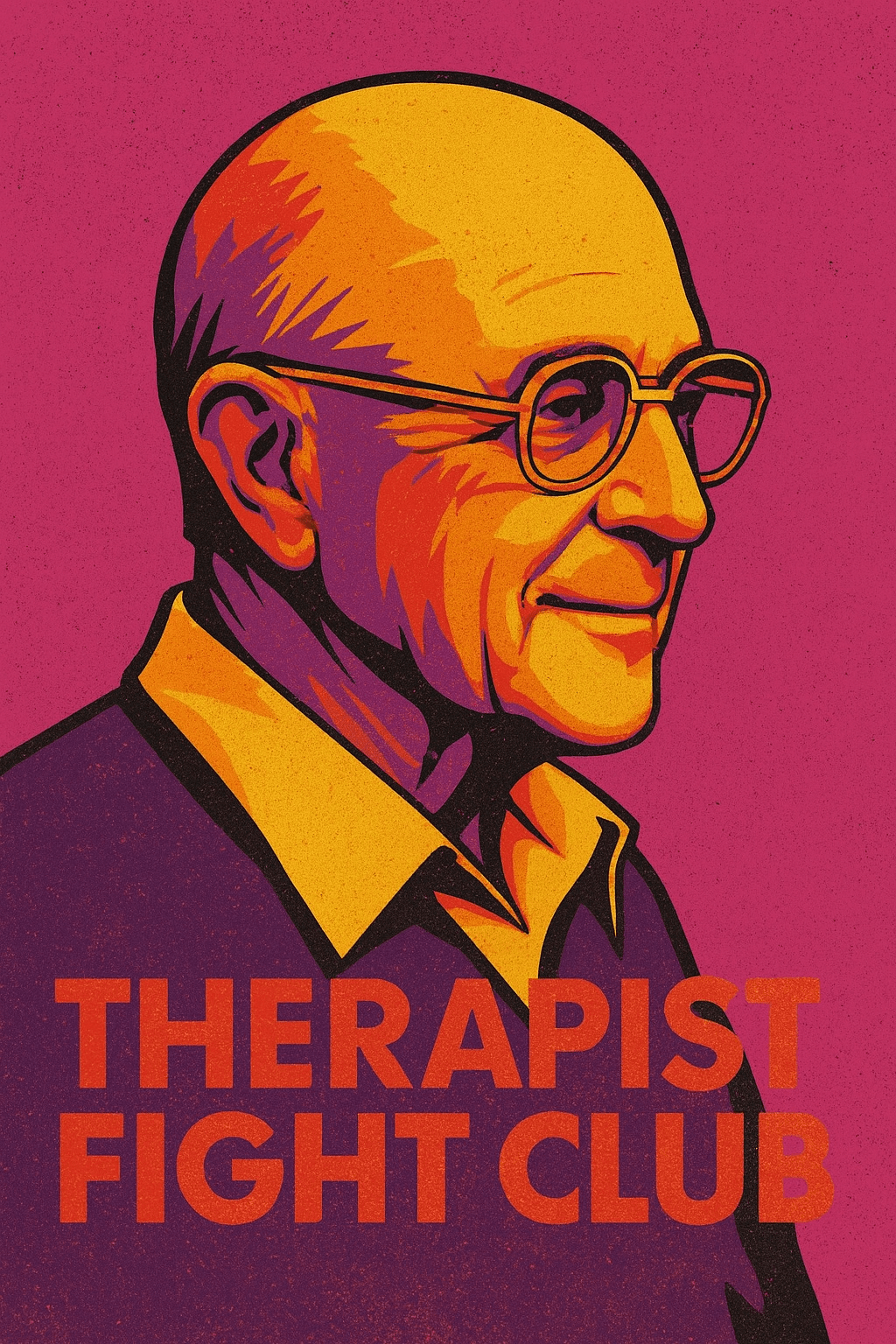

This article reinterprets Carl Rogers’ person-centred psychology through the lens of Asperger’s and systems thinking. Stripping away sentimental language, it presents Rogers’ model as a structured feedback loop, a “Therapist Fight Club” where both therapist and client co-train, honing coherence and self-consistency. Written as an interest piece for the neurodiverse, it reframes therapy not as emotional fixing, but as optimising a system to run with fewer contradictions.

When people talk about therapy, it often sounds abstract, emotional, and uncomfortably human-centred. For someone on the autism spectrum, particularly with Asperger’s, this can feel confusing, even irrelevant. After all, with eight billion people on the planet, why should “understanding humans” carry so much weight?

But if you strip away the soft language and view psychology as a kind of system optimisation, Carl Rogers’ approach, known as person-centred psychology, becomes far more accessible. It’s less about being “touchy-feely” and more about creating conditions where any individual system (you) can stabilise and run more efficiently.

