Modern Koan from Dune of “Fear Is the Mind-Killer” is not a Zen story, nor is it a koan in the traditional sense. There’s no paradox or puzzle to unravel. But it carries the same contemplative weight. Spoken by Paul Atreides as part of the Bene Gesserit litany, it is a mantra about fear, presence, and the self that remains. Like a koan, it doesn’t resolve the moment; it holds us within it.

As with The Zen Koan of the Tigers and the Strawberry and The Zen Koan of the Two Monks, the Woman and the River, this reflection asks not how we control life, but how we respond to what we cannot.

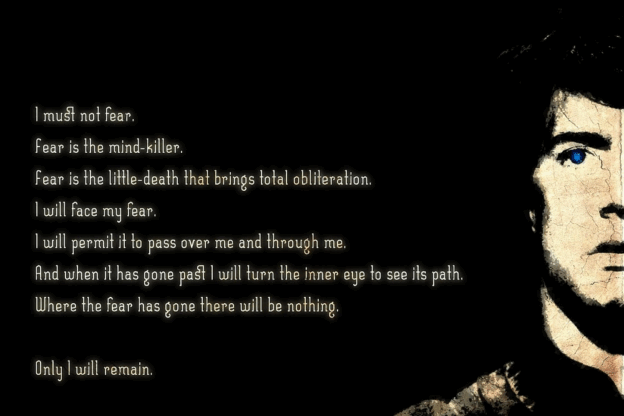

“I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it has gone past I will turn the inner eye to see its path.

Where the fear has gone there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.”

This passage reads like a meditation. It’s not about bravado or defiance, it’s about letting go. Paul Atreides doesn’t seek to destroy fear, only to see it clearly. He stands still and allows it to move through him. No resistance. No denial. No attachment.

Zen asks the same. To sit with discomfort. To notice fear without becoming it. The litany doesn’t promise survival or success, it promises clarity: that what is essential in us cannot be touched by fear if we allow it to pass.

And in that, we hear echoes of another voice, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar:

“A coward dies a thousand times before his death, but the valiant taste of death but once.”

Both the Bene Gesserit litany and Shakespeare’s line point to the same truth: fear can cause us to shrink back again and again, to suffer in advance, to abandon ourselves before anything has truly happened. But courage, real courage, is presence. It is the choice not to flinch from the moment. Not to collapse into the idea of what might come.

This koan doesn’t offer a plan or a promise. It offers a mirror. Fear will come. But we are not fear. We are what remains when it has passed. It’s a lesson in quiet resilience, in not abandoning ourselves in the face of imagined endings. In letting go of the little deaths before they accumulate. And in that, perhaps, is a deeper kind of freedom, not from death, but from the dying we do every day when we live in fear.

This modern koan doesn’t offer a neat resolution but invites stillness. Paul doesn’t fight fear, he lets it pass through, observing what remains. Like the ancient Zen masters, he trusts what endures once fear has moved on. Shakespeare’s line reminds us that it’s not death we suffer most, but the retreat we make from life in its shadow.

It’s a lesson in staying present, in facing what arises without flinching, and in letting go of the little deaths that fear brings. What remains is not certainty, but self, self-undiminished, intact, and quietly free.