This article, the culmination of my reflections on the myth of the West, deconstructs the utopian dream of the Western frontier, exploring its evolution from Manifest Destiny to Silicon Valley. Through historical analysis, literary critiques, and a look at Hollywood’s portrayal of the West, it examines how the promise of freedom and opportunity often fell short, revealing the complexities of the Western ideal. For me, this myth resonates deeply, intertwined with personal influences like Celtic romanticism, family legacies, and cross-cultural inspirations from Kurosawa.

Introduction: The West as Utopian Ideal

The myth of the West has long served as a powerful symbol of freedom, opportunity, and reinvention, woven into the fabric of American and global culture. This utopian vision, rooted in the early dreams of Manifest Destiny, bolstered by Hollywood, and mirrored in contemporary ideals like Silicon Valley’s promise of digital prosperity, captures a unique blend of hope, resilience, and rugged independence. Yet, these ideals also mask the harsh realities of Western expansion, where conquest, exploitation, and disillusionment lie beneath the surface of its promise.

In this article, the culmination of my reflections on the Western myth, we’ll explore its intricate layers, from the historical foundations of Manifest Destiny and frontier life to failed utopian communities, literary critiques, and Hollywood’s role in myth-making. Each section dissects a different aspect of the myth’s evolution:

- Historical Foundations: Explores Manifest Destiny and the myth of the frontier, showcasing how these ideas fueled westward expansion.

- Failed Utopias and Hostile Landscapes: Examines the failed intentional communities and environmental challenges faced by pioneers, and how the landscape itself challenged utopian visions.

- Gold, Greed, and Ghost Towns: Analyzes economic booms and busts, from the Gold Rush to the tech industry, and their lasting environmental and social impacts.

- Western Literature and Hollywood Mythology: Highlights the critiques from authors like Steinbeck and McCarthy, and Hollywood’s role in romanticizing, and later revising, the Western myth.

- Modern Critiques: Considers the lasting disillusionment with the American Dream and the impact of Silicon Valley, the new frontier of innovation, on the Western narrative.

This article aims to unravel the paradox of the Western dream, a beacon of hope and opportunity that remains elusive for many. For me, this myth is deeply personal, intertwining with my own love of Celtic mythology, my grandfather’s passion for Westerns, my admiration for Dashiell Hammett, and Akira Kurosawa and his cross-cultural legacy.

This article was inspired by conversations with my son, Bill, during his time at the University of Birmingham, on his degree course in English Literature. This article is the thirteenth and final article in my “Myth of the West” cycle.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The West as Utopian Ideal

- Historical Foundations: Manifest Destiny and the Frontier Myth

- Failed Utopias: Intentional Western Communities

- Gold, Greed, and Ghost Towns: Economic Utopias Gone Wrong

- Western Literature and the Shattered Ideal

- Dystopian Fiction and the West

- Ecological Utopia or Disaster?

- Mythology Betrayed

- Hollywood’s Myth of the Western Dream

- Broken Promises and Resentment

- Silicon Valley and the New Western Utopia

- The Digital Frontier: Innovation, Opportunity, and the American Dream

- Economic Inequality and the Broken Promises of the Tech Utopia

- Environmental Impact and the Illusion of Digital Sustainability

- Surveillance, Data Privacy, and the Loss of Personal Freedom

- The Disillusionment of the New Western Utopia

- Silicon Valley as the New Frontier, and the New Myth

- The “American Dream” and Western Disillusionment

- Origins of the American Dream and Its Western Roots

- Economic Inequality and the Fraying of the American Dream

- The American Dream as a Mirage for Marginalized Communities

- The Erosion of Social Mobility and Community Trust

- The American Dream as an International Ideal, and the Reality of Disappointment

- The American Dream and Western Disillusionment: A Paradoxical Legacy

- Freedom is a Lie

- Embracing the Myth: Why We Still Love the West and the American Dream

- Conclusion: The Paradox of the Western Dream

Historical Foundations: Manifest Destiny and the Frontier Myth

The myth of the West as a land of promise and opportunity can be traced back to the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, an ideology that framed westward expansion as both a right and a moral duty for Americans. Coined by journalist John L. O’Sullivan in 1845, the term encapsulated the belief that Americans were divinely destined to expand across the continent, carrying with them values of democracy, freedom, and civilization. “Our manifest destiny,” O’Sullivan wrote, “is to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” This statement established the West as a “promised land,” one that American settlers believed would offer freedom, prosperity, and a fresh start for those willing to claim it.

The Doctrine of Manifest Destiny and the Frontier Myth

The frontier myth added further allure to this vision, casting the West as a blank slate where individuals could rise above the constraints of Eastern society. Figures like Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett became folk heroes, embodying the ideal of rugged individualism and independence. The frontier was romanticized as a place where ordinary people could transform themselves through courage, hard work, and perseverance. In the words of historian Frederick Jackson Turner, who articulated the Frontier Thesis in 1893, “the frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization.” Turner argued that the constant movement westward shaped the American character, making it bold, democratic, and innovative. This perception of the West as a formative force in American identity solidified the belief in the West as a utopian space.

Conquest and Dispossession: The Hidden Costs of Expansion

However, the idealized vision of the West obscured the reality of conquest and dispossession that underpinned Manifest Destiny. While the Western myth portrayed the land as open and unclaimed, it was home to hundreds of Indigenous nations with complex societies, cultures, and spiritual traditions. The westward expansion devastated these populations through forced removals, violent conflicts, and diseases brought by settlers. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 authorized the U.S. government to forcibly relocate Native American tribes from their ancestral lands, leading to events like the Trail of Tears, during which thousands of Cherokee, Choctaw, and other tribespeople died while being marched to reservations in the West.

By 1900, the Indigenous population had plummeted to under 250,000 due to war, displacement, and disease, a direct consequence of Manifest Destiny. Historian Richard White argues that the Western expansion involved “as much taking as giving,” noting that the U.S. government granted land to settlers at the expense of the Indigenous populations who had lived there for centuries. This violent foundation casts a shadow over the notion of the West as a utopia, revealing a dark undercurrent in the Western dream.

Environmental Exploitation and the Enduring Legacy

The physical and environmental impact of Manifest Destiny was equally significant. Expansionists saw the land as an endless resource to be cultivated and exploited, leading to practices that disregarded natural ecosystems. As settlers moved westward, they cut down vast forests, diverted rivers, and introduced farming and mining practices that disrupted local wildlife. The American Bison, once estimated to number in the tens of millions, were hunted nearly to extinction by the late 19th century, with only a few hundred remaining. This depletion symbolized the disregard for the land and its resources in the relentless pursuit of expansion and profit.

The legacy of Manifest Destiny and the frontier myth persists in American culture today, often romanticized in literature, film, and political rhetoric. The Western ideal continues to evoke a vision of independence and opportunity, even as its historical foundations reveal a legacy of dispossession, environmental exploitation, and broken promises. By examining the roots of the Western myth, we uncover a more complex and contested history, one that challenges the idyllic vision of the West as a utopian paradise.

Failed Utopias: Intentional Western Communities

The allure of the Western utopia was not limited to settlers seeking land or fortune; it also inspired groups of idealists and reformers who sought to create new societies founded on cooperation, equality, and shared values. These intentional communities viewed the West as a place where they could build idealized societies, free from the economic inequalities, religious constraints, and industrial pressures of the Eastern United States. The West promised a clean slate, and many believed it could be molded into a model society that would showcase the potential for human cooperation.

