Birthgap and the Illusion of Choice: Why Population Collapse and Behavioural Sink Are the Same Crisis Seen from Different Scales. This article argues that modern societies face a dual crisis that only appears contradictory: demographic decline alongside rising social and psychological overload. Drawing on demographic research, behavioural-sink theory, and the Birthgap thesis, it shows how delayed parenthood and declining fertility coexist with intensified competition, urban stress, and digital saturation. The core mechanism is reproductive and social desynchronisation, which produces biologically emptier societies that nevertheless feel increasingly crowded. Together, these dynamics reveal a structural failure of modern social organisation rather than a matter of individual choice. The illusion of choice is that there is a choice.

Executive Summary (TL;DR)

Modern societies are caught in a hidden crisis: they feel psychologically overcrowded (intense competition, delayed life milestones, social saturation) while simultaneously undergoing demographic collapse (falling birth rates, ageing populations).

This isn’t two separate problems: it’s one mechanism seen from different angles.

The missing link is reproductive desynchronisation: life courses have stretched out (longer education, later careers, prolonged partner search), shifting parenthood into a narrower, later biological window. When everyone delays, coordination fails—many people never align in time to have children, even if they want them.

Rising childlessness (far more than shrinking family sizes) drives most of the fertility drop. The famous “behavioural sink” from Calhoun’s mouse experiments didn’t vanish; it migrated from spatial overcrowding to temporal overcrowding: too many options, too little shared timing.

Common fixes (cash incentives, automation, migration) fail because they don’t restore synchrony. Narratives that frame low fertility as empowered “choice” overlook the widespread unplanned childlessness and regret hidden beneath them.

Bottom line: we didn’t run out of space or consciously choose fewer kids… we ran out of shared time, and mistook structural timing failure for freedom. Unless societies redesign institutions to enable earlier viable adulthood, the decline becomes irreversible.

Contents

- Executive Summary (TL;DR)

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. BirthGap: The Video

- 3. The Paradox We Keep Missing

- 4. What Birthgap Claims… And Why It Matters

- 5. The Mainstream Counter-View (Steel-Manned)

- 6. Why The Counter-View Still Fails

- 7. Behavioural Sink, Reclaimed

- 8. Temporal Saturation And The Failure Of Catch-Up

- 9. Why Fixes Keep Failing

- 10. The Ideology Of “Choice”

- 11. What Would Actually Have To Change

- 12. Situating This Argument In The Broader Theory of Social Density

- 13. Conclusion: One Crisis, One Mechanism

1. Introduction

For decades, population debates have been framed as a choice between two competing anxieties. On one side, the fear of overpopulation: too many people, too few resources, ecological collapse. On the other, a newer concern: falling birth rates, ageing societies, labour shortages, and the slow hollowing-out of communities.

At first glance, these fears appear mutually exclusive. How can societies feel overcrowded, competitive, and socially saturated while simultaneously failing to reproduce themselves?

In the earlier article, “Conflicting Social Dynamics: Population Collapse Versus Behavioural Sink“, I argued that this contradiction is only apparent. Population collapse and behavioural-sink dynamics are not rival explanations. They are the same systemic failure, operating at different scales. One describes what happens to headcounts; the other describes what happens to behaviour under saturation.

The relatively recent documentary Birthgap adds an uncomfortable amount of empirical weight to this claim. But it also raises controversy. Its conclusions are disputed, its framing provocative, and its implications politically awkward. That makes it useful: not as an unquestioned authority, but as a stress test.

Even if Birthgap is only partially right, the dominant narratives about fertility, choice, and progress no longer survive contact with the data.

2. BirthGap: The Video

The documentary Birthgap assembles demographic data and cohort analysis to argue that fertility decline is driven primarily by rising childlessness rather than shrinking family size. Its framing is provocative and contested, but its emphasis on the timing of first births provides a useful empirical stress test for prevailing explanations.

3. The Paradox We Keep Missing

Across much of the developed world, fertility has remained below replacement level for decades. Schools close. Small towns wither. Pension systems strain under the weight of ageing populations. Entire regions become what might be called demographic “yesterlands”: fully built, fully inhabited, yet strangely empty of children.

At the same time, individuals report intense competition for jobs, housing, partners, and status. Urban life feels dense. Dating feels exhausting. Career paths stretch longer and longer. People delay everything — commitment, children, permanence — not because life is easy, but because it feels too full.

This is the paradox: societies are becoming biologically emptier while remaining psychologically overcrowded.

Traditional population thinking struggles with this because it measures numbers, not coordination. What matters is not how many people exist, but how tightly their lives are coupled in space, time, and social roles.