This article was inspired by my friend Sonia, who runs a person-centred encounter group for therapists. Her work creates a space where practitioners can hone their skills, share experiences, and refine the very conditions Rogers described: empathy, authenticity, and acceptance, making them sharper and more effective in their practice. I joked that it sounded kind of like “Therapist Fight Club”, and ergo sum, that thought became the spark for this article.

The Core of Rogers’ Model

Carl Rogers (1902–1987) was a psychologist who flipped the traditional idea of therapy on its head. Instead of the therapist being the expert who diagnoses and directs, Rogers argued that:

- Every individual already has the capacity to grow and self-correct.

- Problems arise when the environment interferes with that natural process.

- The therapist’s role is to create the right environment, not to impose solutions.

Think of it like running a program: most code runs fine, but in the wrong operating conditions it throws errors. Rogers wasn’t rewriting the code; he was stabilising the environment so the code could execute as intended.

The Three Core Conditions (the “Rules of the Training Environment”)

Rogers believed that for growth to happen, three conditions must be present:

- Unconditional Positive Regard

- The therapist accepts you fully, no matter what you say.

- This doesn’t mean approval — it means no judgemental rejection.

- Analogy: a debugging session where no line of code is dismissed outright.

- Empathy

- The therapist tries to see the world from your perspective.

- Not sympathy, not “feeling sorry for you.” Just perspective-taking.

- Analogy: understanding why a program outputs a certain result, given its inputs and logic.

- Congruence (Genuineness)

- The therapist is honest and real, not hiding behind scripts.

- Analogy: a dataset without corrupted labels — reliable, trustworthy input.

Together, these three conditions create a low-noise test environment where the client can experiment, reflect, and adjust without penalty.

Person-Centred Therapy as a Feedback Loop

For people who prefer systems thinking, it helps to view Rogers’ therapy as a training loop:

- Client = adaptive model

Inputs = experiences, thoughts, behaviours.

Outputs = words, emotions, self-descriptions.

Goal = reduce misalignment between self-concept (who you think you are) and experience (how life actually plays out). - Therapist = training environment

Inputs = client’s outputs.

Outputs = acceptance, empathy, honest feedback.

Goal = provide stable conditions so the client system can converge on a coherent self-concept. - Interaction = iterative loop

Each session is like another training epoch. The client updates internal weights (beliefs, behaviours), while the therapist fine-tunes their empathic accuracy.

This makes therapy less about “healing emotions” and more about reducing internal contradiction — something a logical mind can appreciate.

The Therapist’s Gain (and Why It Can Look One-Sided)

From a detached perspective, you might notice: this looks more valuable for the therapist than the client.

- Therapists constantly train themselves to be better at empathy, acceptance, and congruence. Every new client is fresh data.

- Clients, by contrast, may or may not engage deeply enough to benefit.

So the therapist’s curve of improvement is guaranteed, while the client’s benefit is conditional. In other words, person-centred therapy upgrades the trainer as much as the model.

But the potential client gain is real:

- A rare environment where ideas can be tested without punishment.

- A mirror that reflects your logic back more clearly than you might perceive yourself.

- Consistent, honest feedback with low noise.

Why It Matters for People with Asperger’s

If you have Asperger’s, you may often experience:

- Friction between your self-concept (“I am logical, efficient, detached”) and society’s expectations (“You should be warm, social, emotionally expressive”).

- Confusion about social rules, which can feel like corrupted input data.

- Fatigue from masking or trying to fit in inconsistent environments.

Rogers’ approach doesn’t demand that you change your wiring. Instead, it provides a sandbox where you can process experiences, experiment with new approaches, and stabilise your sense of self without pressure to perform.

The “Therapist Fight Club” Metaphor

Why call it “Therapist Fight Club”?

Because Rogers’ method is less about the surface drama of therapy and more about the underground, stripped-down rules of engagement that both therapist and client follow. Like in Fight Club, there are hidden rules that govern the arena:

- You are accepted here.

- You will be understood from your perspective.

- No fake fronts are allowed.

This framework makes therapy less about “feelings” and more about a structured contest against self-inconsistency. Both therapist and client are sparring partners in a feedback loop, learning from each other, improving with each round.

Closing Thoughts

Carl Rogers’ person-centred psychology is often presented as warm, humanistic, and deeply emotional. For someone with Asperger’s, that framing may feel alien or unhelpful.

But reinterpreted as a system of iterative optimisation, it becomes something else entirely:

- A feedback environment designed to reduce contradictions.

- A training loop where therapist and client co-evolve.

- A framework where you are accepted not for being “normal,” but for being consistent with yourself.

In that sense, Rogers wasn’t trying to make you “more human” in the sentimental sense. He was trying to create conditions where your system could run with fewer bugs, and that’s an idea that resonates across neurotypes.