This article delves into the uncharted territories of human survival, morality, and existential dread through a comparative analysis of Warlock by Oakley Hall, Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, the film Sorcerer, and Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me by Richard Fariña. Although set in vastly different landscapes and eras, from the lawless American West to the countercultural 1960s and the brutal South American jungle, these works converge on themes of rebellion, chaos, and the limits of human endurance. Through shared influences and resonant themes, this article unravels how each narrative confronts the human struggle for meaning in worlds that seem determined to thwart it.

Introduction: Lawlessness, Survival, and the Quest for Meaning

American literature and cinema often delve into the themes of lawlessness, existential survival, and human morality against harsh, unforgiving landscapes. These themes intersect in the works of Warlock by Oakley Hall, Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, the film Sorcerer (based on Georges Arnaud’s novel Le Salaire de la Peur), and Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me by Richard Fariña. Despite their diverse settings, ranging from the Old West to post-colonial jungles and the countercultural revolution, they share a common thread of existential questioning and a critique of power structures.

This article was inspired by conversations with my son, Bill, during his time at the University of Birmingham, on his degree course in English Literature. This particular article leads into, and acts as a precursor, to my “Myth of the West” cycle.

Warlock: Oakley Hall’s Complex Vision of Justice and Order

Set in the American West during the late 19th century, Warlock is an intricate examination of justice, law, and power within a small frontier town. Hall’s novel centres on the figure of Clay Blaisedell, a gunslinger hired to bring order to the town of Warlock. What begins as a straightforward tale of justice spirals into a narrative about the moral ambiguity of authority and the fragility of law. The town’s desperate attempt to impose order only highlights the inherent chaos of frontier life, raising questions about whether law is a human construct meant to create order or an arbitrary force that perpetuates violence.

Hall’s vision of the West is one of complexity, blending mythical heroism with psychological depth. The gunslinger, a classic trope of Westerns, is depicted not as a romanticised figure but as one plagued by doubt and futility. This is not the West of clear moral codes; it is a West of fragile power, where heroism is indistinguishable from tyranny, and peace is fleeting. Warlock interrogates the very fabric of Western mythology, casting doubt on the legitimacy of both individual and institutional authority.

Blood Meridian: Cormac McCarthy’s Nihilistic Frontier

McCarthy’s Blood Meridian takes the Western genre even further, plunging it into a nihilistic abyss where violence becomes a primal, elemental force. Set in the mid-19th century, the novel follows a nameless protagonist, “the Kid,” as he joins a scalp-hunting expedition led by the enigmatic and terrifying Judge Holden. The novel’s landscapes, vast deserts and mountains, are harsh and indifferent, reflecting the lawlessness that pervades every human interaction.

Where Warlock grapples with the failure of order and justice, Blood Meridian discards these concepts entirely. McCarthy’s world is one without morality, where violence is not a means to an end but an inherent part of existence. Judge Holden, who embodies this worldview, is a figure of almost mythic evil, philosophising that war is the natural state of mankind. The novel’s unrelenting brutality and lyrical prose combine to create a vision of the West not as a place of human endeavour but as a hellish landscape where survival is dictated by the whims of violence.

In contrast to the fragile moralities of Hall’s Warlock, McCarthy offers no redemption, no moment of moral clarity. The characters of Blood Meridian move through a world devoid of hope, where violence reigns supreme and any attempt at imposing order is ultimately futile.

Sorcerer and Le Salaire de la Peur: Existential Desperation in the Jungle

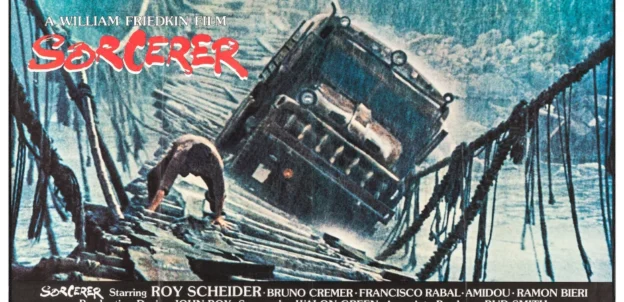

William Friedkin’s 1977 film Sorcerer, based on Georges Arnaud’s novel Le Salaire de la Peur, is a psychological thriller that explores the desperation and existential terror of a group of men tasked with transporting nitroglycerin across a treacherous jungle. The characters, each fleeing their pasts, are thrown into an environment that is hostile, indifferent, and as unpredictable as the dynamite they carry. The jungle, much like the desert in Blood Meridian, serves as a metaphor for a world where human lives are cheap, and survival is tenuous.

While Sorcerer deals with a more modern setting than Warlock or Blood Meridian, it shares with those works a sense of existential dread. The film’s protagonists, like the men of McCarthy’s West, are trapped in a world that offers no mercy. Their journey across the jungle becomes a crucible for testing the limits of human endurance and morality. Like the gunslingers and scalp hunters, the men of Sorcerer are driven by forces beyond their control, be they economic, historical, or elemental.

However, unlike McCarthy’s starkly nihilistic vision, Sorcerer allows for moments of camaraderie and brief flashes of humanity. The protagonists’ struggle against the elements and their circumstances serves to highlight their shared vulnerability, creating a tension between the desire for survival and the inevitability of death. In this way, Sorcerer offers a more nuanced portrayal of human resilience than the bleak determinism of Blood Meridian.

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me: Countercultural Rebellion and Existential Angst

Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me stands apart from the Western and survivalist themes of the other works but shares a common existential undercurrent. Set in the 1960s, the novel follows Gnossos Pappadopoulis, a college student navigating the chaos of the counterculture. While the setting is vastly different, the novel’s exploration of rebellion, freedom, and existential angst resonates with the themes of violence, lawlessness, and morality found in Warlock and Blood Meridian.