Among the most notable of these communities was Brook Farm, established in 1841 in Massachusetts by a group of Transcendentalist thinkers, including writer Nathaniel Hawthorne and educator George Ripley. Although it was located on the East Coast, Brook Farm represented the early ideals that would influence many Western utopian projects. It aimed to merge intellectual and physical labor, promoting both personal fulfillment and societal harmony. Hawthorne later left disillusioned, and he reflected on his experience in his novel The Blithedale Romance, satirizing the naïveté of utopian communities and foreshadowing the failures of many similar ventures that would arise in the West.

As the concept of the Western utopia expanded, pioneers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries began establishing experimental communities on the Western frontier, seeking fertile ground for their ideals. New Harmony in Indiana (founded in 1825) and Oneida Community in New York (founded in 1848) were initial attempts, but Western settlements like Llano del Rio in California and Zion City in Illinois became the most ambitious. These communities attracted individuals inspired by the ideals of socialism, anarchism, and religious reform, convinced that the West could serve as a fertile landscape for radical societal transformation.

Case Study: Llano del Rio

Founded in 1914 by Job Harriman, a former Socialist Party candidate for mayor of Los Angeles, Llano del Rio was one of the largest and most ambitious socialist colonies in the American West. Located in the Mojave Desert, Llano del Rio aimed to create a self-sustaining, cooperative society where land and resources were shared equally among members. It offered an alternative to the capitalist economy and promoted gender equality, with women holding leadership roles and equal pay. By 1917, it had grown to nearly 1,000 residents, with cooperative industries, schools, and a centralized government.

Despite its initial success, Llano del Rio soon faced significant obstacles. The desert environment made agriculture challenging, and water scarcity became a constant issue. Tensions arose among members as ideological divisions surfaced, and financial mismanagement added to the colony’s difficulties. By 1918, the community had disbanded, leaving its buildings abandoned. Llano del Rio’s failure illustrated the harsh reality of the Western landscape, where idealism often clashed with physical and economic realities.

Other Intentional Communities and Their Challenges

Similar attempts at utopian communities faced obstacles unique to the Western frontier. Zion City, founded in 1901 in Illinois by the controversial evangelist John Alexander Dowie, aimed to create a theocratic society based on Dowie’s religious doctrines. Dowie envisioned Zion City as a community that adhered to his strict moral code, banning practices like alcohol consumption and gambling. However, internal conflicts, financial mismanagement, and Dowie’s authoritarian rule led to the community’s collapse, and Zion City eventually evolved into a conventional town, abandoning its utopian principles.

In Colorado, Greeley, a cooperative colony established by Horace Greeley and Nathan Meeker in 1869, sought to create a community founded on principles of mutual support and temperance. Although Greeley initially thrived, conflicts over land distribution, internal disagreements, and the harsh environmental conditions led to its eventual transformation into a typical Western town, its original ideals largely abandoned.

In these communities, members often found that their utopian visions conflicted with the demands of survival and the pressures of individuality. Sociologist Rosabeth Moss Kanter describes such failures as “utopia in practice,” observing that idealistic communities inevitably confront practical limitations. “Community requires common values and goals,” Kanter writes, “but also necessitates compromise and resilience, qualities that are rarely abundant in experiments with idealism.” These failed utopias reveal the underlying tension between aspiration and reality in the Western myth, where high ideals struggled to sustain themselves in the face of physical hardship and human nature.

The West’s Hostile Landscape and the Limits of Idealism

The failures of these intentional communities underscore a crucial theme in the myth of the Western utopia: the belief in human ability to overcome the physical and social environment. The founders of Llano del Rio, Zion City, Greeley, and other communities saw the West as a blank canvas for their visions, overlooking the challenges posed by the Western landscape. Many of these communities were established in arid or difficult-to-farm areas, requiring infrastructure and resources that were hard to obtain.

Even with determination and collective willpower, the founders found that the Western land did not readily yield to their ideals. Water scarcity, extreme weather, and isolation from established trade routes strained the communities, and ideological conflicts often heightened the challenges. Historian Robert V. Hine noted that the West was a place where “idealism was often tempered by the unforgiving landscape,” a realization that transformed utopian dreams into disillusioned pragmatism.

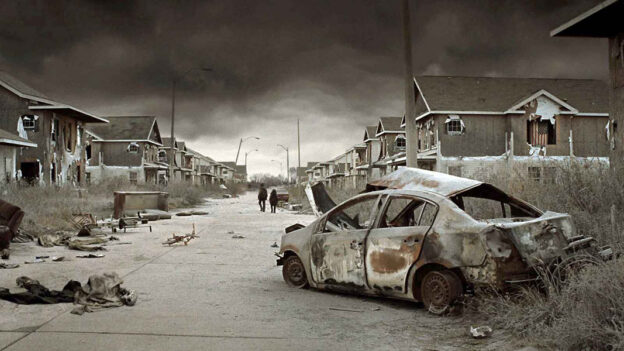

The story of these failed utopias reveals the broader paradox of the Western myth. While the West symbolized freedom, self-reliance, and community, it frequently shattered those very ideals. Rather than thriving, many of these communities struggled to sustain themselves, ultimately falling prey to the difficult realities of frontier life and the persistent struggle between individual needs and collective ideals. As these dreams crumbled, they left behind ghost towns, empty settlements, and monuments to ambition defeated by the forces of nature and human fallibility.

Gold, Greed, and Ghost Towns: Economic Utopias Gone Wrong

The dream of a Western utopia took on a new form during the mid-19th century as people from across America and the world flooded into California, Nevada, Colorado, and other parts of the West in search of gold, silver, and wealth beyond imagination. These gold and silver rushes offered the tantalizing promise of instant riches, spurring the rise of an economic utopia where, in theory, anyone willing to work hard could make a fortune and build a prosperous life.

The California Gold Rush of 1849 epitomized this phenomenon. By some estimates, over 300,000 people traveled westward within the first few years, hoping to stake a claim and strike it rich. San Francisco transformed practically overnight from a small town to a booming city, and other settlements quickly arose to accommodate the waves of miners and entrepreneurs who followed. California became synonymous with opportunity, embodying a utopian vision of individual prosperity and success. This pattern was repeated in places like Virginia City, Nevada (home to the Comstock Lode, the largest silver deposit in the United States), Leadville, Colorado, and other mining towns.

The potential for wealth created a fervent atmosphere, one filled with risk and fierce competition. The Gold Rush spirit permeated society, leading Mark Twain to observe that it was “not just an opportunity, but a fever, a mania that swept up anyone within its path.” In towns across the West, saloons, gambling dens, and hastily constructed houses sprang up, serving the needs of the diverse population that arrived, including Americans, Chinese immigrants, Europeans, and Latin Americans, each chasing the same utopian promise.

However, the reality of the gold rushes was far harsher than many had anticipated. The vast majority of miners returned empty-handed, spending months or even years laboring in dangerous conditions with little reward. For every successful claim, hundreds failed, and many left in poverty. By some estimates, only a small fraction, fewer than 5%, of miners actually made a significant profit from their endeavors. Moreover, mining was a perilous occupation: lung disease from dust inhalation, fatal accidents in tunnels, and clashes with other miners made survival a challenge in itself. This economic utopia, while promising riches, often led to disillusionment and hardship.

Environmental and Social Impacts of the Rush for Wealth

The environmental impacts of the Gold Rush and subsequent silver and mineral booms were devastating. Mining practices such as hydraulic mining and strip mining left scars across the landscape, damaging rivers, forests, and hillsides. Hydraulic mining, in particular, unleashed torrents of water to blast away mountainsides, filling rivers with sediment and destroying habitats. Historian J.S. Holliday described hydraulic mining as “an environmental disaster that forever altered California’s landscapes,” causing irreparable harm to ecosystems and local wildlife. In 1884, after years of unchecked mining damage, hydraulic mining was finally outlawed in California, a move that underscored the environmental price of the gold-driven utopia.

