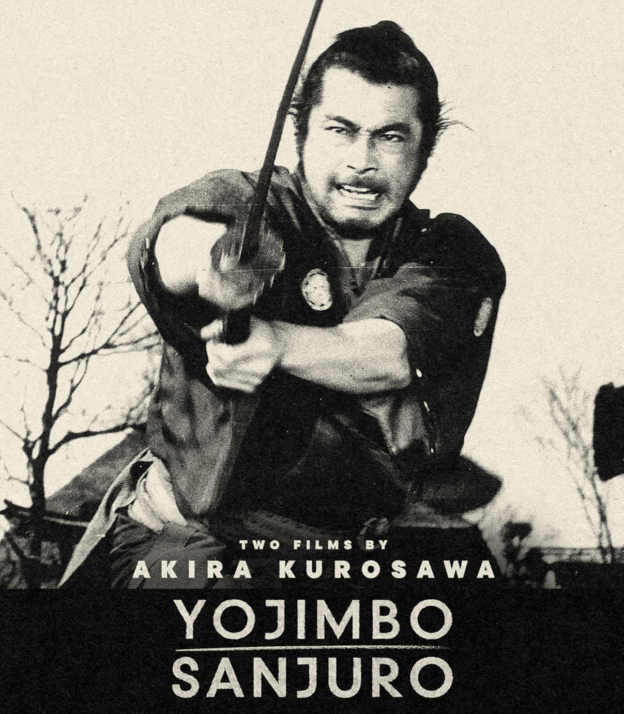

This article explores Yojimbo and Sanjuro as two sides of the same coin, charting the decline of the samurai in feudal Japan. Yojimbo depicts the “why”: the collapse brought on by greed, corruption, and the rise of firearms, where mediocre men with guns en masse overpower disciplined swordsmen. Sanjuro shows the “how”, the aftermath, where the last true samurai are left to kill each other while naive reformers blunder around them. Together, the films reflect Kurosawa’s shifting mood and Japan’s uncertain transition into modernity.

Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962) are often discussed as companion pieces, or even casual sequels. But this framing misses their real power. They are not merely two stories featuring the same wandering swordsman. Together, they form a profound diptych on the death of the samurai and the decay of feudal Japan, seen through different lenses. One is the why of collapse, the other is the how. Together, they chronicle the end of an age and the psychological toll of those forced to survive it.

Context: Kurosawa’s Mood, Japan’s Mirror

When Kurosawa made Yojimbo, he was in a state of quiet rebellion. Disillusioned by politics, weary of studio interference, and wary of Japan’s growing Westernisation, he channelled his frustration into a film that satirised power, mocked the preening pretenders of authority, and gleefully tore down the myth of honourable samurai.

By Sanjuro, his mood had shifted. The film is funnier, more ironic, and more self-aware. But it is also tinged with fatigue. The violence is no longer revolutionary… it is ritualistic. The lone hero who outwits corrupt warlords is now stuck among bumbling idealists, trying to restrain their eagerness for blood. Kurosawa was at once amused by their naïveté and sorrowful about what had been lost. Japan was entering its post-war economic boom, and the director, now in his fifties, saw an older world fading before his eyes.

Yojimbo: The Collapse Begins

At face value, Yojimbo is a stylish, sardonic film about a nameless ronin who arrives in a town riven by two rival gangs. He plays them off each other and walks away after a trail of destruction, having liberated the townspeople by way of manipulation and murder.

But this is no simple Western (even though it influenced A Fistful of Dollars). It’s a story about the end of traditional power. The samurai is no longer bound to a master. The daimyos are reduced to scheming thugs. Honour is dead. The sword is slowly becoming obsolete.

The clearest symbol of this is the gun, smuggled in by the corrupt Unosuke. It is the first meaningful firearm in Kurosawa’s samurai films, and its presence changes the rules. The ronin must outwit it rather than confront it head-on. This gun represents Western influence, the dismantling of bushido, and the looming industrialisation of violence. What the sword once settled, the bullet now interrupts.

