The 1901 Census website was meant to showcase British digitisation, but instead it became a punchline: servers that buckled on launch, mismatched kit lashed together, prisoner-typed data laced with obscenities, and retired “10 till 3 grannies” and neurodiverse consultants cleaning up the mess. I was called in to write the report that unravelled the fiasco, a job that took me from QinetiQ’s “Santa in tweed” CTO to the Cabinet Office, where I first crossed paths with Alan Mather, and learned hard lessons about hubris, engineering, and failure, along the way.

Contents

Introduction

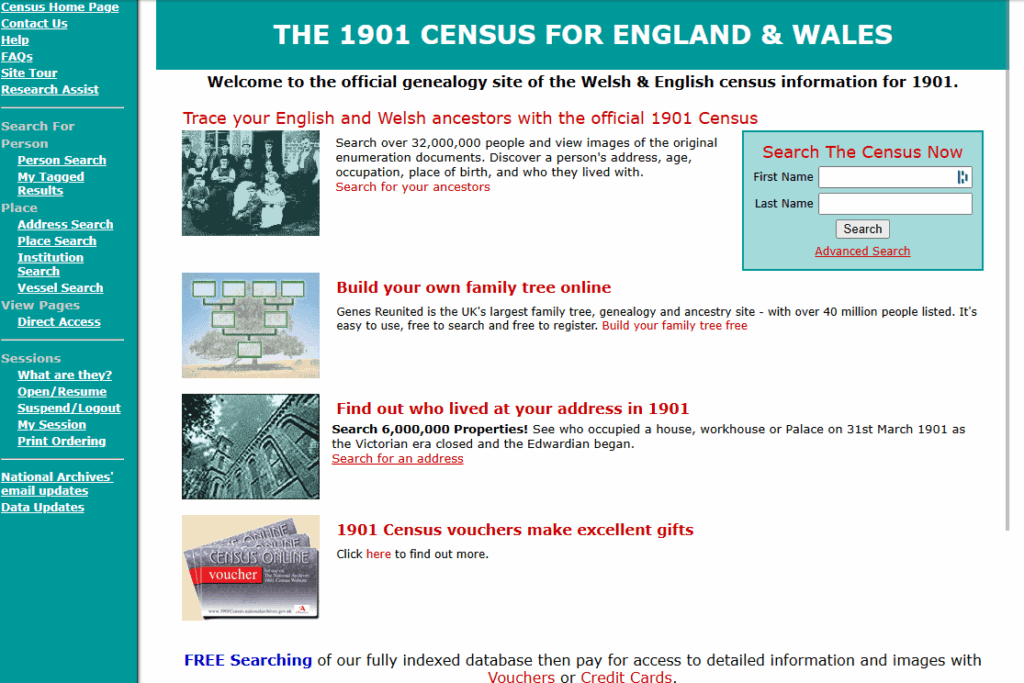

When the 1901 Census went online, it should have been a triumph, the nation’s archive made accessible to millions. Instead, it collapsed in a mess of outages, mismatched servers, and a digitisation process so badly thought through that it became the stuff of satire. My hero Juvenal would have been proud.

It became infamous. The Register and The Inquirer tore into it gleefully, and rightly so. But behind the headlines was a serious mess, and my job was to walk into it, pick it apart, and write the report that explained why it had collapsed.

The Punk IT Press Smelled Blood

Before I was involved, the Register and Inquirer were already circling. They were at their peak in the early 2000s, punk in tone, gleefully hostile to bullshit, unafraid to call civil servants, big business, and contractors out by name.

Mike Magee, John Lettice, and the rest didn’t mince words. The Register and The Inquirer at that point were punk in every sense, rough-edged, gleefully hostile to bullshit, and more than willing to name names. Magee was the godfather of that style: DIY newsprint ethos translated into the web, a kind of gonzo, tabloid-punk hybrid that took no prisoners. Lettice had the sharp analytical eye that skewered policy pretence with one line. Together, they made government IT look absurd, not because they exaggerated, but because they printed it straight. They painted the census site as not just a failure of infrastructure, but a failure of culture: the British state trying to do “digital” and producing farce. And sadly, they weren’t wrong.

