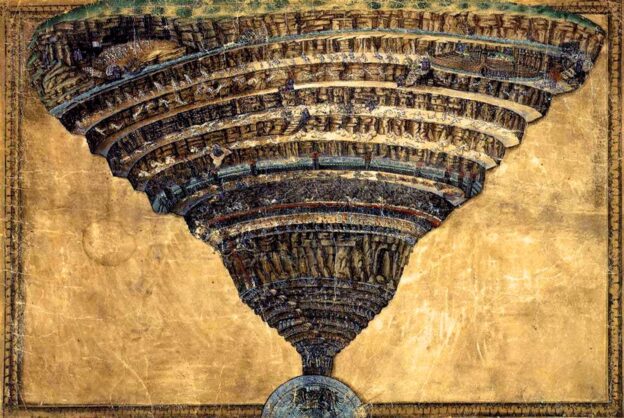

This article explores Dante’s Inferno as a structured moral and theological descent, examining the logic behind each of the nine circles of Hell. From lust and gluttony to fraud and treachery, each level reveals how Dante views sin not just as misdeed but as a deformation of the soul and will.

Introduction: Hell as Moral Cartography

Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, the first canticle of The Divine Comedy, offers more than just a vivid medieval vision of damnation, it is a meticulous moral architecture. Unlike the chaotic torment imagined in popular depictions of Hell, Dante’s version is structured with deliberate hierarchy. Its descending circles are organised not by the severity of pain alone, but by the quality of sin, grounded in Aristotelian ethics, Thomistic theology, and Roman jurisprudence. Each level functions as a theological diagnosis of the soul, a cosmological courtroom where justice is not arbitrary, but exact.

In this article, we descend, circle by circle, to explore how Dante constructs sin as disorder, how punishment reflects the internal nature of transgression, and how Hell ultimately mirrors the rationality of divine justice.

Circle I: Limbo, The Virtuous Unbaptised

Sin: Lack of baptism and explicit faith

Punishment: Eternal longing without torment

Limbo is populated by the great figures of antiquity: Homer, Horace, Socrates, and even the Muslim philosopher Averroes. These souls suffer no pain, only the sorrow of exclusion from God. Their punishment is the gentlest in Hell, reflecting Dante’s respect for wisdom and virtue outside Christianity, while still affirming the theological necessity of grace.

Circle II: The Lustful, Blown by Storms

Sin: Carnal desire overcoming reason

Punishment: Eternal battering by violent winds

Here we meet Francesca da Rimini, who speaks of love’s seductive power while swept in a storm symbolic of uncontrolled passion. This circle marks the beginning of punishments aligned with incontinentia, sins of excess where reason yields to appetite.

Circle III: The Gluttonous, Wallowing in Filth

Sin: Overindulgence in food and drink

Punishment: Lie in vile slush while pelted by icy rain, guarded by Cerberus

The gluttons, reduced to mouths and stomachs, now wallow in a disgusting, freezing mire. Their insatiability has left them inert, parodies of the Eucharistic banquet turned into grotesque consumption without community.

Circle IV: The Avaricious and the Prodigal, Colliding Souls

Sin: Misuse of wealth (hoarding or squandering)

Punishment: Roll heavy weights in eternal opposition

Guarded by the figure of Plutus, this circle reflects Dante’s nuanced view of material sin, not just greed, but mismanagement of God’s gifts. The hoarders and wasters crash against one another, locked in a meaningless cycle that mimics the economy stripped of purpose.

Circle V: The Wrathful and the Sullen, Choked by the Marsh

Sin: Unjustified anger (active and passive)

Punishment: Wrathful fight on the surface of the Styx; sullen gurgle beneath it

The wrathful express their fury through violence; the sullen internalise it in bitterness. Both forms of anger distort the soul, turning its energy inward or outward in futile rebellion. Here, Dante begins to deepen his psychological account of sin.

Circle VI: The Heretics, Burned in Flaming Tombs

Sin: Denial of immortality or divine truth

Punishment: Eternally entombed in fire

This is the first circle of Lower Hell, entered by crossing the river Styx. It is where the truly defiant begin. The flaming tombs symbolise the consequence of doctrinal pride and intellectual rebellion, the heretics are imprisoned within the false beliefs they once held, unable to see beyond their temporal arrogance.

CCircle VII: The Violent, Divided by Target

Sin: Violence against others, self, and God/nature

Punishment: Varies by subcircle, boiling blood, thorny woods, burning sand

This circle is divided into three rings, each reflecting a different kind of violence:

- Violence against others: Souls of murderers and tyrants are submerged in a river of boiling blood, guarded by centaurs who shoot arrows at those who try to rise above their allotted depth.

- Violence against self: The suicides are transformed into twisted, thorny trees in the “Wood of the Suicides.” Since they rejected their human bodies in life, they are denied them in death. Their only voice comes through pain: they can speak only when their limbs are broken.

- Violence against God, nature, and art: This ring houses blasphemers, sodomites, and usurers, all punished on a barren plain of burning sand beneath a rain of fire.

Among the suicides, Dante includes the profligates, souls who squandered their lives in reckless abandon. Though not suicides in the strict theological sense, they are punished in the same desolate wood. Hounded perpetually by black bitches, they are torn apart again and again, representing their manic waste of self and substance. Their inclusion suggests that not all destruction of the self comes through despair, some comes through disorderly indulgence, driven by ungoverned appetite.

This entire circle demonstrates Dante’s preoccupation with disruption of the natural order, whether through bloodshed, self-annihilation, or perversion of divine law. Each ring reflects a violence that tears at the very fabric of creation.

Circle VIII: Malebolge, The Fraudulent

Sin: Fraud against those not bound by trust

Punishment: Ten bolge (ditches), each with a tailored punishment

This is Dante’s most elaborate structure, a bureaucratic hellscape of liars, seducers, flatterers, simoniacs, soothsayers, corrupt politicians, hypocrites, thieves, false counsellors, sowers of discord, and counterfeiters. Each punishment reflects the nature of deceit: backwards-walking prophets, schismatics torn in two, flatterers sunk in excrement.

Fraud undermines the fabric of society and reason itself. This is sin with method, perversion of intellect, and for Dante, the most human of faculties.

Circle IX: Cocytus, The Traitors

Sin: Treachery against those bound by trust

Punishment: Frozen in ice, progressively more encased

Unlike the fiery hells of folklore, Dante’s deepest sin is punished with ice, the cold absence of love. Treachery violates the bonds that make civilisation possible. The four regions of Cocytus descend from traitors to kin (Caina), to country (Antenora), to guests (Ptolomea), and finally, to benefactors (Judecca).

At the very centre of Hell, Satan himself lies trapped in ice, his wings beating futilely, creating the frozen wind that chills all around him. He chews endlessly on Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius, betrayers of divine and imperial order.

Conclusion: Justice Made Visible

Dante’s Hell is not a theatre of gratuitous torment but a moral architecture of exacting precision. Each circle descends deeper into disorder, moving from sins of impulse, to sins of reason, and finally to sins of betrayal. The Seventh Circle, with its suicides and profligates, reveals perhaps the most tragic expressions of violence: when the soul turns upon itself, or burns through its own gifts in frenzied futility.

To Dante, sin is not mere behaviour, it is a deformation of the soul’s relationship to God, reason, and love. And Hell is not simply punishment, it is the soul perfected in its chosen disorder, suspended in a justice that mirrors its own decisions.

To read Inferno is to look not only at the damned, but at ourselves, not to predict our fate, but to refine our will.