it’s about utility. If the truth works, use it. If not, fabricate.

“It is not essential that a prince should have all the good qualities, but it is most essential that he should appear to have them.”

What Cicero did with high rhetoric, Machiavelli inverted into political optics. He acknowledged that the public would rather believe in the illusion of stability than the messiness of governance.

In modern terms, Machiavelli would be a strategist, not a spokesperson.

4. Ivy Lee: The Message in the Age of Mass Media

Enter the 20th century. The audience has changed. The medium is faster. The public has more literacy, but less time. And into this world steps Ivy Ledbetter Lee, the man who industrialised the message.

In 1906, Ivy Lee created the first modern press release for the Pennsylvania Railroad after a deadly crash. His brilliance wasn’t honesty—it was framing. He told the story before anyone else could. He shaped it.

4.1 Ivy Lee’s Messaging Philosophy

- Purpose: Control public perception through prepared narratives.

- Medium: Newspapers, statements, staged access.

- Power Structure: Corporate; message serves the interests of capital.

Lee later worked for Rockefeller during the Ludlow Massacre and even advised firms with ties to Nazi Germany. Yet he also pushed what he called the “two-way street” approach to PR—arguing that firms should listen as well as speak.

“Tell the truth, because sooner or later the public will find out anyway. And if the public doesn’t like what you are doing, change your policies.”

Was it moral insight or self-preserving pragmatism? Probably both.

5. The Intersection: Power, Audience, and Truth

Across these three figures, the message intersects with power in different configurations:

| Figure | Message Function | Audience Role | Ethical Frame | Medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cicero | Civic persuasion | Active, educated | Rhetorical virtue | Oratory, letters |

| Machiavelli | Strategic survival | Gullible, emotional | Expedient deception | Policy, perception |

| Ivy Lee | Narrative framing | Passive, reactive | Truth as tactic | Media, press releases |

The message isn’t static. It’s shaped by:

- Who is speaking? (Senator, Prince, Spokesman)

- Who is listening? (Citizen, Court, Consumer)

- What’s at stake? (Virtue, Stability, Profit)

- How fast does it move? (Word of mouth, rumour, syndication)

6. Key Techniques and How They Still Apply

6.1 Cicero’s Rhetoric

- Technique: Align reason with emotion to move elite audiences.

- Modern Use: Legal argument, academic debate, longform journalism.

6.2 Machiavelli’s Realpolitik

- Technique: Use the appearance of virtue to mask intent.

- Modern Use: Political branding, CEO apologies, campaign strategy.

6.3 Ivy Lee’s Media Control:

- Technique: Own the narrative early. Frame it helpfully. Listen, then spin.

- Modern Use: Corporate comms, influencer reputation management, PR crisis control.

7. Conclusion: The Message Is Never Just the Words

In every age, the message is more than content. It is strategy, delivery, illusion, and power. Cicero dressed it in ethics. Machiavelli cloaked it in cunning. Ivy Lee sold it to the public as the truth.

Each believed they were serving their context. But each, in his way, helped shape the contexts we live in now.

So the next time you hear a polished statement, a televised apology, or a manifesto that feels too perfectly balanced, ask yourself:

Who benefits from this version of the truth?

And whose playbook are they using?