Failings Piled High

My job was to capture all of this in black and white. QinetiQ and the PRO wanted a formal report, not pub anecdotes; they had hard questions for Sun, who’d supplied the kit. So off I trotted to Malvern and the new QinetiQ office/old DERA facility, as QinetiQ had just been spun out of DERA. I spent a few days on site, checking out the servers, looking at documentation, and interviewing key staff. I wrote it down, stripped of colour: the architecture mistakes, the procurement failures, the design flaws that made collapse inevitable. What follows is the sort of thing you’d find in that report: blunt, technical, clinical.

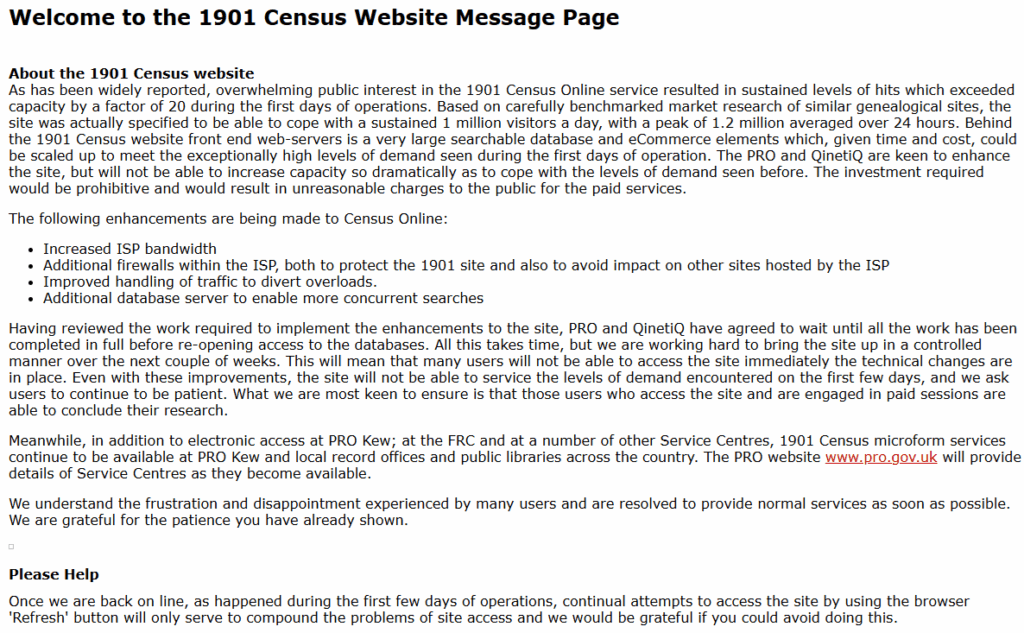

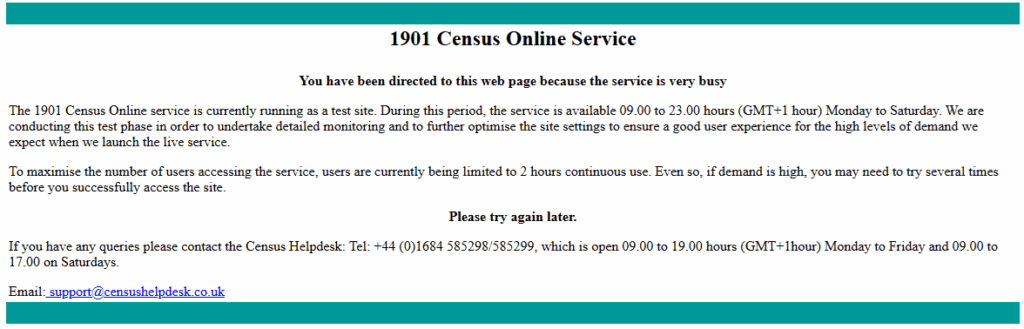

Unprepared for Load

The census site was hammered on launch. Anyone who knew genealogy could have told them the Americans would flood in. Family history is a national obsession over there, with big communities of amateur genealogists who had been waiting for these records. Instead of planning for that, the architecture was built like it was serving a parish newsletter. It folded within hours.