The social impacts were equally severe. The influx of miners and settlers led to violent confrontations with Indigenous tribes, whose lands were seized or destroyed by mining activities. The pursuit of gold and silver created tension between newcomers and the original inhabitants, often escalating to brutal conflicts that further displaced Native populations. In the words of historian Benjamin Madley, “the Gold Rush fueled a wave of violence and dispossession that fundamentally reshaped California.”

As resources dwindled, the populations that had boomed in mining towns dwindled just as quickly. These once-thriving settlements became ghost towns, empty, abandoned relics of failed promises. Ghost towns like Bodie, California, and Rhyolite, Nevada, now stand as stark reminders of the transient nature of the economic utopias of the West. In Bodie, for instance, the population soared to around 10,000 in the late 1870s but quickly declined after mines began to yield less ore. By 1915, Bodie was practically deserted. Today, it exists as a preserved ghost town, its empty streets and decaying buildings a silent testament to the dream that brought so many people westward, only to end in disappointment.

The Boom-and-Bust Cycle of Western Economics

The Gold Rush and similar mining booms established a boom-and-bust cycle that would define Western economies for decades. This pattern was later repeated with other industries, such as timber, oil, and railroads, each promising a new wave of opportunity and prosperity. But just like the gold rushes, these industries often brought temporary booms followed by swift declines, leaving behind economic instability, environmental degradation, and communities struggling to adapt.

The logging industry, which followed the expansion of railroads, decimated forests across the West in the name of progress. In states like Oregon and Washington, vast old-growth forests were cut down in a matter of years to supply timber for the rapid construction needed to support growing populations. As forests disappeared, so too did the economic stability of logging towns. By the mid-20th century, many of these towns faced economic collapse as resources ran out and environmental regulations curbed logging operations.

Similarly, the oil industry created temporary economic booms in areas like California and Texas but also left a legacy of environmental damage and economic disparity. Oil fields led to rapid job creation, but when the oil market declined or wells ran dry, towns that had flourished were left to grapple with rising unemployment and poverty. Environmental pollution from spills and drilling left lasting impacts on these areas, further revealing the destructive nature of the economic utopias that often drove Western expansion.

The Lasting Legacy of Failed Economic Utopias

The legacy of these boomtowns and ghost towns is still visible in the American West today. Ghost towns stand as physical reminders of the West’s utopian promises and their frequent failures. They tell a story of how the pursuit of profit, when untempered by sustainability or foresight, can lead to ruin rather than prosperity. In many ways, these abandoned towns serve as cautionary tales about the dangers of unchecked ambition and the fragility of economic utopias.

Today, scholars argue that the Gold Rush and similar booms contributed to a culture of short-term profit-seeking that still influences Western economies. Historian Richard White notes, “The boom-and-bust mentality created by the Gold Rush has left an enduring imprint on the American West. This region has often been governed by visions of sudden wealth rather than sustainable growth.” This approach has contributed to persistent economic challenges in the West, where industries such as real estate and tech continue to experience their own boom-and-bust cycles.

The story of gold, greed, and ghost towns underscores a recurring theme in the Western myth: that of the elusive utopia. For those drawn to the promise of wealth and opportunity, the West offered visions of instant success and prosperity. Yet, for the vast majority, it delivered only hardship, transience, and disappointment. The economic utopia that inspired so many to venture westward proved itself to be unsustainable, driven more by speculative ambition than by any lasting ideal. The dream of the West, like the riches it promised, often turned out to be fool’s gold.

Western Literature and the Shattered Ideal

For many, literature has been the lens through which the American West’s utopian ideals, and their eventual disillusionment, are most vividly explored. From the Dust Bowl novels of John Steinbeck to the dark, existential landscapes of Cormac McCarthy, Western literature has repeatedly examined the rift between the promise of the West and its harsh realities. These authors and their works have been instrumental in deconstructing the Western utopia, offering readers a complex vision of the West as both a land of opportunity and one of relentless struggle, exploitation, and moral ambiguity.

John Steinbeck and the Broken Promises of the West

Few authors capture the theme of shattered Western dreams as poignantly as John Steinbeck. In The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Steinbeck tells the story of the Joad family, “Okies” displaced by the Dust Bowl, who journey westward to California in search of a better life. The novel captures the intense hopefulness that many migrants felt as they sought a fresh start in the West, which, to them, symbolized abundance, freedom, and dignity. However, upon arriving in California, the Joads find that the promises of the West are largely hollow. Instead of opportunity, they encounter brutal working conditions, poverty, and exploitation. Farmers use deceptive wages to keep workers in poverty, while landowners hoard resources, turning the “promised land” into a site of despair.

Steinbeck’s work critiques not only the broken promises of the West but also the societal structures that perpetuate inequality and suffering. He describes the plight of the workers with visceral empathy, capturing their hopelessness and frustration: “How can you frighten a man whose hunger is not only in his own cramped stomach but in the wretched bellies of his children?” This statement highlights the disillusionment felt by those who believed in the West’s promise of economic freedom and found instead an unyielding reality of systemic exploitation. Through The Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck casts the West as a place that fails to live up to its utopian ideal, exposing the darker side of the American Dream.

Cormac McCarthy: The West as a Landscape of Moral Decay

While Steinbeck portrays the West as a site of exploitation and hardship, Cormac McCarthy goes a step further by depicting it as a landscape of existential dread and moral decay. In novels like Blood Meridian (1985) and The Road (2006), McCarthy transforms the Western landscape into a place where violence, lawlessness, and desolation are pervasive forces. His vision of the West is apocalyptic, almost biblical in its starkness, presenting a harsh critique of humanity’s relationship with the land and each other.

Blood Meridian, which is set in the mid-19th century, follows a young boy known as “the Kid” as he joins a group of Indian-hunters on a brutal journey through the American Southwest. The novel, inspired by historical events, portrays the violence that permeated Western expansion and questions the romanticized notion of the cowboy as a hero. McCarthy’s descriptions of the landscape are hauntingly desolate: “They crossed before dawn the low ground where the antelope had stood and the sand was pocked with their hooves like the tracks of rain in some old sea that was forever dry.” In McCarthy’s West, the land itself reflects an indifferent, even hostile, environment, underscoring the futility of human ambition against a landscape of such unforgiving scale.

Blood Meridian is notable for its portrayal of Judge Holden, a character who embodies the moral ambiguity and brutality of the Western myth. The Judge, an enigmatic figure who philosophizes on violence and power, symbolizes a darker vision of humanity. He operates without regard for moral laws, seeing violence as the true law of nature. “War is God,” the Judge declares, revealing McCarthy’s commentary on the West’s inherent brutality and the futility of idealistic visions of peace or redemption. Through the Judge and the merciless violence of the novel, McCarthy strips away the myth of the noble frontiersman, presenting instead a nihilistic view where survival and power outweigh any sense of moral duty.

This theme carries into The Road (2006), where McCarthy sets his story in a post-apocalyptic wasteland that bears a striking resemblance to the desolation of the American West. The novel follows a father and son as they navigate a barren, dangerous landscape, struggling to survive in a world stripped of civilization and hope. In The Road, McCarthy reduces the West to its most elemental, a space where humanity’s worst tendencies are laid bare in the absence of societal constraints. The father’s enduring love for his son stands as one of the few remnants of moral integrity, yet even this bond is overshadowed by the cruelty and desperation of those around them.

Through Blood Meridian and The Road, McCarthy subverts the traditional Western myth, portraying the West not as a land of freedom and opportunity but as a realm of moral decay and existential despair. His work underscores the notion that the Western ideal, when stripped of its romantic veneer, reveals an unvarnished reality where survival often requires the sacrifice of one’s humanity.

