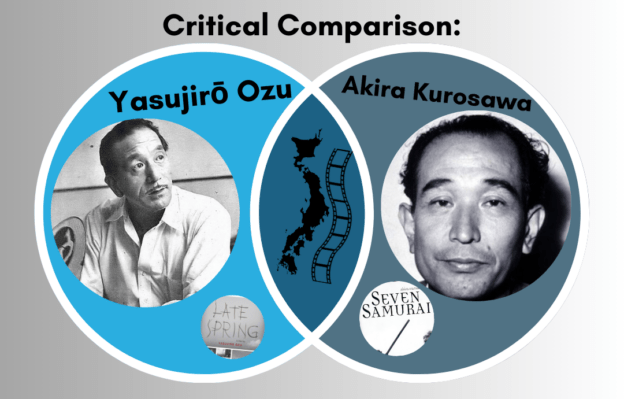

Yasujirō Ozu and Akira Kurosawa are two of the most celebrated filmmakers in Japanese cinema history, but their styles, themes, and approaches to cinema are notably different. Welcome to a comparison of their lives, works, and themes they explore.

Two giants in the realm of Japanese cinema, Yasujirō Ozu and Akira Kurosawa have left legacies that continue to influence filmmakers around the globe. Their works, although rooted in the same cultural milieu, differ dramatically in thematic depth, stylistic choices, and overall impact.

Lives:

- Ozu: Born in Tokyo in 1903, Ozu’s early life was marked by shifts between urban and rural settings, an experience that would later shape his deep understanding of family dynamics and societal transitions in Japan. He began his journey in cinema as an assistant cameraman, gradually finding his voice as a director. Although his career spanned both the silent era and World War II, Ozu’s personal life remained relatively private and unaffected by Japan’s turbulent history.

- Kurosawa: Born in 1910, also in Tokyo, Kurosawa hailed from a samurai family. The rich blend of Japanese tradition and Western culture in his upbringing became evident in his filmmaking. Unlike Ozu, Kurosawa’s personal struggles, particularly in his later years, including a suicide attempt, were more publicly known.

Works:

- Ozu: Renowned for films like “Late Spring,” “Tokyo Story,” and “An Autumn Afternoon,” Ozu’s works often exude quiet introspection. His stories revolve around domestic life, capturing the subtleties of familial relationships.

- Kurosawa: Kurosawa’s oeuvre boasts a broad spectrum, from the psychological depths of “Rashomon” to the epic grandeur of “Seven Samurai” and the Shakespearean gravitas of “Ran.” His films often tackle societal issues, moral dilemmas, and grand historical narratives.

Thematic Exploration:

- Ozu: Central to Ozu’s films are themes of generational conflict, the impermanence of life, and the everyday nuances of domestic life. The tension between modernity and tradition is palpable, painting a picture of a rapidly changing post-war Japan.

- Kurosawa: Morality stands out in Kurosawa’s films, whether exploring the subjective nature of truth in “Rashomon” or societal class divides in “High and Low.” War, conflict, and heroism, evident in epics like “Seven Samurai,” showcase a broader societal scope compared to Ozu’s intimate familial narratives.

Stylistic Differences:

- Ozu: Ozu’s style is marked by its stillness. He often used a camera placed at a low height (around the height of someone seated on a tatami mat) and employed static shots, allowing the story to unfold without unnecessary camera movement. His transitional pillow shots of landscapes, objects, or buildings are iconic, serving as reflective pauses.

- Kurosawa: Dynamic and varied, Kurosawa wasn’t afraid to employ movement, weather elements (like rain or wind), and dramatic compositions. His editing was dynamic, and he often used multiple cameras to capture scenes from different angles, a technique especially evident in his action sequences.

International vs. Local Influence:

- Ozu: While revered in Japan during his lifetime, Ozu’s international recognition came posthumously. His detailed, culturally-specific portrayal of Japanese life might have initially limited his global appeal. However, the universality of his themes, family, change, aging, has since been recognized and celebrated globally.

- Kurosawa: Kurosawa achieved international acclaim relatively early, with “Rashomon” winning at Venice in 1950. His synthesis of Western literary works and Japanese sensibilities made his films more accessible to global audiences. Many Hollywood films, like “The Magnificent Seven” (a remake of “Seven Samurai”) and “A Fistful of Dollars” (adapted from “Yojimbo”), attest to his widespread influence.

In conclusion, while both Ozu and Kurosawa navigated the waters of Japanese cinema, their ships sailed distinct paths. Ozu’s introspective, culturally-immersed tales contrast sharply with Kurosawa’s grand narratives and international appeal. Together, they offer a holistic glimpse into the versatility and depth of Japanese cinema.