Grey-Market Procurement

Some of the kit had come in through the grey market, bought on the cheap, not spec’ed correctly, shoved into racks, and expected to carry a national system. It was penny-wise, pound-foolish procurement. It saved money on paper but cost far more in failure. That bargain hunting is how they ended up bolting a cheap, newer 1280 onto an older M8000 and calling it a cluster.

Bad Clustering

The hardware setup was farcical. This wasn’t just “bad clustering”; it was an Oracle database cluster doomed from the outset. The original anchor node was a Sun Fire M8000, part of that Cray-influenced midframe line: big, expensive, architected like a mini-mainframe. Incidentally bought from the grey market to save precious pennies (more on that later). After the crash, they rang Sun, bought and bolted on a Sun Fire 1280, a newer, cheaper box that, thanks to Moore’s Law and tasty Intel chips, could actually push more load than the older beast. In theory, you might balance that out; in practice, they never had a chance.

The OS versions and patch levels weren’t even in sync between the two machines. Oracle RAC (“Real Application Cluster”) expects near-identical nodes with matched firmware, storage paths, and interconnects. What they built was a Frankenstein cluster: asymmetric hardware, divergent OS stacks, inconsistent drivers. Failover didn’t just wobble; it never worked at all. Sessions died in waves, the cluster thrashed, and resilience was a fantasy. You can’t glue different generations of kit together, run mismatched Solaris builds, and expect Oracle not to notice. It notices. And half of the web and app servers were pointed at this node. It was an embarrassment of architecture.

Poor Architecture

The deeper flaw wasn’t just bad procurement or mismatched kit; it was architectural hubris. The design assumed that clustering alone would save them, without any serious modelling of traffic, load, or failure paths. Resilience was treated as a box-ticking exercise, “put two servers together and call it fault-tolerant”, rather than a discipline of planning for the unexpected.

There was no serious capacity modelling, no soak testing, no attempt to replicate real-world genealogy demand. Worse, the architecture had no layered defence: if the database cluster failed, the whole site failed. A single subsystem collapse cascaded instantly because there was no proper separation of concerns, no decoupling, and no queues to buffer or shed load.

That’s what I mean by hubris. The assumption that the cleverest bit of tech, Oracle RAC, shiny Sun kit, would paper over the cracks in planning. Architecture isn’t a diagram you present to a steering board; it’s the discipline of asking “what happens when this falls over?” and building something that degrades gracefully. On the census site, nothing degraded gracefully. It just collapsed.

In fairness, QinetiQ were only one piece of the jigsaw. The PRO’s procurement choices, budget blowouts, and lack of commercial nous shaped the constraints they were working under. The architecture failed, but the governance failed first.

PRO Budget Misfire

A big part of why the kit procurement was such a dog’s breakfast came down to the PRO (the “Public Record Office”). They’d already blown a huge chunk of the budget on retranscribing the microfiche, an expensive exercise in make-work that should never have been necessary. By the time it came to actually building the infrastructure, the money left was thin. Corners were cut, grey-market kit was dragged in, and the system was lashed together with whatever they could afford. The dumb decisions weren’t random; they were the fallout from a budget that had already been pissed away upstream.

Poor Governance

At root, the census site collapsed because governance was missing in action. The PRO commissioned the work but never set up a structure to manage risk at this scale. QinetiQ were handed the build but were new to public web projects. Sun were in the frame but not in the room when the critical decisions were made.

No single body owned delivery end-to-end. Procurement, design, and operations were fragmented across silos, each making tactical decisions without a shared map of risk. That’s how you ended up with mismatched hardware, grey-market kit, a naïve commercial model, and a transcription process that went from prisoners to pensioners.