Joan Didion: Disillusionment in the California Dream

Another significant voice in critiquing the myth of the West is Joan Didion, whose essays explore the disillusionment that permeates California, the ultimate destination of the Western migration. In her seminal essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Didion delves into the cultural and moral fragmentation she perceives in California during the 1960s. For Didion, the West, and particularly California, embodies a failed promise, a land that has been endlessly marketed as a paradise but consistently fails to live up to this ideal.

Didion’s essay “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream” presents a scathing view of the California dream as a mirage, symbolizing a moral emptiness that exists beneath the surface of wealth and opportunity. She describes San Bernardino Valley as a place where “all that is promised by the myth of California, the blessings and the myths that have shaped our West, is brought to dust.” In Didion’s portrayal, California, synonymous with the American Dream itself, becomes a site of moral and cultural decay, a place where ambition and self-interest have eroded any sense of community or shared purpose.

In her essay “Goodbye to All That,” Didion recounts her personal disillusionment with the promises of the West Coast lifestyle. Having grown up in California, she was steeped in its myths of sunshine, freedom, and possibility. Yet as she matured, she found that these ideals were fleeting, often masking a reality of isolation and disconnection. Her work offers a profound critique of the Western dream as something ultimately ephemeral, a vision that crumbles under the weight of its own contradictions.

Thomas Pynchon: The West as Exploitation and Conspiracy

In Against the Day, Thomas Pynchon explores the American West at the dawn of the 20th century as a place dominated by exploitation, corporate interests, and conspiracy. Far from a land of individual freedom, Pynchon’s West is fraught with control and manipulation, where powerful industries and shadowy networks vie for influence.

Set against historical events like the Colorado Labor Wars and the Ludlow Massacre, Pynchon’s portrayal of mining communities in Colorado reveals the brutal realities beneath the promise of Western prosperity. His characters, including anarchists, laborers, and scientists, become entangled in violent power struggles fueled by corporations that control resources and exploit labor. The West, rather than a utopia of opportunity, becomes a battleground where idealism is overwhelmed by corporate greed and systemic injustice.

Pynchon’s depiction emphasizes the West as a place of paranoia and disillusionment, a stark contrast to its romanticized image. In this vision, technological progress and economic expansion serve as tools for domination rather than liberation, challenging the myth of the West as a land of freedom and possibility. Through this critique, Pynchon joins authors like McCarthy and Didion in exposing the contradictions of the Western dream, revealing how ambition and greed have distorted the utopian ideal.

The Grapes of Wrath, Blood Meridian, and Beyond: The Western Landscape as Metaphor

In The Grapes of Wrath, Blood Meridian, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and countless other works, the Western landscape itself emerges as a powerful metaphor for the failures of the utopian ideal. For these authors, the land reflects the illusions and aspirations that define the myth of the West, as well as the relentless forces that shatter these dreams. In Steinbeck’s California, the lush fields and orchards that symbolize abundance turn out to be a place of exploitation and struggle. In McCarthy’s West, the vast deserts and barren plains serve as a brutal reminder of humanity’s impermanence and insignificance. And for Didion, California’s sunny beaches and glamorous cities mask a sense of profound disillusionment and fragmentation.

Literature of the American West offers readers a counter-narrative to the traditional myth, revealing the West as a place where dreams often come to die. It presents the West not as an untouched paradise or a land of perpetual opportunity, but as a space where human ambition and moral complexity collide with a landscape that remains indifferent to human ideals. Through these stories, Western literature critiques the utopian promises of the West, illustrating that the reality of the Western dream is often one of hardship, sacrifice, and shattered illusions.

Dystopian Fiction and the West

Dystopian fiction has long served as a medium for exploring humanity’s darkest futures, and the American West provides a fitting backdrop for these grim visions. In the dystopian landscape, the myth of the West, once celebrated as a place of freedom, new beginnings, and abundant resources, is subverted, revealing a world plagued by environmental collapse, social decay, and moral ambiguity. Authors such as Cormac McCarthy and J.G. Ballard use the West to dismantle the myth of the frontier as a land of endless opportunity, portraying it instead as a place of desolation and survival.

Cormac McCarthy: The Western Apocalypse in The Road

In The Road (2006), Cormac McCarthy crafts a post-apocalyptic vision of America that reduces the Western myth to its most essential, and bleakest, elements. Set in a world devastated by an unspecified cataclysm, The Road follows a father and his young son as they navigate a barren, ash-covered landscape. The once-fertile West is transformed into a desolate wasteland, stripped of life and resources, where the dream of prosperity has been replaced by a brutal fight for survival.

The father and son’s journey through the ruins of Western civilization symbolizes the collapse of not only the environment but also of the moral and social structures that once defined society. They encounter bands of cannibals, deserted cities, and remnants of a society that has lost all hope. McCarthy’s sparse prose mirrors the barrenness of the world he depicts, where even language seems to erode alongside humanity’s decayed values. The father’s only source of motivation is to “carry the fire” for his son, a faint glimmer of morality in a world where survival often demands ethical compromise. McCarthy’s West is thus a dystopian inversion of the frontier ideal, a place not of freedom, but of moral decay and existential despair.

J.G. Ballard: Environmental Collapse in Hello America

J.G. Ballard, in Hello America (1981), offers another dystopian take on the Western myth, imagining a future where America has been abandoned due to environmental collapse. Set in a desolate, post-apocalyptic United States, the novel follows a group of British explorers who venture across the Atlantic to rediscover a country that has long been left to ruin. Ballard’s West is a desert wasteland, a place where natural disasters and human neglect have erased the vibrant landscapes that once defined it.

As the explorers journey across the empty plains and ghost towns, they encounter echoes of a former empire that fell victim to its own excesses. Ballard’s dystopian West serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the environmental consequences of unchecked consumption and industrialization. The novel critiques the very notion of the West as a land of limitless opportunity, portraying it instead as a symbol of humanity’s failure to live sustainably. Through Ballard’s bleak vision, the West becomes a warning against the dangers of ecological hubris and the folly of believing that resources, and opportunities, are inexhaustible.

Philip K. Dick and the Erosion of Reality in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

In Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), the West is portrayed not through its physical landscapes, but through the erosion of reality and identity in a world dominated by technology and commodification. Set in a post-apocalyptic future where much of the planet is irradiated, the novel follows bounty hunter Rick Deckard as he hunts rogue androids in a decayed San Francisco. The Western ideal of individualism and freedom is here transformed into a bleak vision of isolation and alienation, where even human identity has become ambiguous.

Dick’s dystopian West subverts the myth of rugged individualism, showing instead a society in which technology and consumerism have alienated individuals from themselves and each other. The scarcity of real animals and the prevalence of artificial replacements reflect the degradation of nature and authenticity, central elements in the classic Western myth. The novel challenges the Western ideal of self-discovery, portraying instead a society where individuals struggle to even define what it means to be human. In Dick’s world, the frontier is no longer a place of self-reinvention but a bleak landscape of existential questions and lost connections.

The West as a Dystopian Symbol: Environmental Ruin, Moral Collapse, and the Failure of Progress

Together, these dystopian works by McCarthy, Ballard, and Dick depict the West not as a land of hope and new beginnings, but as a symbol of humanity’s darkest tendencies and failed aspirations. The dystopian West is stripped of its mythic qualities, revealing the consequences of environmental neglect, moral decay, and the relentless pursuit of progress without regard for sustainability. This vision of the West reflects modern anxieties about climate change, resource scarcity, and social fragmentation, transforming the Western myth into a cautionary tale for contemporary society.

