Dante’s Inferno presents the Seventh Circle of Hell as the realm of suicides and profligates, those who destroy the self, whether through despair or excess. This article explores the theological, philosophical, and symbolic dimensions of their punishment, revealing a moral economy where the will, once corrupted, leads to irreversible ruin, the ultimate truth: suicide is irredeemable.

In the Inferno, the first canticle of The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri constructs a moral topography of the human soul, drawing its geometry not from the linear logic of modernity, evolving into Cartesian rationalism, but from Aristotelian ethics and Thomistic theology. Within this topography, the Seventh Circle of Hell is reserved for acts of violence, subdivided not by victim, but by object: against others, against God, and, pivotally, against the self. It is in the second ring of this circle that we encounter those who have committed suicide and, adjacent to them, the profligates, those who squandered their lives through reckless abandon.

To the modern reader, especially one conditioned by secular psychologies or liberal sympathies, the placement of suicides in Hell may seem an affront. But to understand Dante’s cosmology is to enter a framework in which human will, rightly ordered, is the highest faculty, and where suicide is not merely a tragic escape but an ontological rupture, violenza contro sé stessi, a rejection of the gift of life, which Aquinas and Augustine considered a fundamental violation of natural and divine law.

Contents

The Wood of the Suicides: Metaphysics in Arborial Form

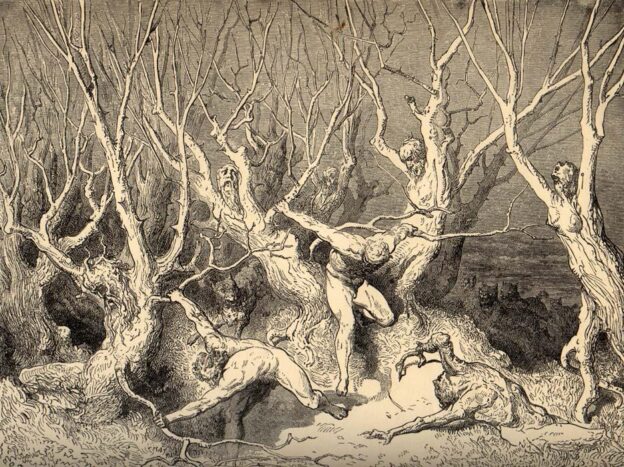

In Inferno Canto XIII, Dante and his guide Virgil enter a grotesque woodland, a “dusky wood” filled not with sinners wandering, but with trees. These are the souls of the suicides, their punishment a harrowing symbolic inversion: having rejected their human form in life, they are denied it in death. Twisted into trees, they can only speak when broken, when Dante snaps a branch from one, it screams with pain and bleeds dark ichor, an image both viscerally violent and symbolically apt.

Pier della Vigna, a trusted advisor to Emperor Frederick II, is the voice of this canto, emblematic of the noble suicide. Wrongly accused and imprisoned, Pier took his own life. He speaks not with bitterness, but with a kind of tragic stateliness, lamenting the corruption of the imperial court and his own fall from grace. His words are a study in dignity and defeat:

“I am the one who held both keys to Frederick’s heart, turning them, locking and unlocking with so soft a touch that I kept his secrets from all others. Faithful was I to that glorious office, so that because of it I lost my sleep and pulse.”

Dante does not withhold compassion from Pier, nor does he exonerate him. In the strict logic of the Commedia, suicide remains a sin not of despair alone, but of distorted pride, superbia, a belief that one can determine the value or end of one’s existence outside divine ordinance.

The transformation into trees is not merely punitive but diagnostic: in medieval thought, the soul and body were integrated substances. To sever the self through suicide was to reject one’s nature as a rational, ensouled being. In post-Dantean psychology, we might speak of alienation or mental illness; Dante instead gives us metaphor and metaphysics: the human soul, self-disfigured, becomes something less than human.

The Profligates: Hounds, Fury, and Waste

Not far from these rooted souls run the profligates, those who destroyed not themselves directly, but their lives, their fortunes, and by extension, their selves. They are pursued perpetually by black bitches, savage hounds who tear them apart, only for the souls to reconstitute and be chased anew. Here we meet Lano da Siena, a spendthrift noble, and Jacomo da Sant’Andrea, who set fire to his own property in manic extravagance.

Unlike suicides, who annihilate, the profligates dissipate. Their vice is not despair but excess, the Bacchic opposite of stoic virtue. Their punishment, in contrast to the rooted inertia of the suicides, is one of frenetic dismemberment. If the suicides suffer the consequences of negation, the profligates suffer those of ungoverned appetite, incontinentia taken to its destructive extreme.

It is here that Dante offers an early critique of the economic irrationality of wanton consumption. The term “profligacy” in classical and scholastic thought was more than financial mismanagement, it was a moral and social disorder, an offence against eudaimonia (flourishing), rooted in the failure to balance needs with means. This anticipates, obliquely but profoundly, the later critiques of capitalism by thinkers such as Thorstein Veblen or John Ruskin, for whom the spectacle of waste was not just inefficient but spiritually corrosive.

The eternal chase of the profligates mirrors the modern condition of consumerism in acceleration, desire feeding on itself, bound not by purpose but by its own momentum. In this way, Dante’s seventh circle can be read not only theologically but economically, as an allegory of unsustainable expenditure, of the self as a resource burnt through without wisdom or restraint.

A Circle That Refuses Consolation

What distinguishes the suicides and profligates from other sinners in Dante’s Inferno is the absence of active malice. These are not murderers or heretics or traitors; their violence is inward or diffuse, their sin rooted in despair, futility, or compulsion. And yet, precisely because their sin involves the will, its misuse, its abdication, they are judged with rigour.