In Yojimbo, Kurosawa shows us the death of the old codes. He is not sentimental about it. His protagonist is ruthless, cunning, and cynical. But there’s still a sense of mourning. The age of samurai ends not with honour, but with petty thuggery and foreign steel.

Sanjuro: What Comes After

Sanjuro opens with a gag: a group of idealistic young men debating how to reform their corrupt clan. They are earnest, clumsy, and completely out of their depth. Into their midst wanders the same ronin, now more sardonic, more weary. He saves them not through idealism, but through guile and violence. He mocks their naivety, yet protects them.

Where Yojimbo is a howl of destruction, Sanjuro is the slow settling of the ash. The central antagonist, Hanbei Muroto, is not a brutish warlord. He is a version of the ronin himself: disciplined, intelligent, equally displaced by a changing world. Their final duel is almost an act of mutual recognition. They are what remains of a warrior class that no longer has a role.

Despite the film’s comedic tone, its ending is colder and sadder than Yojimbo. After all the wry humour, Sanjuro finds himself once again alone. He spares no glory for his actions. He dismisses the thanks of those he saved. Even the brutal final sword strike, infamously explosive, is not triumph, but grief. He walks away not because he’s free, but because there’s nowhere left to go. His equal, in terms of sword craft, is dead; the world of the Samurai is over.

Influences: What Formed and Followed Them

Both films are shaped by a confluence of Japanese and Western influences. Kurosawa was deeply inspired by American cinema, particularly John Ford, and by the hard-boiled fiction of Dashiell Hammett (Yojimbo was partly based on Red Harvest). Yet he rooted these stories in a distinctly Japanese reckoning with modernity and historical memory.

In return, these films reshaped cinema. Yojimbo directly inspired Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, launching the spaghetti western genre. Its visual language, the wide framing, sudden violence, and the wry antihero would ripple through filmmakers from Scorsese to Tarantino. Sanjuro is quieter in its legacy, but its humour, choreography, and tone influenced later Japanese directors grappling with post-samurai identity, including Takeshi Kitano and Hirokazu Kore-eda.

Two Sides of the Same Coin

If Yojimbo is the explanation, the why of the collapse, Sanjuro is the fallout, the how. One tears down, the other sifts through the rubble.

In Yojimbo, we see a once-noble warrior class corroded by greed and external influence, now forced to confront a new world where mediocrities armed with firearms can overpower the skilled and disciplined samurai. It is a battle they can no longer win, not because they lack courage or honour, but because the rules of warfare have changed.

In Sanjuro, we see the last remnants of that class, unsure whether to keep fighting, to guide, or to disappear, sidelined and displaced, they are forced into duels with one another while the bumbling idiots of modernity slapstick around them, oblivious to the meaning of what is dying in front of them.

In Yojimbo, we see a once-noble warrior class corroded by greed and external influence. In Sanjuro, we see the last remnants of that class, unsure whether to keep fighting, to guide, or to disappear.

Both films feature the same wandering figure. But where Yojimbo’s ronin is a destroyer, cutting down the corrupt in a town that deserves to fall, Sanjuro’s is almost paternal. He wants to save the next generation from his cynicism. He keeps telling the young samurai not to draw their swords so quickly. He knows what comes of that path. He’s lived it.

And while Sanjuro appears lighter in tone, it leaves us with a darker truth. There is no future for men like him. The age of the samurai is over.

Final Reflections

Taken together, Yojimbo and Sanjuro are not simply action films or satires. They are a reckoning. They show us what is lost when a civilisation discards its moral codes, and what confusion remains when those codes are gone.

Kurosawa understood the pain of collapse and the emptiness of survival. Yojimbo offers catharsis through fire. Sanjuro offers no such release. It leaves us with a swordsman who walks away, not victorious, but unmoored.

These films don’t just chart the end of the samurai. They mourn it.