The West, in dystopian fiction, becomes a canvas for exploring what happens when the dreams of freedom and prosperity give way to the realities of survival and decay. It serves as a stark reminder that unchecked ambition, greed, and exploitation can turn even the most promising landscapes into barren wastelands. In these stories, the myth of the West as a utopia is inverted, revealing the dangers that lie beneath the surface of humanity’s quest for progress and control.

Ecological Utopia or Disaster?

For many settlers and pioneers, the American West represented an ecological utopia, a place where new agricultural and irrigation methods could transform deserts and plains into thriving landscapes. The abundance of land offered the promise of self-sufficiency and productivity, and the unique ecology of the region inspired utopian visions of sustainable communities, lush farms, and vibrant cities. However, these dreams often clashed with the West’s harsh natural environment, leading to ecological disasters that transformed the landscape and undermined the utopian ideal.

The Irrigation Dream and the Transformation of the West

The promise of transforming arid Western landscapes into fertile farmland drove some of the most ambitious irrigation projects in U.S. history. Starting in the late 19th century, the federal government supported extensive irrigation projects aimed at “reclaiming” desert land for agriculture. The 1902 Reclamation Act was a landmark initiative that funded the construction of dams, canals, and reservoirs across the West, including iconic projects like the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington. These projects turned previously arid regions into productive farmland, allowing for the development of cities and agricultural communities in places like California’s Central Valley, Arizona, and Nevada.

For a time, it appeared that these projects were fulfilling the dream of an ecological utopia. The dams provided water and electricity to millions of people, enabling the growth of cities and the expansion of agriculture. California’s Central Valley, for example, became one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world, producing vast quantities of fruits, vegetables, and nuts. However, the success of these projects masked significant environmental costs. By diverting rivers, flooding valleys, and disrupting ecosystems, irrigation projects altered the natural landscape in ways that would have long-lasting, and sometimes disastrous, effects.

The Dust Bowl: A Man-Made Ecological Catastrophe

One of the most profound ecological disasters in the American West was the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, a result of both natural drought and unsustainable agricultural practices. As settlers moved westward, they transformed native prairie grasses into cropland, disrupting the soil’s natural structure. During the 1920s and 1930s, farmers expanded their operations to meet the demand for wheat, plowing millions of acres across the Great Plains. When drought struck in the early 1930s, the unprotected topsoil turned to dust and was swept away by strong winds, creating massive dust storms that devastated the region.

The Dust Bowl highlighted the environmental vulnerability of the West and the dangers of pushing the land beyond its natural limits. In the worst years of the Dust Bowl, an estimated 2.5 million people were displaced from their homes, forced to abandon their farms and migrate to other parts of the country. Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath famously portrays the plight of these “Dust Bowl refugees,” capturing the desperation of families who had believed in the West’s promise of abundance only to find themselves impoverished and uprooted. The Dust Bowl serves as a stark reminder that the utopian dream of the West often overlooked the region’s ecological realities, leading to profound human and environmental suffering.

The Colorado River: Overuse and the Myth of Endless Resources

The Colorado River is perhaps the most striking example of the environmental limits faced in the American West. The river was once seen as an inexhaustible resource capable of supporting agriculture, cities, and industry. Major Western cities like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Denver have relied on the Colorado River for water, as have millions of acres of farmland in California and Arizona. The construction of the Hoover Dam and the Glen Canyon Dam were celebrated as feats of engineering that would provide water and electricity to fuel Western expansion.

However, overuse of the Colorado River has led to severe ecological and economic consequences. Today, the river no longer reaches the Gulf of California, its natural endpoint, and water levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, two of the largest reservoirs in the U.S., are at historic lows. Climate change, population growth, and prolonged drought have exacerbated water scarcity, and experts predict that the region could face severe water shortages in the coming decades. The shrinking of the Colorado River is a testament to the myth of the West as an endless resource, revealing that even the most ambitious infrastructure projects cannot overcome the ecological limits of the land.

Environmental Degradation and the Loss of the Western Ideal

The environmental consequences of Western expansion have extended beyond water scarcity and soil erosion. The mining and logging industries, both integral to Western development, left significant scars on the landscape. Mining practices such as strip mining, hydraulic mining, and open-pit mining devastated forests, mountains, and rivers. By 1900, mining operations in states like California, Nevada, and Colorado had transformed landscapes, polluting rivers with toxic runoff and leaving barren, scarred lands in their wake. Logging, which fueled the construction boom of the early 20th century, led to the destruction of old-growth forests across the Pacific Northwest and the Sierra Nevada, drastically reducing biodiversity and altering local ecosystems.

Today, the environmental impact of Western expansion is evident in everything from depleted groundwater reserves in the Central Valley to pollution in abandoned mining towns. The Western dream of transforming the land into an ecological paradise has often resulted in unsustainable practices that leave behind degraded ecosystems and depleted resources.

The Lasting Legacy: A Cautionary Tale

The environmental history of the American West reveals a recurring theme: the desire to transform the land and bend it to human will, regardless of the cost. This impulse reflects the utopian vision of the West as a place where humanity can remake nature in its own image, yet the reality has often been one of ecological catastrophe. Historian Donald Worster describes the West’s environmental legacy as “a monument to human pride and human error,” arguing that the ecological limits of the West are a cautionary lesson for future generations.

In recent years, conservation efforts and sustainable practices have attempted to address some of the West’s environmental challenges. However, the legacy of environmental degradation serves as a reminder of the dangers of viewing the land solely as a resource to be exploited. The dream of an ecological utopia in the West, like many other aspects of the Western myth, remains an ideal that has repeatedly clashed with the realities of human impact and natural limits.

The story of the American West as an ecological utopia turned disaster reflects the broader paradox of the Western myth: that in seeking to create a paradise, humans often destroy the very resources and landscapes that make such a paradise possible. The West, once a symbol of freedom and possibility, now stands as a powerful reminder of the consequences of ecological hubris and the importance of sustainable stewardship.

Mythology Betrayed

The mythology of the West, the romanticized vision of a land of freedom, opportunity, and renewal, has roots stretching back to both European settlers and Indigenous beliefs. For pioneers, the West represented a promised land, a place where they could start anew and live in harmony with the land. Indigenous cultures, too, had long ascribed sacred meanings to Western landscapes, viewing them as realms of ancestral spirits, transformation, and balance. Yet, as settlers pushed westward and transformed the landscape, these myths, both Indigenous and settler, were shattered. The reality of the West exposed the utopian dreams of both groups as unsustainable, and in many cases, mere fictions.

Settlers’ Dreams and the “Land of Milk and Honey”

For European settlers, the West was initially promoted as a “land of milk and honey,” a biblical phrase that appeared frequently in promotional materials encouraging settlement. Pamphlets, newspapers, and railroads advertised the West as a region of untapped abundance, a place where fertile land and bountiful resources awaited those with the courage to venture into the unknown. This utopian promise was deeply rooted in European ideals of progress and the Enlightenment belief in human mastery over nature.

However, as settlers encountered the harsh landscapes of the Plains, deserts, and mountains, they found that the West did not conform to these idealized descriptions. Arid land, extreme weather, and scarce water resources made agriculture challenging, while remote locations hindered access to markets and supplies. Many settlers struggled to survive, let alone prosper. Historian Patricia Limerick argues that the myth of the West was an “imposed optimism” that covered the region’s reality of struggle and hardship, particularly as more and more settlers faced disillusionment.

The Homestead Act of 1862, which offered land to settlers willing to cultivate it, resulted in the displacement of Indigenous peoples and often failed to deliver on its promise. While nearly 1.6 million homestead applications were filed, only a fraction of those who attempted to “prove up” their land claims were able to make them sustainable. The land grants often went to those who were unprepared for the environmental challenges of the West, and by the late 19th century, many abandoned their claims, unable to reconcile the myth with the reality.