It’s tempting to pin the blame on QinetiQ or the PRO alone, but the truth is that governance failed first. With strong oversight, those architectural mistakes would never have made it out of design. Without it, they cascaded in production.

Outside the Report: What Made it Worse

Of course, the report could only cover the hard failures, the measurable stuff. But there was plenty outside the report too: cultural blind spots, institutional arrogance, and plain absurdity. These didn’t sit neatly in a risk register, but they made the whole fiasco far worse.

Ireland Showed Us Up

What made it sting even more was the comparison across the Irish Sea. Around the same time, Ireland put their census online and made it free. No drama, no headlines, no charging model. Just: here it is, JFDI, happy days. Civil servants I spoke to shrugged it off: “Well, more people will want ours”. Really? Have you been to America? It’s full of people tracing their Irish roots. The arrogance of the British elite was laid bare, where Ireland had delivered quietly and for free, England wrapped itself in cost-recovery schemes and excuses, and got humiliation instead.

Defence DNA and Old Habits

QinetiQ had only just spun out of DERA, the old Defence Evaluation and Research Agency. They were brilliant at defence research, but brand new to building public-facing web infrastructure. The culture was still steeped in defence habits, hierarchical, insular, experimental. It wasn’t malice; it was a mismatch. And in some ways, it echoed an older pattern in British science and engineering: Barnes Wallis, tolerated when useful, then sidelined; Tommy Flowers, whose Colossus was buried in secrecy while the spotlight fell on Turing. Time and again, inconvenient brilliance was played down or mishandled. Handing a national census website to a newly commercialised defence lab was another turn of the wheel, not arrogance so much as a kind of institutional blindness, repeating the habit of putting the wrong people on the right problem.

Prisoners Doing the Transcribing

Then there was the data. To digitise the census records, they used prison labour. On one level, logical: lots of typing, cheap workforce. But nobody asked what would happen if the prisoners got bored. And of course they did.

They realised they could slip swear words into the records. Suddenly, the national census was peppered with obscenities. Imagine being a family historian, logging in to see your great-grandfather’s record, only to find his occupation listed as “wanker.”

It was absurd. It was predictable. And it was symptomatic of the whole project: nobody thought it through.

“10 Till 3 Grannies”

The fix for the prisoner fiasco was equally surreal. They hired retirees, often older women working short shifts, ten till three, correcting the errors the prisoners had left behind. I called them the “10 till 3 grannies.”

That nickname wasn’t plucked out of thin air. My first proper out-of-school job was at Lloyds Bank, where I spent days leafing through banknotes as a “foreign money forgery expert”. You don’t really look at the notes, you feel them; forgery recognition is tactile. But often the real pressure was reconciliation, and to get it done on time, the bank would bring in older women, late forties through to their sixties, working short shifts. They came in at ten, left at three, and they kept the whole process ticking over. I called them the “10 till 3 grannies” back then too, so when the same dynamic reappeared in the census fiasco, the name stuck instantly.

So now, instead of a streamlined digitisation effort, you had a bizarre production line: prisoners putting in the swears, grannies cleaning them up. It would have been funny if it weren’t the national archive.

Commercial Naivety: Government Cost Centres vs Profit Centres

Part of the dysfunction came from a deeper problem: government cost centres trying to reinvent themselves as profit centres. The PRO thought it could fund the census site by charging users; QinetiQ, newly spun out from DERA, bought into that logic. But government departments aren’t built for commerce. The Home Office tried the same with the “golden visa” scheme for wealthy Chinese applicants; it raked in cash but had no machinery to manage the money wisely. Police forces dabbled with speed-camera revenues and ended up accused of being tax collectors rather than peacekeepers. These ventures stumble because the DNA of the organisation is service and accountability, not profit. In the case of the census, commercial naivety led to over-promising and under-delivering, and the public paid the price.

