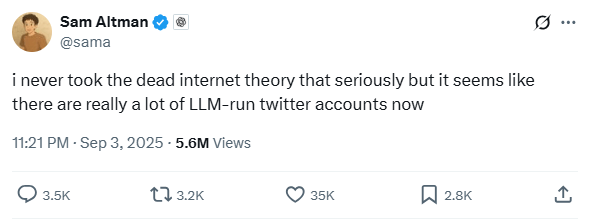

Every few years the internet collectively rediscovers an old conspiracy theory. This month it has been the so-called “Dead Internet Theory”. The idea, put simply, is that most of what we now encounter online is no longer produced by humans but by bots, scripts, and automated systems. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, recently hinted that he thought there might be something in it, which was enough to trigger a storm of hot takes across Twitter. So what exactly does this “death” mean, and is there anything to it?

I should say that I’ve written about this before in my More Bollocks series, in a piece called More Death of the Internet Bollocks: A Satirical Look at the Hysteria Around “The End”. That one was inspired, bizarrely, by a conversation with my long-term friend and our social media manager, Robert Hall, who is an absolutely lovely guy. The point then, as now, was that while the theory makes a lot of noise, most of it doesn’t stand up when you look more closely.

The “Dead Internet Theory”: An Internet Ghost Story

The argument is that the internet we see today is a ghost of what it once was. The original promise of free expression, decentralisation, and grassroots publishing has given way to centralised platforms. Much of what you read, click, or even argue with on the big platforms could be machine-generated. Engagement metrics rather than human community drive the content you see. The fear is that the internet has become a synthetic simulacrum, sustained by bots that mimic human behaviour and churn out material at scale.

It Must Be True

Supporters point to a few obvious signs:

- Bots everywhere. Search engine crawlers, spam accounts, click farms, SEO manipulation tools. In some spaces they outnumber people.

- Content farms and AI writers. The flood of machine-generated text, video, and images makes it harder to know what is authentic.

- Manipulation at scale. State-sponsored troll factories and coordinated disinformation campaigns operate continuously.

- The decline of the “wild west” web. Independent forums, blogs, and quirky personal sites are harder to find. Instead, we swim in a sea of algorithmically amplified sameness.

Taken together, these trends suggest an internet where authentic human presence is the minority.

Total Codswallup

But to declare the internet “dead” is a little glib.

- Humans are still here. Every botnet, every automated system, is built, operated, or at least guided by people. Even the worst click farm exists to exploit human curiosity.

- Automation is not new. As far back as the late 1990s, bots were a feature not a bug. My own small example was a tool I built nearly twenty years ago called Blog Ping Jar, which forced search engines to index sites faster and improved SEO dramatically. That was a robot doing work, but in service of human publishing.

- Evolution not death. Tim Berners-Lee, the Englishman who invented the web, imagined stages: first linked documents, then linked data, then the semantic web, and eventually agent-based systems. In that sense, bots and AI agents were always part of the roadmap.

- Resilient diversity. For all the noise, the internet still contains a staggering variety of voices. It may feel more sanitised, but it remains both richer and broader than any pre-internet medium.

Everyone Has An Opinion, Even Me

I never really believed the internet was a purely human space. From the start it was also a place for machines. Google itself is nothing more than a vast automated index of our output, ranking and ranking again. At Cyber Tzar we see about 250 bot login attempts every ten minutes, roughly half from China and half from Russia. Some are malicious, most are just noise. Bots are not an aberration. They are the environment.

What has changed is the balance. The “wild west” spirit has ebbed away. Instead of stumbling across the weird and wonderful, we are shepherded into corporate platforms, nudged along by recommendation engines, and asked to behave. It is your mum and dad’s internet now, mediated by artificial intelligence. That feels different, but not quite the same thing as “death”.

If anything, the internet today is what its inventors anticipated. Machines and humans sharing the same network, sometimes collaborating, sometimes clashing. It is messy, compromised, and often irritating, but it is still alive.

Where This Leaves Us

I was discussing this recently with an old friend, Ian Dunmore, who made his name with the influential site Public Sector Forums. We agreed that what matters now is how we adapt to this new balance of human and machine. That deserves a fuller piece in its own right, so I will follow up with a second article looking at the internet’s continuing transformation and what it means for trust, authenticity, and community.

In fact, Ian and I were debating this only the other night. He argued thoughtfully, as he always does, that much of today’s internet feels “polished but hollow”, echoing writers like Meghan O’Rourke and François Chollet who worry about a flattening of expression into algorithmically optimised outputs. I was more blunt, pointing out that humans have always generated plenty of rubbish too:

“AI can polish the turd so you’ve read it before you go that was shite. I think that might be the issue, the waste of time assessing merit.”

That exchange captured our different registers — Ian deliberate and philosophical, me more direct and pragmatic. Yet we both came to the same conclusion: what’s at stake is not whether the internet is alive or dead, but how we recognise value in a space increasingly crowded by noise, automation, and regulatory walls.

Flags, Firewalls, Control, and Sovereignty

The wider backdrop to these conversations is the raft of cloud sovereignty debates now taking place. SAP, for instance, recently announced £50m to support European cloud sovereignty. That grabbed attention, but it is hardly new. I argued back in 2009 that the UK needed its own sovereign cloud infrastructure to protect national interests. At the time this was largely shouted down as alarmist, but the concern was straightforward: what happens when sensitive data, particularly government systems, are hosted offshore?

That concern was vindicated a few years later when I worked at the Home Office and helped redesign border control systems. Senior colleagues put it bluntly: “at least here, if something goes wrong, we can call the police and they’ll turn up”. That clarity of control contrasted with today’s wave of country-based sovereignty initiatives, which feel, if anything, slightly out of date. They are emerging at the same moment as the rise of demagogues — Putin, Xi, Erdoğan, Trump, Farage, even Corbyn in his way — and reflect an undercurrent of populism tied to flag, territory, and control. The outcome risks a balkanised internet, fragmented into walled gardens, easier for states to monitor, shape, and restrict, just as we already see in China and Russia.

For Ian and me, this is where all the threads join: bots, AI content, sovereignty, the lost “wild west” spirit of the internet, hyperreality, semiotics, and the regulatory drive to contain what was once borderless. It is a fascinating and troubling mix.

This will set up my follow-up article about Ian, Public Sector Forums, and our early adventures together, including the time I was briefly sacked from my dream job as CTO for the UK and Ireland at Sun Microsystems after an interview I did with Ian for PSF, a moment that says a lot about his sharp eye for the issues and the impact that community created.

References

- Sam Altman on Twitter

- Wikipedia: Dead Internet Theory

- Forbes: Sam Altman is Starting to See the Dead Internet Theory