Indigenous Beliefs and the Broken Harmony with the Land

For Indigenous cultures, the West held a profound spiritual significance long before European settlers arrived. Many tribes considered Western landscapes to be sacred spaces imbued with the presence of ancestors and spirits. The Lakota people, for instance, viewed the Black Hills as a sacred site, while the Hopi and Zuni regarded the Southwest as the land where their people emerged. For Indigenous cultures, the land was not a blank slate or a place to be conquered; it was a living entity to be respected, an intricate part of a balanced ecosystem that sustained human life.

As settlers encroached upon these lands, forcibly removing Indigenous people and disrupting traditional ways of life, the Indigenous view of the West as a realm of harmony was shattered. With treaties repeatedly broken and sacred lands desecrated, Indigenous communities experienced a profound sense of betrayal. In the words of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, “The earth and myself are of one mind. The measure of the land and the measure of our bodies are the same.” The forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands was more than a displacement; it was a profound disruption of spiritual and cultural beliefs about the West. The myth of the harmonious landscape, carefully maintained through traditions of stewardship, was betrayed by the imposition of settler ideologies and practices.

The Western Dream as Illusion and Propaganda

The mythology of the West was, in many ways, a carefully constructed illusion, crafted by those who sought to profit from westward expansion. Railroads, land speculators, and government agencies all played a role in promoting the West as a utopian destination, selling an ideal that was far from reality. In the late 19th century, railroads circulated pamphlets and posters showing idyllic farms, lush orchards, and thriving communities. These images painted the West as a place where hard work would yield prosperity, tapping into the American ideals of individualism and self-reliance.

However, this portrayal was largely a form of propaganda. Railroads needed settlers to buy land, use their trains, and stimulate the economies of newly established towns along their routes. The government, too, sought to populate the West as a means of securing its claim over the continent and to capitalize on its resources. Historian Richard White points out that “the West was built on promises that could never be kept,” as much of the land was simply unsuitable for farming and required irrigation projects and extensive infrastructure to sustain communities.

The impact of these broken promises was significant. Settlers who had been lured westward by the vision of a new Eden were often disillusioned by the difficulties they faced, and many abandoned their homesteads to return east or to the growing urban centers. Those who stayed frequently found themselves trapped in cycles of debt and hardship, bound by the realities of an unforgiving landscape that defied their expectations.

The Betrayal of Environmental Ideals

Beyond the social and cultural disillusionment, the West’s environmental reality also betrayed the mythology that had been woven around it. The vision of the West as a lush, fertile paradise led to aggressive attempts to reshape the landscape, from damming rivers to clear-cutting forests and overgrazing prairies. This intensive development altered ecosystems and led to environmental degradation that was far from the ideal of a harmonious relationship with the land.

The Dust Bowl, discussed earlier, is a prime example of how settler ambitions to create an agricultural utopia ignored the ecological limits of the region. The devastation wrought on the land, coupled with a lack of sustainable practices, shattered the belief in an endlessly bountiful West. By the 20th century, the environmental costs of this mythology became starkly apparent, leaving communities to contend with the consequences of a land that could not meet the demands placed upon it.

Legacy of Betrayal and Disillusionment

The betrayal of the Western myth left a legacy of disillusionment that endures to this day. For many, the West represents a failed promise, a reminder of dreams deferred and ideals that were never achievable. The myth of the West as a utopia, a place of balance, abundance, and freedom, has been replaced by a complex understanding of the region as a place marked by struggle, hardship, and exploitation. The “land of milk and honey” was, for many, little more than a mirage, and both settlers and Indigenous communities were forced to confront the painful reality that the ideals they held were ultimately unsustainable.

In retrospect, the mythology of the West was perhaps always destined to be broken. Built on dreams that ignored the realities of the land and its people, the Western utopia was an illusion that could not withstand the pressures of settlement, industry, and environmental limits. Today, the myth of the West remains a powerful symbol in American culture, but its contradictions and failures serve as a cautionary tale, a reminder that utopian visions, when imposed on a land and its people without understanding, are destined to disappoint.

Hollywood’s Myth of the Western Dream

Hollywood has been one of the most influential forces in creating and sustaining the myth of the West, portraying it as a land of rugged individualism, heroic struggle, and moral simplicity. Western films and television shows have solidified the image of the cowboy as a symbol of American independence, courage, and perseverance. Through iconic films like Stagecoach (1939), Shane (1953), and The Searchers (1956), Hollywood created an enduring vision of the West as a place where good triumphs over evil, where the land is open for the taking, and where freedom reigns supreme. However, this image has often masked the darker aspects of Western expansion, including dispossession, violence, and environmental destruction, which would later become themes in revisionist Westerns as the genre evolved.

The Rise of the Classic Western: Cowboys, Outlaws, and the Frontier Hero

Hollywood’s classic Westerns of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s were instrumental in popularizing the myth of the Western hero. Films like Stagecoach and High Noon (1952) established the cowboy as a moral figure who embodies the values of justice, resilience, and courage. Played by actors like John Wayne and Gary Cooper, the cowboy hero became a national archetype, a rugged individual who operates outside the constraints of law and civilization but adheres to his own moral code. These films frequently emphasized themes of personal honor, loyalty, and the triumph of the lone hero over lawlessness and chaos, reinforcing the idea of the West as a place where character and conviction determined one’s destiny.

The landscape of the West in these films often served as a backdrop that mirrored the hero’s inner strength and freedom. Sweeping vistas, open plains, and majestic mountains became visual metaphors for the vast potential of the West, symbolizing both physical and spiritual freedom. The classic Western presented the frontier as an untamed space where individuals could reinvent themselves, free from societal constraints and open to new possibilities. This vision captured the imagination of audiences worldwide, transforming the West into a romanticized ideal.

The Darker Side of the Western Dream: Revisionist Westerns and the Challenge to the Myth

As the social and political landscape in America shifted during the 1960s and 1970s, so did the portrayal of the West in Hollywood. A new wave of revisionist Westerns emerged, challenging the simplistic morality and idealized heroism of earlier films. Directors like Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and Arthur Penn used the Western genre to critique American values, exploring themes of violence, moral ambiguity, and social decay. Films like The Wild Bunch (1969), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), and Little Big Man (1970) presented the West as a place of brutality and ethical compromise, undermining the myth of the cowboy as a virtuous hero.

In these revisionist Westerns, the cowboy is no longer a moral figure standing up for justice but often a conflicted character struggling with personal flaws and societal pressures. In Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), for example, the heroes are bounty hunters motivated by greed, forced to navigate a violent and corrupt world. Similarly, in The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah portrays a gang of aging outlaws facing the end of their way of life in a society that has moved beyond their code of honor. These films depict a West filled with violence and betrayal, where the line between good and evil is blurred, revealing the contradictions inherent in the Western dream.

Indigenous Portrayals and the Problem of Erasure

Classic Westerns often marginalized or stereotyped Indigenous characters, portraying them as obstacles to the progress of settlers or as faceless threats to be subdued. Indigenous people were rarely given complex roles or voices in these narratives, reinforcing a one-sided view of Western expansion as a heroic conquest. Revisionist Westerns, however, began to address these portrayals, offering more nuanced perspectives on Indigenous experiences.

Films like Little Big Man (1970) and Dances with Wolves (1990) attempted to portray Indigenous characters with greater complexity, highlighting the injustices they faced and challenging the romanticized image of the frontier. Little Big Man, directed by Arthur Penn, follows the story of a white boy raised by the Cheyenne, offering audiences a view of Western expansion from an Indigenous perspective. Similarly, Dances with Wolves, directed by Kevin Costner, centers on a U.S. Army officer who befriends a Sioux tribe, exploring themes of cultural understanding and respect. These films marked a significant shift in Hollywood’s portrayal of the West, acknowledging the historical erasure of Indigenous voices and offering a critique of the myth of Western heroism.

