This article explores how masking, often necessary for those with Asperger Syndrome, complicates the accuracy of personality typing systems. Drawing from personal experiences in a challenging post-war inner-city environment, it critiques the limitations of these systems in truly capturing one’s authentic self and offers insights into the interplay between identity, masking, and neurodiversity.

Introduction

As someone diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome, I have spent much of my life navigating the complexities of social interactions by “masking”, adopting behaviours that I believe others expect from me to fit into various social situations. Recently, I participated in the NCSC for Startups Accelerator Programme, where I encountered several modules on personality types. This exposure led me to write extensively on the subject, not out of belief in the systems, but from a combination of scepticism and a desire to understand what makes these theories so popular. You can discover the articles I wrote on Personality Types via this link https://horkan.com/category/personality-types

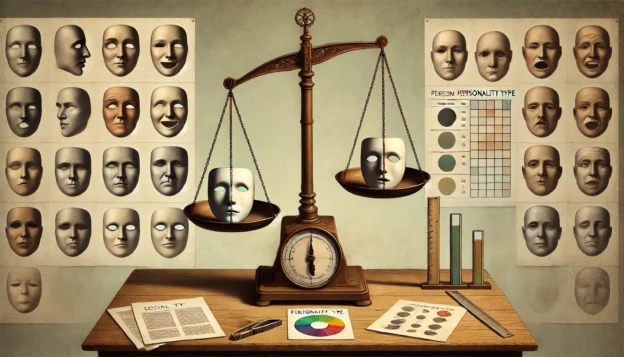

In this article, I aim to explore the intersection of masking and personality typing, particularly from the perspective of someone with Asperger Syndrome. How do these systems align with, or conflict with, the experience of masking? Can they truly capture the complexities of an individual’s personality, especially when that individual is often performing a role rather than expressing their authentic self?

This article was inspired by my time on the National Cyber Security Centre‘s NCSC for Startups accelerator programme on behalf of Cyber Tzar.

Understanding Masking

Masking is a concept familiar to many people on the autism spectrum. It involves consciously suppressing or altering one’s natural behaviours to conform to societal expectations. This can include mimicking facial expressions, adjusting tone of voice, or even adopting entirely different personas in different social contexts. For those with Asperger Syndrome, masking can become second nature, a survival mechanism in a world that often does not accommodate neurodiversity.

The reasons behind masking are multifaceted. It can stem from a desire to fit in, to avoid negative attention, or simply to get through social interactions with as little friction as possible. For me, this was particularly influenced by my upbringing in an inner-city environment during the post-war period and the “winter of discontent” era. In those circumstances, not fitting in was never a choice; survival often depended on conformity and blending in with one’s surroundings. However, the cost of masking is significant. It can be mentally and emotionally exhausting, and over time, it may lead to a sense of disconnection from one’s true self.

Overview of Personality Typing Systems

Personality typing systems, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Big Five, and the Enneagram, are designed to categorise individuals based on their traits, behaviours, and preferences. These systems are often used in professional and personal development to better understand oneself and others, with the assumption that personality types are relatively stable and can predict behaviour across various situations.

The appeal of these systems lies in their simplicity and the sense of order they bring to the complexity of human behaviour. They offer a framework for understanding differences between people and can provide insights into interpersonal dynamics. However, the validity and reliability of these systems are often debated, particularly when considering individuals whose behaviours might not align neatly with the categories these systems propose.

The Intersection of Masking and Personality Typing

For someone who frequently masks, personality typing systems can present a conundrum. The persona that emerges through masking may not reflect the individual’s true preferences or behaviours, yet it is this persona that might be captured by personality assessments. This raises a critical question: Can these systems accurately assess someone who is not fully expressing their authentic self? What even is the authentic self after half a century of masking?

Masking complicates the relationship between one’s true personality and the traits identified by these typing systems. For instance, an individual who masks may appear more extroverted or agreeable than they genuinely feel, skewing the results of a personality assessment. Consequently, the personality type assigned might reflect the “masked” version of the individual rather than their core self.

Moreover, the emphasis on fitting people into predefined categories can be particularly limiting for those on the autism spectrum. Personality is fluid and multifaceted, and the rigidity of typing systems may overlook the nuances of an individual’s experience, especially when that experience involves navigating the world through a carefully constructed façade.

Personal Reflection and Insights

In my journey of exploring personality types, I have often found myself questioning the validity of these systems, especially in the context of my own experiences with masking. Over the years, I have been assigned differing personality types at different times, despite the common assertion by Myers-Briggs assessors that personality type remains relatively stable, changing only marginally, if at all, throughout a person’s life. There is a certain irony in attempting to categorise oneself using a framework that seems ill-equipped to account for the complexity of a life spent adapting to external expectations.

Through my writings, I have come to see personality types not as definitive labels but as tools, imperfect, yet occasionally useful. They offer a starting point for self-reflection, but they should not be seen as the final word on who we are. For those of us who mask, it is crucial to recognise the limitations of these systems and to approach them with a healthy dose of scepticism.

In my own experience, the most valuable insights have come not from the labels themselves but from the process of questioning and exploring them. By engaging critically with these concepts, I have been able to better understand the ways in which I present myself to the world and the underlying motivations for my behaviours. This has, in turn, helped me to navigate social interactions with a greater sense of self-awareness.

Conclusion

Personality typing systems offer a simplified lens through which to view human behaviour, but they fall short in capturing the full complexity of those who frequently mask. For individuals with Asperger Syndrome, these systems may provide some insight, but they are ultimately limited by their inability to account for the nuances of a life spent adapting to external expectations.

As we continue to explore the intersection of personality, neurodiversity, and social dynamics, it is important to approach these systems with a critical eye. Rather than relying on them as definitive assessments of our character, we should use them as tools for self-exploration, always mindful of their limitations.

In the end, the most important journey is not in finding the right label, but in understanding and embracing our true selves, however complex or multifaceted that self may be.