Meeting “Santa in Tweed”

After they had successfully implemented my recommendations, and I have a gift of turning the surreally complicated into paint-by-numbers noddyiness, boiling it all down into baby steps so even the most reluctant exec could follow along, so they hauled me back in to meet the big man, down into a bunker at the old DERA site. In shuffles the CTO of QinetiQ, Santa in a tweed jacket: big beard, pipe, straight out of a 1940s newsreel. I was granted a twenty-minute audience, because of course he was Very Important and I was “just the consultant who wipes their arse”, right?

We sit. I run through the architecture, the mismatched kit, the non-trivial limits they’d blithely ignored. Then I said, as evenly as I could: “Frankly, it feels like the first website you’ve ever built”. He replies, laconic as you like: “Yes. It is”.

That’s the bit that floored me. This wasn’t a parish noticeboard; it was the UK census, national pride and global visibility, American genealogy traffic by the truckload, orders of magnitude they’d never modelled. It was technocratic hubris welded to first-flight naïveté. You don’t choose the nation’s census as your training wheels. You just don’t.

I guess QinetiQ have had a special place in my heart ever since, and to be fair, I’ve worked with QinetiQ plenty of times after that, and seen their best side. When I was Chief Architect and Head of Infrastructure at Thomas Cook Online, they handled our penetration testing professionally, rigorously, and with the confidence you’d expect from a firm with deep defence roots. The census project showed their growing pains, but not their ceiling.

First Meeting with Alan Mather

The report landed at the Cabinet Office. That’s where I first met Alan Mather. Alan had been told his team had “fixed the census site.” I slid the report across the table and said, as politely as I could, that it explained exactly how it had been fixed, and that it hadn’t been magic, it had been engineering.

That meeting mattered. Alan didn’t flinch. He read it, asked the right questions, and, crucially, he kept me close. From that day forward, he was both sponsor and ally, pulling me into projects where his backing meant I could actually get things done.

Alan had this rare ability to tell who in the room was worth listening to. It reminded me of the old Scrum analogy of pigs and chickens. In the fable, a pig and a chicken decide to open a restaurant. The chicken suggests calling it “Ham and Eggs.” The pig declines, because the chicken is just involved, but the pig is committed. The chicken can flap, but the pig pays with its skin.

In government IT, and IT everywhere really, the room is always full of chickens: noise without risk. Alan had the gift of knowing who the pigs were, the ones truly committed, the ones who would bleed to make something work. He could cut through the theatre, the endless PowerPoint, and spot who was actually serving the project and who was just serving themselves.

That was the start of a professional relationship and a friendship that shaped the next decade of my career. Without Alan’s support, I wouldn’t have ended up redesigning the UK border control system, chasing down firewall policies on the Government Gateway, or building the Sun/Software AG DIS “box”. The census fiasco was our introduction; everything that followed built on the trust forged in that first meeting.

The NAO Whitewash

Towards the end of the debacle, the National Audit Office weighed in with its own report. The conclusion? That the site had simply been overwhelmed by unexpected demand, fuelled by too much press coverage. True enough, traffic was heavy, but the framing was a whitewash. It glossed over structural failures that were blindingly obvious: handing a load-bearing national project to a team that had never built one before; relying on prisoners for transcription without fair pay, structure, or dignity; and then having to re-procure when the inevitable happened. Years later, the data quality was still in question. Reducing it all to “too many Americans clicking refresh” misses the point. The failure wasn’t just about traffic; it was about bad choices, weak governance, and a refusal to own the mistakes.

Lessons from the Census Fiasco

What the census taught me was blunt:

- Don’t give mission-critical projects to teams on their first website.

- Don’t lash mismatched hardware together and call it a cluster.

- Don’t underestimate demand just because it’s “only history.”

- Don’t chase procurement savings that collapse in production.

- Don’t use prisoners to type up your nation’s heritage.

But it also confirmed why I thrive on “nasty projects.” Because when it’s all gone wrong, you cut through the theatre. You measure, diagnose, fix, and you stay until it works. That’s the art, that’s the craft; engineering as compulsion, Autism gone awry.