Dante’s treatment of suicide has provoked much discomfort among modern interpreters, particularly in light of contemporary understandings of mental health. But to reduce Dante’s vision to cruelty is to miss the point. He is not writing a treatise on psychiatry but a poetic summa on the soul’s journey toward God. Within this framework, despair, infernally final, represents not sadness but the refusal of hope, which in Christian eschatology is the precondition of salvation.

Other Mentions of Suicide and Self-Destruction

In The Divine Comedy, suicides appear most prominently in Inferno, Canto XIII, where Dante places them in the Seventh Circle, Second Ring of Hell, the “Wood of the Suicides”. However, there are a few other significant moments where suicide appears, either implicitly or thematically, in Dante’s broader cosmology across the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Here are the key examples:

1. Inferno, Canto XIII – The Suicides Proper

As previously discussed, the suicides are in:

Seventh Circle (Violence) → Second Ring (Violence against Self)

Transformed into gnarled, thorny trees, their human forms lost because they renounced them. Pier della Vigna is the main speaker, joined by unnamed others (e.g., Lano da Siena and Jacomo da Sant’Andrea, who are profligates but connected thematically).

2. Inferno, Canto XIII & XIV – Suicides and Profligates

The profligates, who destroyed their lives through waste, aren’t suicides in the literal sense but are closely associated. Dante groups them spatially, suggesting a moral kinship between intentional self-destruction (suicide) and reckless squandering (profligacy).

3. Inferno, Canto XXVIII – Suicidal Imagery in the Schismatics

Though not suicides per se, the Schismatics in the Eighth Circle (Fraud), Ninth Bolgia suffer a symbolic dismemberment. The grotesque image of Bertran de Born carrying his severed head like a lantern metaphorically echoes the violence of suicide, as he describes his punishment as the separation of intellect from body.

This is a metaphysical echo of the self-murder that the suicides commit, a sundering of unity.

4. Purgatorio, Canto XIII – Allusions in the Terrace of Envy

On the Second Terrace of Purgatory (Envy), Dante hears a story referencing Sapia of Siena, who did not commit suicide but wished for her own ruin. Her sin was not against herself, but she confessed to a desire for self-destruction through the ruin of others, a psychological cousin of suicide.

5. Purgatorio, Canto XIV – Rebirth of the Body

In this canto, Dante discusses the resurrection of the body, and the implication for the suicides is stark: because they destroyed their bodies, they will not fully reclaim them on Judgment Day. Their shade will drag their bodies back into the woods, hanging them on the thorn trees that they became, a final and grotesque fusion of body and punishment.

6. Paradiso – Absence Speaks Volumes

In Paradiso, suicides are not present, which is entirely the point. Unlike other sins that may be purged (lust, pride, envy), suicide, as a rejection of divine providence and hope, is traditionally unredeemable in Dante’s moral framework. The absence of any mention or redemption of suicides in Heaven is telling.

7. Vita Nuova and Epistles – Dante’s Broader Views

Outside The Divine Comedy, Dante’s Vita Nuova and some of his letters hint at his views on despair, will, and mortal sin, reinforcing the theological context: suicide is the ultimate rejection of divine grace, the endpoint of acedia (spiritual sloth or despair), a theme running throughout his work.

Summary Table of References

| Work | Location/Reference | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Inferno XIII | Seventh Circle, Ring II | Main depiction of suicides (Pier della Vigna, forest of souls) |

| Inferno XIII–XIV | Border with profligates | Thematic link to self-destruction through waste |

| Inferno XXVIII | Eighth Circle – Schismatics | Symbolic echoes of self-dismemberment |

| Purgatorio XIII | Second Terrace – Envy | Psychological despair, desire for ruin |

| Purgatorio XIV | Resurrection doctrine | Suicides denied full resurrection of body |

| Paradiso (General) | No suicides appear | Reinforces finality of their choice in Dante’s theology |

Suicide Is Irredeemable

In Paradiso, suicides are not present, which is entirely the point. Unlike other sins that may be purged (lust, pride, envy), suicide, as a rejection of divine providence and hope, is traditionally unredeemable in Dante’s moral framework. The absence of any mention or redemption of suicides in Heaven is telling.

In Purgatorio, souls labour toward purification and eventual ascent. The terraces of the proud, the lustful, the envious, all are given a path to reformation through penance. But suicide is marked not merely as sin, but as a final act, a theological foreclosure. It precludes the arc of redemption that structures the Comedy itself. The will, by which all moral action is judged, here turns fatally inward. And with that, the narrative of salvation, so central to Dante’s poetic structure, ends not in upward motion, but in petrification.

Dante does not lack compassion for these souls. His writing is suffused with pathos. But he does not contradict the logic of his system to accommodate it. The infernal permanence of the suicides is not an oversight, but a consequence. Hell, in Dante’s cosmology, is not punishment imposed; it is the perfected form of one’s choices made absolute.

Concluding Reflections: Between Ethics and Empathy

To engage seriously with Dante’s Seventh Circle is to walk a narrow path between moral clarity and human sympathy. The suicides and profligates inhabit a space where theology and psychology overlap, where metaphysical error and emotional anguish blur. Dante’s genius lies in his ability to maintain both poles: to condemn the sin while honouring the tragic dignity of the sinner.

And perhaps this is the true gift of The Divine Comedy: not that it tells us whom to judge, but how to mourn, how to hold moral complexity without surrendering to moral relativism. In the forest of the suicides and the hunted plain of the profligates, we are not only shown what it means to fall, but what it means to forget how to stand.

It may be true that suicide is irredeemable, but forgiveness lies within us all.

RIP Peter James Horkan (1992) and David “Sid” Davies (2013)

Requiescant in pace. Miserere nobis, Domine.