Gnossos, like Blaisedell or the Kid, is a figure in search of meaning in a world that seems bent on disorder. However, his rebellion is against societal norms and cultural stagnation, not the physical wilderness of the frontier or the jungle. The novel’s tone, tinged with satire and absurdity, offers a counterpoint to the grim seriousness of McCarthy and Hall, but the underlying themes of chaos and existential uncertainty remain. Fariña’s protagonist is as much a wanderer in search of purpose as the characters in Sorcerer, but his journey is internal, through the fragmented ideologies and shifting morals of 1960s America.

The Threads that Bind: Logic in Comparison

At first glance, comparing these works might seem unusual given their diverse settings and genres. However, there are deeper connections that weave these narratives together, offering a rich landscape for comparison. One of the most intriguing links is the relationship between Warlock by Oakley Hall and the countercultural work Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me by Richard Fariña. Fariña and Thomas Pynchon, both iconic figures of 1960s American literature, shared a personal connection through their university years at Cornell, where they formed a club dedicated to Warlock. This dedication to Oakley Hall’s novel indicates a shared intellectual fascination with themes of law, power, and moral ambiguity, elements central to both Warlock and Fariña’s own work.

This literary club, a reflection of Fariña’s and Pynchon’s admiration for Hall’s complex examination of Western mythology, hints at how these authors were drawn to narratives that challenged conventional morality and explored existential uncertainty. Fariña’s Been Down So Long might take place in a countercultural university setting, far removed from the violent frontiers of the American West, but the shared fascination with chaos, rebellion, and the question of authority links it to Warlock’s deeper philosophical concerns. This intellectual thread also underscores how the influence of Hall’s Warlock reached beyond the Western genre, impacting writers like Fariña and Pynchon, who were shaping postmodern literature.

Additionally, Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy can be seen as a natural progression of Hall’s deconstruction of the Western mythos. While Hall focuses on the fragility of law in the Old West, McCarthy takes this theme further, portraying violence not just as a breakdown of order but as a fundamental, inescapable force. The influence of Warlock on the Western genre may have paved the way for McCarthy to engage with these same ideas in a more extreme, nihilistic form. In this sense, Warlock functions as a keystone that binds these works together, with Hall’s exploration of law and power rippling through McCarthy’s grim frontier, Fariña’s countercultural rebellion, and even the existential desperation seen in Sorcerer.

Furthermore, Sorcerer shares the philosophical exploration of survival and morality seen in both Warlock and Blood Meridian. Though it trades the Western landscape for the dense jungles of South America, its themes of existential endurance and the indifferent forces of nature resonate deeply with McCarthy’s portrayal of a brutal, lawless frontier and Hall’s fragile attempts to impose order on chaos. The characters in Sorcerer are driven by desperation, much like the gunslingers of Warlock or the scalp hunters of Blood Meridian, and their struggle reflects a shared thread of existentialism, where survival itself becomes the only law.

The comparison also highlights how different historical periods and geographical settings, from the American West, to the jungles of Sorcerer, to the rebellious countercultural 1960s of Been Down So Long, all serve as backdrops for grappling with universal human concerns: the nature of power, the question of morality, and the struggle for meaning in a chaotic world.

Conclusion: Shared Themes of Chaos, Authority, and Survival

In conclusion, the logic of comparing these works arises from their shared thematic focus on existential uncertainty, violence, rebellion, and authority. Hall’s Warlock serves as a philosophical foundation that reverberates through these other works, whether in the grim determinism of McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, the existential dread of Sorcerer, or the countercultural rebellion of Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me. Each text reflects a unique approach to the timeless struggle between order and chaos, law and lawlessness, individual will and indifferent fate.

In Blood Meridian, McCarthy pushes Hall’s themes to an extreme, portraying violence not merely as an aberration but as an inevitable state of existence, casting doubt on any human attempts to create meaning or impose order. Here, Judge Holden becomes an avatar of unfathomable evil, challenging any notion of redemption or morality in the face of nature’s cruelty, pushing the ideas first explored in Warlock into an unflinchingly nihilistic vision of the American West.

Similarly, Sorcerer, with its jungle setting and fragile truce between survival and destruction, offers a modern echo of Warlock’s tension between law and chaos. The characters’ harrowing journey through the wilderness reflects a collective desperation, creating bonds of shared suffering even as the jungle and explosives embody the ever-present threat of annihilation. The story’s relentless challenges resonate with Blood Meridian’s perspective on the futility of imposing order on a hostile world, but unlike McCarthy, Sorcerer allows glimpses of humanity and resilience that speak to the possibility of camaraderie even amidst despair.

Finally, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me transposes Hall’s questions about law and order into a radically different setting: the turbulent, ideologically fraught world of 1960s counterculture. Fariña’s protagonist, Gnossos, rebels against societal norms in his own quest for purpose, paralleling the moral ambiguity and lawless freedom explored in Hall’s Warlock. The novel’s satirical edge and existential undertones offer a uniquely ironic take on the struggle for meaning, reflecting the influence of Hall’s work on postmodern literature through Fariña and Pynchon’s celebrated club dedicated to Warlock.

Together, these works invite readers to reflect on the persistence of existential and moral struggles across time, place, and genre. Each author, in their way, confronts the precariousness of human constructs, law, morality, authority, against the vast, indifferent forces of nature, violence, and existential doubt. By examining these works side by side, we can appreciate a shared legacy that questions the very fabric of human society, prompting readers to reconsider the nature of heroism, the role of authority, and the fragile boundary between civilization and chaos.