Conclusion

The 1901 census site became infamous: the website that swore at grannies, collapsed on launch, and made international headlines. In the end, private genealogy sites like Genes Reunited succeeded where the state had fumbled, another lesson in what happens when government tries to graft commercial logic onto civic infrastructure without the culture to sustain it.

For me, it was also formative. It introduced me to Alan Mather. It gave me stories that still make me laugh. And it proved again that failure often teaches more than success. It was absurd, frustrating, and sometimes hilarious. But out of the mess came lessons and opportunities that shaped the rest of my career.

References

2002 Articles

- 02 Jan 2002 — Brits flock to 1901 census site — launch day enthusiasm

- 03 Jan 2002 — 1901 Census site closed for urgent repairs — shutdown within 48 hours

- 08 Jan 2002 — Census site shuts for a week — the first of many pauses

- 16 Jan 2002 — Census site stays offline — down

- 05 Feb 2002 — UK census site stays shut — still down

- 05 Mar 2002 — 1901 Census farce runs and runs — not up yet

- 03 Jul 2002 — 1901 Census site still down after six months — nope

- 25 Jul 2002 — 1901 Census site update is no update — hide!

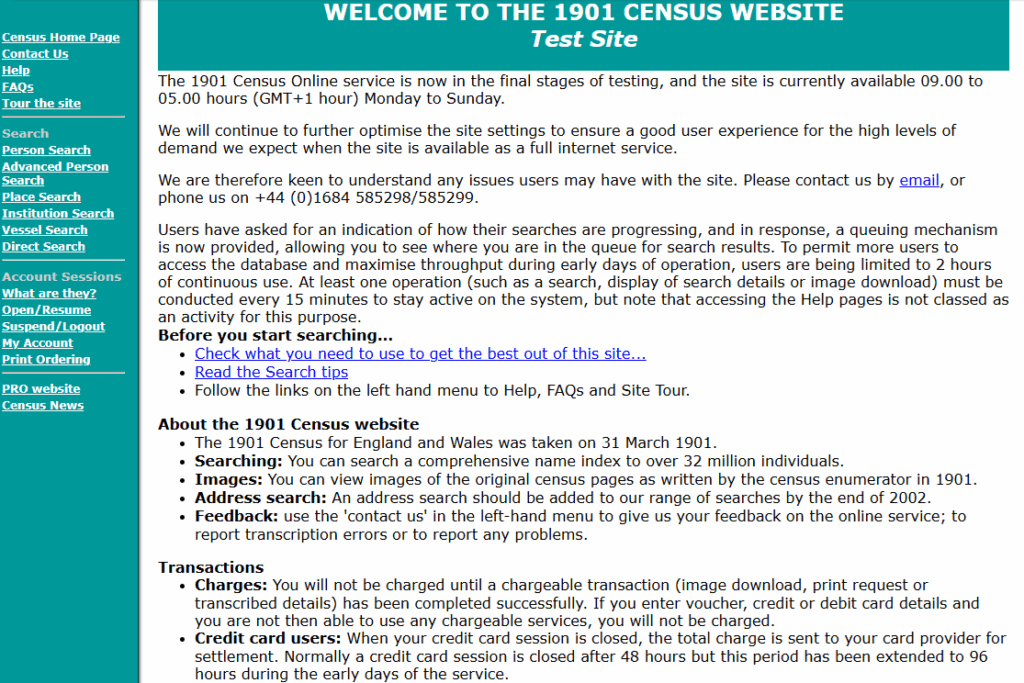

- 29 Aug 2002 — 1901 Census available online for testing — partial reopening, still shaky

- 15 Nov 2002 — Could you be descended from a Shagger? — prisoner data errors hit the headlines

2003 Articles

- 14 Nov 2003 — Media, people blamed for 1901 census site cock-up — belated official blame-shifting, when in doubt blame the lusers lol