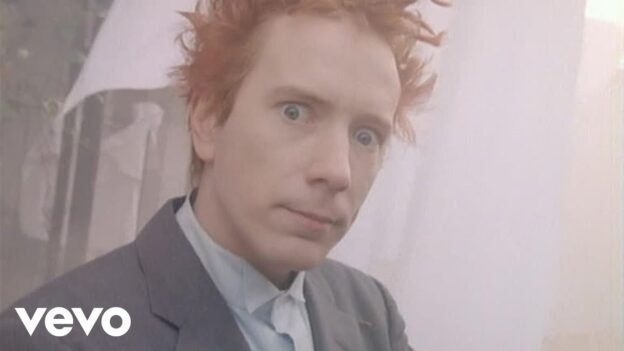

“Rise” by Public Image Ltd is not a song about hope or release. It is a manual for forward motion under pressure. Angular, repetitive, and unrelenting, it treats anger as usable energy rather than emotion. This track pairs with work done without validation, when opposition provides structure and refusal becomes propulsion.

Contents

1. Introduction

In Hellboy (2004), Karl Ruprecht Kroenen is described as having a terrible will. His body is dry, filled with sand, animated not by warmth or vitality but by sheer decision. He does not live in the way others live. He persists. He moves because stopping is not an option available to him.

That phrase — a terrible will — has stayed with me because it names something real.

What I have is not cinematic, not villainous, and not supernatural. It is the result of autism, Asperger’s traits, and trauma interacting over time. But the mechanism is recognisable: continuation without comfort, output without ease, delivery powered by something other than replenishment.

I deliver far beyond what most people can.

That is not virtue.

It is configuration.

2. The Absence of Ease

Many people deliver work, care, creativity, and leadership through systems that refill them: social affirmation, intuitive navigation of ambiguity, emotional reciprocity, a sense that the world notices and responds.

When you are autistic, that background ease is unreliable.

When you are traumatised, it may be absent altogether.

Instead of flow, there is friction.

Instead of assumption, there is calculation.

Instead of being carried, there is load-bearing.

You do not move because it feels good, or because it is seen, or because it is rewarded in the moment. You move because stopping introduces instability. You move because the work matters. You move because not delivering violates something internal and absolute.

That is will — but not the romantic kind.

3. A Dry Engine

Trauma dries things out. So does chronic misattunement. Over time, you learn not to rely on fuel that may not arrive. You learn to conserve. You learn to operate on minimal signal.

The result looks cold from the outside.

Focused.

Unyielding.

Excessively precise.

This is often misread as obsession, arrogance, or emotional distance. In reality, it is a system designed to function without reassurance. A mind that cannot assume support, so it builds scaffolding out of principle instead.

Pressure provides structure.

Opposition provides direction.

Remove both too quickly and coherence degrades before anything restorative has time to replace them.

This is why the will feels terrible — not because it is cruel, but because it is expensive.

4. Delivery Without Validation

For many people, validation means praise or agreement. For me, validation means engagement: being taken seriously, having thinking interacted with, used, carried forward.

When that engagement is absent, delivery does not stop, but the cost rises.

A terrible will does not stop when unseen.

It does not slow when misunderstood.

It does not wait to be met.

It delivers anyway.

In practice, this means output often continues long past the point where external incentives have disappeared. The work persists because stopping creates a different kind of failure — one that the system is not built to tolerate.

5. Anger as Energy

Some systems run on replenishment. Others run on resistance.

Anger and hate are not moral positions here; they are fuels. Directional. Compressing. Reliable. They narrow the field and generate torque. They keep the machine aligned when nothing else will.

I first encountered Rise in 1986 on No Limits, a late-night UK TV programme that fed music to people already wired for intensity rather than comfort. It landed not as rebellion, but as instruction.

Think Rise by Public Image Ltd, not catharsis, not hope, but propulsion. Forward motion driven by refusal.

There is also something personal embedded in it for me. Lydon is Anglo-Irish, and in the chorus he reaches for an old Irish blessing: “may the road rise with you”. The phrase you give a weary traveller setting out on something difficult: not comfort, not softness, just endurance. That lands differently when you share the same inheritance.

This is not pretty energy. It is effective energy.

And it explains why safety can feel destabilising: remove the opposing force too abruptly and the structure that depended on it begins to lose definition.

6. The Moral Weight of Will

There is a quiet ethics to this way of operating.

If clarity is rare, you treat it carefully.

If meaning is hard-won, you do not waste it.

If you know what it takes to keep going, you do not trivialise effort.

People with a terrible will become reliable not because they are resilient in a cheerful sense, but because they cannot tolerate internal incoherence. Saying you will do something and not doing it feels like internal collapse. Letting standards slide feels like self-erasure.

So you deliver.

Again and again.

7. Not a Superpower

This is not a superpower. It is an adaptation.

It can produce extraordinary output, but it is not free. Systems optimised for endurance under strain do not automatically reconfigure for ease. Transition, when it occurs, is non-trivial and rarely reversible on demand.

A terrible will is what remains when you have learned that no one is coming, and you decide that the work will exist anyway.

8. Conclusion: What It Takes

To deliver does not always take motivation, confidence, or inspiration.

Sometimes it takes:

- a refusal to abandon meaning

- a commitment that outlasts comfort

- a will that functions without nourishment

Dry.

Full of sand.

Still moving.

That is what it takes.