Hollywood’s Legacy: The West as a Symbol of America’s Ideals and Failures

Hollywood’s portrayal of the West has left a lasting impact on American culture and the world’s perception of the American Dream. The Western hero, independent, morally resolute, and willing to confront challenges head-on, became a symbol of American ideals. However, as Hollywood began to interrogate the darker aspects of the Western myth, the West also came to represent the nation’s failures: the violence, dispossession, and environmental degradation that underpinned its expansion.

Today, Hollywood continues to revisit the Western genre, often blending traditional themes with modern critiques. Films like No Country for Old Men (2007) and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) explore the West as a place of existential crisis and moral decay, using the familiar setting to reflect on issues like greed, justice, and the erosion of community values. These films offer a more complex view of the Western landscape, acknowledging both the allure and the disillusionment embedded in the myth of the frontier.

Hollywood’s evolving portrayal of the West reveals the persistent appeal of the Western dream, as well as its contradictions. Through both classic and revisionist Westerns, Hollywood has shaped the myth of the West into a powerful symbol of American identity, one that speaks to the nation’s aspirations and its unfulfilled promises. The West, as depicted in film, remains a place of both possibility and betrayal, a landscape where heroes confront not only external challenges but also their own limitations and the complexities of human nature.

Broken Promises and Resentment

The myth of the West, and more broadly, the American Dream, has been one of the United States’ most powerful exports, projecting ideals of freedom, prosperity, and self-determination. While this mythology inspired millions within the U.S., it also spread worldwide, often creating admiration for American values and ambitions. Yet, the American Dream, when idealized and promoted internationally, frequently clashed with complex global realities. The myth’s failure to deliver on its promises, coupled with the unintended consequences of American foreign policy, has led to significant resentment, especially in regions like the Middle East, where the ideals of the West are often perceived as both invasive and destabilizing.

The American Dream as a Global Ideal

The American Dream, closely tied to the Western myth of independence and opportunity, became a global ideal in the 20th century, particularly after World War II. The United States emerged from the war as a superpower and began to wield significant influence over global politics, economics, and culture. As American media and corporations expanded internationally, the ideal of the West as a land of freedom and prosperity was woven into films, literature, advertisements, and even political rhetoric. Images of the suburban home, the self-made individual, and the notion of upward mobility were disseminated worldwide, creating a powerful allure for the American way of life.

For many, this dream was deeply appealing. The American Dream offered a vision of individual potential, one that was not restricted by class or lineage, and a society where merit could pave the way to success. However, this vision also created expectations that were challenging to meet, even for those within the U.S. The myth of the West promised endless opportunities, yet as it spread globally, it often failed to acknowledge the systemic barriers and inequalities that restricted access to this dream for many Americans. As a result, the American Dream began to lose its credibility, particularly as other nations witnessed the disparities and contradictions within the United States itself.

Unintended Consequences in the Middle East and Beyond

In the Middle East, the American Dream and Western ideals clashed significantly with local values, creating both fascination and hostility. As the U.S. became more involved in the region’s politics and economy, particularly in the wake of oil discoveries, American interests often conflicted with local customs, religions, and societal norms. The promotion of Western values such as secularism, individualism, and consumerism was frequently perceived as a threat to traditional ways of life, sparking resentment among those who saw the American influence as eroding their cultural identity.

American intervention in the Middle East during the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century also led to political instability and economic dependence in many countries. In Iran, for instance, the U.S.-backed overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953 and support for the autocratic Shah led to deep-rooted resentment among Iranians, who viewed America’s involvement as an imposition on their sovereignty. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was, in part, a reaction against perceived American interference, with the new government condemning Western influence as a threat to Islamic values and self-determination.

Similarly, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, launched in the name of promoting democracy and freedom, intensified anti-American sentiment. For many in these regions, the American military presence represented not liberation but occupation. The disillusionment with Western ideals was compounded by the destruction, displacement, and instability caused by these conflicts. As writer Edward Said noted in Orientalism, “the West’s vision of the East is always filtered through the lens of power and control,” a dynamic that has fueled resentment and distrust.

The Legacy of Economic Influence and Cultural Imperialism

Beyond direct military intervention, the economic influence of the U.S. also contributed to resentment. American corporations expanded aggressively in the postwar era, bringing Western consumerism and capitalist values to regions unaccustomed to such systems. In places like Latin America and Southeast Asia, American corporations gained control over local resources, sometimes with the support of U.S. government policies that prioritized economic interests over local sovereignty. The economic dependency created by these corporations often stifled local economies, fostering resentment toward both American businesses and the Western ideals of capitalism they represented.

Moreover, the export of Western media, Hollywood films, American television shows, and consumer advertisements, reinforced the image of the American Dream, portraying an idealized version of the West that was difficult for many to reconcile with the realities of their own lives. This cultural influence, often labeled as “cultural imperialism,” created an expectation of Western prosperity and modernity that was neither universally attainable nor entirely welcomed. For many, particularly in conservative societies, the spread of Western media was seen as an attempt to impose foreign values and erode cultural traditions. This sense of cultural imposition has been a significant factor in the backlash against Western ideals in various parts of the world.

Broken Promises and Global Disillusionment

The resentment towards the American Dream and Western ideals has been compounded by the perception that these promises are empty or hypocritical. In many cases, the same freedoms that are promoted internationally are not fully realized within the United States itself. The disparities in wealth, racial inequality, and social justice issues have shown that the American Dream is not accessible to all Americans, which has damaged the credibility of promoting such ideals abroad.

In recent years, the rise of anti-American sentiment has highlighted the global disillusionment with the myth of the West. In regions affected by economic and political interventions, the American Dream has come to represent broken promises, rather than hope and freedom. For many, the Western ideal has proven to be exclusionary, benefiting only a privileged few while leaving others with economic hardship, cultural disruption, and political instability.

The Western Dream as a Source of Admiration and Resentment

The Western myth continues to inspire and draw admiration, yet it also remains a source of resentment for those who feel that it has imposed unrealistic expectations or destabilized their societies. This duality reflects the contradictions inherent in the myth of the West: while it promotes ideals of freedom and opportunity, it has often been used as a tool of economic and cultural domination. The legacy of this broken promise is complex, fueling both fascination with and opposition to American influence around the world.

As the world grapples with issues of globalization, cultural identity, and power dynamics, the myth of the West serves as both an aspirational ideal and a cautionary tale. For those who continue to seek the freedom and prosperity it promises, the myth offers hope; for others, especially those in regions affected by American intervention, it represents a betrayal. In this way, the Western dream remains an influential yet deeply contested idea, one whose impact is felt far beyond the borders of the American West.

Silicon Valley and the New Western Utopia

In the 21st century, Silicon Valley has come to represent a new iteration of the Western utopia, a place of innovation, boundless potential, and radical reinvention. Just as the American West once symbolized opportunity and the promise of a new life, Silicon Valley has become synonymous with the idea that technology can reshape the world for the better. The region is celebrated as a frontier of human ingenuity, where individuals can push the limits of what’s possible and build futures defined by progress and possibility. However, Silicon Valley has also inherited many of the challenges and contradictions of the traditional Western myth, from inequality and exploitation to environmental impact, revealing that the new digital utopia is subject to many of the same flaws that plagued the original Western dream.