That is where Birthgap becomes relevant.

4. What Birthgap Claims… And Why It Matters

In its strongest form, Birthgap advances a destabilising claim: fertility decline is driven less by people choosing very small families and more by fewer people becoming parents at all.

Across multiple countries and decades, it argues that:

- Rising childlessness accounts for a large share of fertility decline.

- Family size among those who do become parents has changed less than commonly assumed.

- Delayed first births sharply increase the probability of never having any children.

- Late “catch-up” births occur, but at insufficient scale to offset early delays.

- Major economic and social shocks coincide with sharp, lasting drops in first births.

If taken at face value, this reframes the fertility debate. The problem is not simply how many children people want, but whether they ever cross the threshold into parenthood.

These claims are contested — and they should be.

5. The Mainstream Counter-View (Steel-Manned)

Most contemporary demography offers a more incremental account:

- Fertility decline reflects deliberate shifts toward smaller families.

- Education, urbanisation, female labour-force participation, and contraception increase opportunity costs.

- Ideal family size has fallen modestly in many cohorts.

- Global population is still growing and is projected to peak later this century before a gradual decline.

- Density and urbanisation are associated with innovation and resilience, not inevitable dysfunction.

From this perspective, low fertility is not collapse but transition. Behavioural-sink analogies are viewed as overextensions from artificial animal experiments.

If this account is sufficient, the paradox dissolves.

The difficulty is that it explains intentions far better than outcomes.

6. Why The Counter-View Still Fails

Preferences explain ideals; they do not explain why realised fertility systematically lags them.

Across Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, completed fertility remains consistently below stated intentions by roughly 0.3–0.5 children per woman. This gap is not trivial, and it is not evenly distributed. It concentrates heavily among those who never have a first child.

Even where intended family size has declined, many childless adults report having wanted children at some point. Over time, intentions adjust downward — often as a rationalisation of constraints already encountered. Adaptation is not the same as choice.

Reproduction is not an individual consumer decision. It is a coordination problem involving at least two people, constrained by biology, timing, and social synchrony. Preferences alone cannot determine outcomes when coordination fails.

Importantly, these mechanisms operate at multiple points. Delayed parenthood increases childlessness and reduces progression to second and third births. Smaller families and rising childlessness are not competing explanations — they are cumulative effects of the same desynchronised system.

Even a society aiming for 1.7 children per woman will experience demographic contraction if first births are delayed and dispersed. Without synchrony, intention becomes irrelevant.

This is the contribution Birthgap usefully forces into view, regardless of whether its framing is overstated.

7. Behavioural Sink, Reclaimed

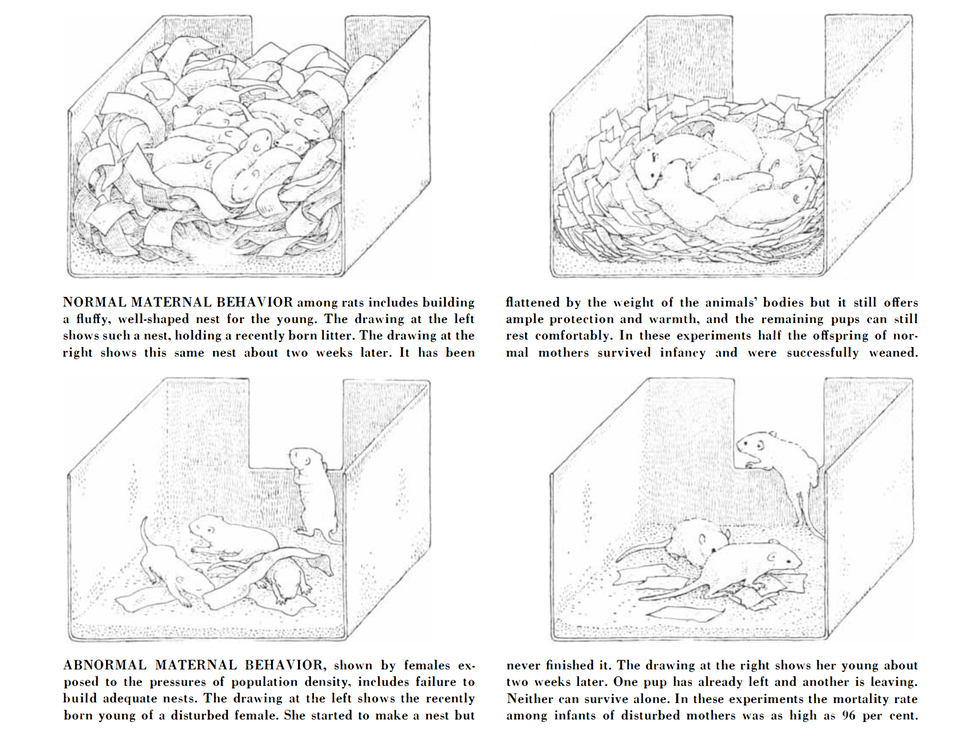

John Calhoun’s mouse experiments are often — and rightly — caricatured. Humans are not rodents. Cities are not cages. Physical density alone does not cause collapse; in many contexts it enables creativity and growth.