The Digital Frontier: Innovation, Opportunity, and the American Dream

Silicon Valley is often described in terms that echo the language of the frontier. Entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and tech workers are framed as pioneers exploring new territory, armed not with guns and wagons, but with algorithms, venture capital, and visionary ideas. Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, famously called his products “bicycles for the mind,” promoting the idea that technology could liberate and empower individuals, much like the West was once seen as a place of freedom and personal agency. This vision resonates deeply with the American Dream, transforming Silicon Valley into a space where innovation is celebrated as a form of self-fulfillment and reinvention.

In many ways, Silicon Valley embodies the Western myth of opportunity. The stories of tech giants like Apple, Google, and Facebook reinforce the idea that anyone with a good idea, determination, and access to capital can succeed. The region is filled with narratives of college dropouts turned billionaires, immigrants who found success through hard work, and ambitious individuals who transformed their lives through technology. This promise of reinvention and success aligns with the Western ideal that one’s destiny is not predetermined but can be shaped by vision and perseverance.

Economic Inequality and the Broken Promises of the Tech Utopia

However, like the myth of the West, Silicon Valley’s utopian vision masks significant inequalities and contradictions. The wealth generated in Silicon Valley is concentrated among a small group of individuals and corporations, creating economic disparities that parallel the boom-and-bust cycles of earlier Western expansions. For every successful entrepreneur, there are thousands of workers who struggle with precarious employment, high housing costs, and limited job security. The median home price in San Francisco and surrounding areas has soared in recent decades, with typical home prices exceeding $1 million, making it nearly impossible for middle- and low-income workers to live in the communities where they work.

Tech companies have often promoted themselves as meritocratic, claiming that talent and hard work are the sole determinants of success. Yet, studies have shown that Silicon Valley’s workforce lacks diversity, with a significant underrepresentation of women and minorities in leadership positions. Reports on tech culture have highlighted patterns of exclusion and discrimination, revealing a gap between the ideal of meritocracy and the reality of structural inequality. In this way, Silicon Valley’s promise of equal opportunity mirrors the unfulfilled promises of the American Dream, where systemic barriers prevent true equity.

Environmental Impact and the Illusion of Digital Sustainability

The promise of Silicon Valley as a utopia also extends to its vision of a sustainable, digitally connected world. Tech companies have frequently promoted the idea that innovation can solve environmental problems, investing in renewable energy and promoting a “green” digital economy. Companies like Google and Apple have made strides in powering their data centers with renewable energy, framing themselves as leaders in the movement for a sustainable future.

Yet the digital utopia promoted by Silicon Valley has its own environmental costs. Data centers consume vast amounts of electricity, and the production of electronic devices involves the extraction of rare minerals and the generation of toxic waste. E-waste, generated by discarded phones, laptops, and tablets, has become a global issue, with millions of tons of electronic waste exported to developing countries each year. In many cases, local communities in these countries suffer the environmental and health consequences of processing this waste, while Silicon Valley companies continue to promote the illusion of clean, digital progress.

The environmental costs of Silicon Valley’s tech utopia reflect a broader theme in the Western myth: the idea that human innovation and expansion often come at the expense of sustainability and ecological balance. Just as Western expansion led to the depletion of natural resources and degradation of the landscape, Silicon Valley’s reliance on digital infrastructure has brought about a new form of environmental exploitation, challenging the notion that technology alone can create a sustainable future.

Surveillance, Data Privacy, and the Loss of Personal Freedom

One of the most significant contradictions in Silicon Valley’s utopian vision is its impact on personal freedom and privacy. While tech companies have promoted their products as tools for empowerment and self-expression, many have come under scrutiny for practices that compromise user privacy and increase corporate surveillance. Companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon have amassed vast amounts of data on users, raising concerns about how this information is collected, stored, and used.

In the Western myth, freedom was a central value, the West was seen as a place where individuals could escape from societal constraints and build lives on their own terms. In Silicon Valley’s digital utopia, however, users often sacrifice privacy and autonomy in exchange for convenience and connectivity. Social media platforms and search engines collect and analyze user data to target advertisements, shape user experiences, and, in some cases, influence behavior. As author Shoshana Zuboff discusses in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Silicon Valley’s data-driven economy operates through a system of “surveillance capitalism,” where user information is commodified for profit, challenging the idea of personal freedom in the digital age.

This erosion of privacy and autonomy reveals a fundamental tension within Silicon Valley’s utopia: while technology is marketed as a tool for liberation, it also creates new forms of control and dependency. The West was once a place of escape; Silicon Valley’s digital frontier, in contrast, has created a system where individuals are constantly monitored, influenced, and commodified.

The Disillusionment of the New Western Utopia

Today, Silicon Valley’s utopian ideals are increasingly questioned. Rising economic inequality, environmental concerns, and privacy issues have led to a wave of skepticism about the tech industry’s promises. Critics argue that Silicon Valley has become a place where profits and data take precedence over genuine human connection and societal well-being. Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of Theranos, became a symbol of Silicon Valley’s darker side when her blood-testing startup was exposed as a fraud, underscoring the high-stakes ambition and relentless pursuit of success that often prioritize image over substance.

This disillusionment reflects a broader sense of disappointment with the Western utopia Silicon Valley represents. The region’s promises of empowerment, progress, and freedom are increasingly viewed as exclusive, benefiting a small elite while creating systemic inequalities and ethical dilemmas. Silicon Valley, like the American West, has shown that even the most promising frontiers can become sites of broken dreams, revealing the limits of a utopia that prioritizes innovation and profit over community and sustainability.

Silicon Valley as the New Frontier, and the New Myth

Silicon Valley’s story is still unfolding, but it has already left a profound impact on the myth of the West. Just as the American frontier once symbolized freedom and opportunity, Silicon Valley has come to represent a new frontier of digital possibility, where people can reimagine their lives through technology. Yet, like the Western pioneers before them, Silicon Valley’s tech giants have also been accused of exploiting resources, excluding certain communities, and creating a society where only a privileged few can realize the dream.

As Silicon Valley continues to shape the future, its legacy will likely reflect both the aspirational and the cautionary aspects of the Western myth. The digital utopia it promises is both alluring and deeply flawed, a modern echo of the promises and pitfalls that have characterized the American West for centuries. In this way, Silicon Valley is not only a new frontier but also a reminder of the enduring contradictions that lie at the heart of the Western dream.

The “American Dream” and Western Disillusionment

The concept of the American Dream is intrinsically tied to the myth of the West. It embodies the ideals of freedom, opportunity, and prosperity, the belief that anyone, regardless of their background, can achieve success through hard work and determination. Since its origins, the American Dream has captivated people within the United States and around the world, presenting the West as a place of reinvention and upward mobility. Yet, as economic and social inequalities continue to grow, the American Dream has become increasingly elusive for many, fostering a sense of disillusionment that challenges the utopian vision once associated with the West.

Origins of the American Dream and Its Western Roots

The American Dream, as a formalized concept, was popularized by historian and writer James Truslow Adams in his 1931 book The Epic of America. Adams defined it as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.” This vision drew heavily from the legacy of the Western frontier, where the ideals of individualism, self-reliance, and limitless potential had taken root. For settlers and pioneers, the West represented a new beginning, a chance to escape the restrictions of Eastern society and forge a life based on merit and hard work.

The American Dream’s appeal lay in its inclusivity and optimism. It suggested that class, ethnicity, and social status would not define one’s destiny in America; instead, character, ambition, and perseverance were the key determinants of success. This belief became a cornerstone of American identity, shaping not only national policies but also popular culture. Western films, novels, and advertisements promoted the ideal of the self-made individual, cementing the notion that success was accessible to anyone willing to put in the effort. For many, the West was synonymous with this dream, a place where opportunity awaited those bold enough to pursue it.

Economic Inequality and the Fraying of the American Dream