But Calhoun’s deeper insight was never about headcount. It was about role saturation and coordination failure under constrained systems.

Reframed for modern societies:

| Calhoun’s utopia | Modern society |

|---|---|

| Physical overcrowding | Life-course overcrowding |

| Role collapse | Extended adolescence |

| Withdrawal | Non-decision |

| Aggression | Mate competition, burnout |

| Social breakdown | Delayed family formation |

The mechanism has not disappeared. The axis has shifted.

The behavioural sink has moved upstream — from crowded space into crowded time.

8. Temporal Saturation And The Failure Of Catch-Up

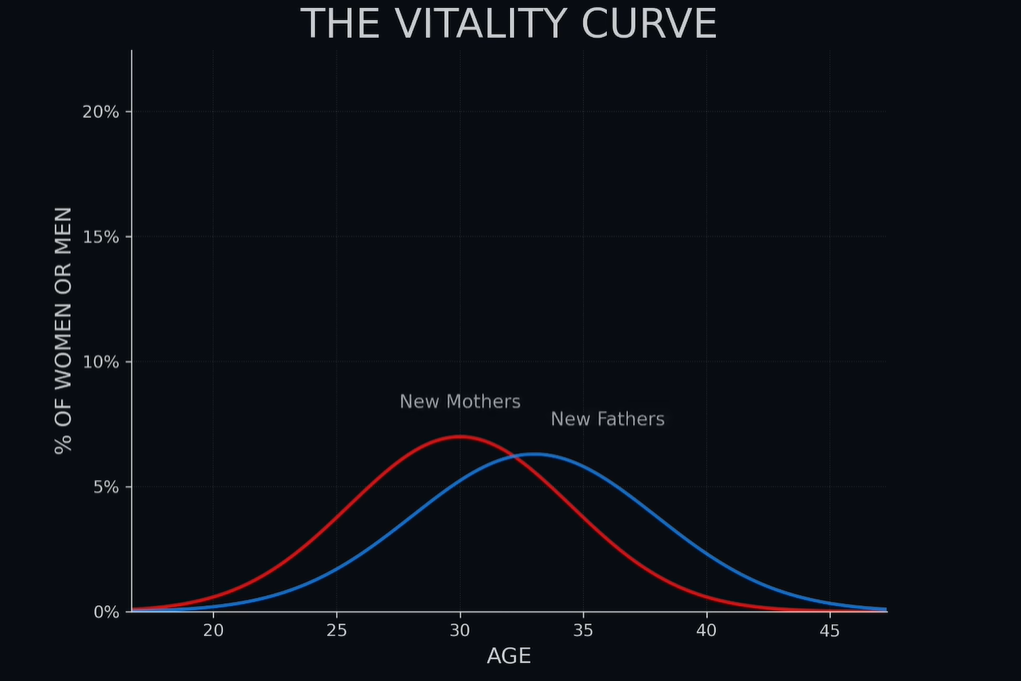

In theory, delaying parenthood should simply compress reproduction later. In practice, it does not.

Fertility declines non-linearly. Partner availability declines with age. Life trajectories diverge rather than reconverge. Assisted reproductive technologies extend the tail but do not change the underlying distribution.

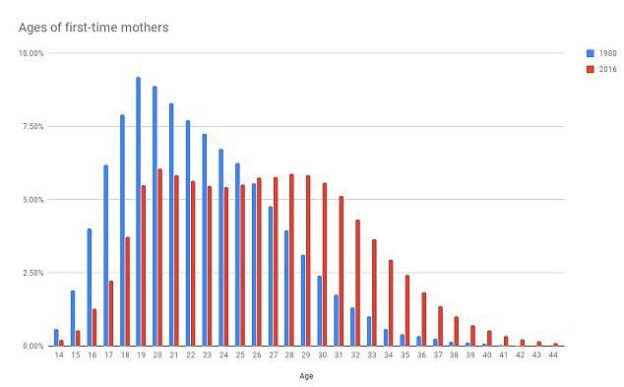

Demographic data consistently show a rightward shift in age at first birth — from the early-20s to the late-20s or early-30s — accompanied by a steep post-peak drop-off and limited late recovery.

This is not moral judgement. It is arithmetic.

When everyone waits, many never start.

That is behavioural sink expressed temporally: too many options, too little overlap, too few shared moments of readiness.

9. Why Fixes Keep Failing

Pronatalist incentives fail because they treat fertility as a cost problem rather than a coordination problem. Automation fails because robots do not reproduce, pay taxes, or provide care. Migration mitigates decline in receiving countries while exporting it elsewhere, hollowing out sending societies.

Each assumes reproduction responds primarily to inputs. It does not, once synchrony is lost.

10. The Ideology Of “Choice”

Low fertility is often framed as empowerment and progress. Environmental narratives cast fewer births as virtue. Liberal individualism interprets outcomes as preference. Certain strands of feminism treat demographic decline as liberation from constraint.

These narratives persist because they are morally comfortable. They convert structural failure into personal freedom.

But they rely on a silence: the silence of unplanned childlessness.

Childless adults rarely form political blocs. Regret is socially taboo. Loss without an identifiable event is difficult to articulate. As a result, the costs of desynchronisation remain largely invisible, while its supposed benefits are loudly affirmed.

This is not bad faith. It is an ideological blind spot.

11. What Would Actually Have To Change

If the problem is desynchronisation, then no amount of money, technology, or rhetoric will fix it unless societies redesign around earlier, more viable life-course alignment.

This does not mean coercion. It does not mean nostalgia. It does not mean reversing women’s rights.

It does mean confronting the reality that modern liberal societies optimise individual trajectory maximisation — prolonged education, delayed economic independence, late partnership — and then act surprised when collective reproduction fails.

Earlier economic autonomy. Shorter education bottlenecks. Normalising parenthood in the 20s as compatible with ambition rather than a derailment. Acceptance of imperfect timing.

In short: rebuilding around the young, not endlessly retrofitting systems for the old.

12. Situating This Argument In The Broader Theory of Social Density

In Conflicting Social Dynamics: Population Collapse Versus Behavioural Sink, I argued that modern societies face a dual crisis of social density that is widely misunderstood because it is framed along a single axis. Population collapse and behavioural-sink dynamics are typically treated as competing explanations for social dysfunction, when in fact they operate on different dimensions of the same system. One concerns biological continuity across generations; the other concerns lived experience under conditions of functional overcrowding. The paradox dissolves once we recognise that a society can be demographically emptying while simultaneously becoming psychosocially saturated.

Together, these two analyses illustrate a fuller picture of the dual crisis of modern social density: a world becoming biologically emptier yet psychosocially more strained (Horkan).

The present argument does not replace that framework; it sharpens and extends it. Where the earlier article mapped the structural contradiction — underpopulation at the macro level coexisting with overcrowding at the experiential level — this analysis focuses on the mechanism through which the two dynamics lock together. In particular, it shows how behavioural-sink-like saturation migrates upstream into time: into delayed adulthood, extended education, prolonged partner search, and deferred commitment. The result is not merely fewer children, but fewer people ever becoming parents at all.

Several themes from the original article are therefore strengthened rather than revised:

- Functional density over headcount: The argument that crowding is social, competitive, and informational — not purely spatial — is reinforced by showing how coordination failure, not scarcity, constrains reproduction.

- Mutual reinforcement: Population decline and behavioural-sink pressures are not independent trends; desynchronised life courses translate psychosocial overload directly into demographic contraction.

- Technological and institutional misalignment: Digital saturation, career signalling, and legacy institutions amplify both psychosocial strain and reproductive delay, tightening the feedback loop identified earlier.

- The illusion of choice: What appears as voluntary fertility decline increasingly reflects structural timing failures — a point implicit in the original framework and made explicit here.

Read together, the two pieces describe a single system seen from different angles. The first establishes what kind of society we have become; the second explains why that society fails to reproduce itself. The conclusion is not that modernity chose decline, but that it unintentionally engineered conditions in which social saturation and biological contraction reinforce one another, leaving societies simultaneously overwhelmed and unsustained.

13. Conclusion: One Crisis, One Mechanism

We did not run out of space.

We did not consciously choose extinction.

We ran out of shared time — and mistook the result for freedom.

Population decline is not the opposite of behavioural sink. It is its demographic shadow. The sink did not disappear; it migrated upstream, into crowded lives rather than crowded cities.

Until that is acknowledged, societies will continue debating preferences while quietly losing the capacity to reproduce themselves.

And by the time the numbers make the problem undeniable, the window for synchronisation will already have closed.

The illusion of choice is that there is a choice.