This article examines the evolution of Western cinema through different “ages,” based on Alex Cox’s model of Traditional, Gritty, and Comedic Westerns, and explores whether additional phases, like the Neo-Western and Hybrid Western, might add depth to this framework. From the straightforward morality of early Westerns to the genre-blending explorations of the modern era, we trace the key films and themes that defined each age, examining how the Western has adapted to reflect changing societal values and cinematic tastes.

Introduction

Since its inception, the Western genre has evolved numerous times, mirroring changes in popular taste and cultural attitudes. Filmmaker Alex Cox, known for his work in cult and Western cinema, proposes a model that divides the genre into three primary “ages”: Traditional Westerns, Gritty Westerns, and Comedic Westerns. This model presents a valuable framework for understanding the genre’s trajectory, yet some argue that additional phases reflect even more nuance in the Western’s development.

In this article, we’ll explore Cox’s model and examine whether other key “ages” might add depth to our understanding of Western cinema. We’ll chronologically survey each era, identify notable films, and consider how changes in storytelling and adaptation shaped the genre, particularly concerning its literary roots.

This article was inspired by conversations with my son, Bill, during his time at the University of Birmingham, on his degree course in English Literature. This penultimate article is the twelfth of my “Myth of the West” cycle.

Table of Contents

The Traditional Western (1903–1950s)

Overview

Traditional Westerns, which dominated from the genre’s cinematic beginnings through the 1950s, cemented the moral and thematic foundations of the Western myth. These films feature clear distinctions between heroes and villains, with justice often achieved through decisive action by courageous figures, typically cowboys or lawmen. Here, the American frontier is portrayed as a battleground between civilisation and savagery, with characters embodying values of honour, sacrifice, and individualism.

Key Films

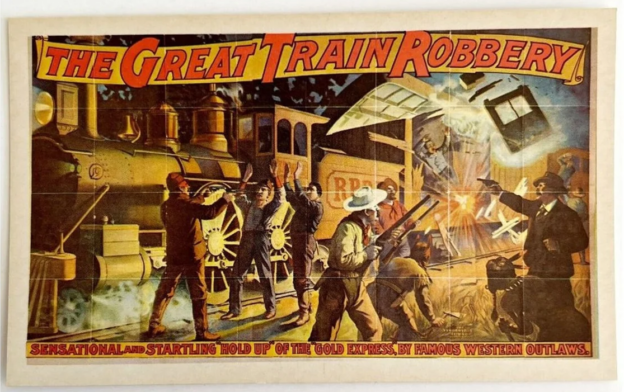

- The Great Train Robbery (1903) – Often considered the first Western film, establishing essential genre motifs.

- Stagecoach (1939) – Directed by John Ford, this film refined the Western archetype and introduced complex character dynamics.

- High Noon (1952) – Though edging towards ambiguity, High Noon adheres to the classic Western’s moral code, with its hero standing alone for justice.

Source Material

This age drew heavily from pulp fiction, dime novels, and works by authors like Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour, which idealised the West and helped create clear-cut depictions of good versus evil. These sources provided straightforward narratives that were easily adapted to film’s visual storytelling.

The Revisionist or Gritty Western (1960s–1980s)

Overview

Alex Cox’s concept of the “Gritty Western” begins with films like Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964), marking a significant shift from the genre’s earlier ideals. Revisionist Westerns deconstruct the traditional, clear-cut morality of the genre, focusing instead on morally ambiguous protagonists, stark violence, and the darker side of the frontier. Reflecting the political and social upheavals of the 1960s and 70s, these films question the classic “hero” and often explore themes of greed, corruption, and existential struggle. In contrast to the optimism of earlier Westerns, the gritty films reveal a West marked by betrayal, lawlessness, and the toll of survival.

Key Films

- A Fistful of Dollars (1964) – Directed by Sergio Leone, this film inaugurated the Spaghetti Western genre and introduced the morally complex “Man with No Name.”

- The Wild Bunch (1969) – Known for its graphic violence and anti-heroic characters, Sam Peckinpah’s film pushed the boundaries of the genre.

- High Plains Drifter (1973) – Clint Eastwood’s unsettling portrayal of vengeance and moral decay set in a desolate Western town.

- Unforgiven (1992) – While arriving at the tail end of the Revisionist period, Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven epitomises the gritty, morally complex tone of the Revisionist Western.

Source Material

The Gritty Westerns often drew inspiration from existential themes, literature by authors like Elmore Leonard, and the works of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah. These filmmakers took cues from hardboiled fiction and pulp novels that presented the West with a cynical lens, exploring themes of isolation and the moral gray areas that blur hero and villain.

The Comedic Western (1970s–1980s)

Overview

The third age in Cox’s model, the Comedic Western, emerged as audiences began to tire of the genre’s bleakness and moral ambiguity. These films used humour and parody to reinvigorate the Western, often subverting or poking fun at its classic tropes. While some of these films still involve elements of action and heroism, they often mock the exaggerated machismo and clichés established in previous Westerns.

Key Films

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) – A blend of comedy and adventure, this film uses wit and irony to explore the lives of outlaws.

- Blazing Saddles (1974) – Mel Brooks’ satirical take on the Western genre, addressing issues of racism and breaking genre conventions.

- My Name is Nobody (1973) – Starring Terence Hill, this Italian Western uses comedic elements to critique the archetypal gunslinger.

Source Material

While many comedic Westerns were not directly based on books, they drew from established Western tropes that were often explored in pulp fiction and earlier films. The humorous approach allowed filmmakers to experiment with the genre, playing with the exaggerated elements of cowboy legends that pulp fiction popularised.

The Neo-Western (1990s–Present)

Overview

Emerging as an extension of the Revisionist Western, the Neo-Western genre brings Western themes into modern or contemporary settings, often emphasising moral ambiguity, rugged landscapes, and individualism within present-day contexts. Neo-Westerns examine the persistence of frontier values in the modern world, focusing on themes of justice, lawlessness, and survival in the face of systemic breakdown.

Key Films

- No Country for Old Men (2007) – A modern-day Western that explores violence, fate, and existential dread in the desolate Texas landscape.

- Hell or High Water (2016) – A contemporary take on the outlaw story, focusing on family loyalty and the struggles of small-town America.

- Logan (2017) – Though technically a superhero film, Logan uses the Western framework to explore themes of redemption, ageing, and sacrifice.

Source Material

Neo-Westerns are often inspired by modern literature, including works by Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry, which explore the residual impact of the frontier ethos in modern society. These stories typically portray characters facing moral and existential crises, with Western motifs providing a framework for complex themes.

Genres and Subgenres: Beyond “Ages” to Themes and Styles

While Alex Cox’s model categorizes Westerns into “ages,” the genre’s flexibility also lends itself to various subgenres that blend Western motifs with different narrative styles, aesthetics, and genres. These subgenres expand the scope of the Western and show its adaptability across diverse storytelling approaches and cultural perspectives.

Key Subgenres

- Acid Western

- Acid Westerns offer surreal and often psychedelic interpretations of the genre, questioning traditional narratives of heroism and exploring countercultural themes. These films, like El Topo (1970) and Dead Man (1995), are abstract and philosophical, often portraying the West as a place of existential and moral ambiguity.

- Horror Western

- Combining supernatural and horror elements with Western settings, these films infuse classic frontier tales with themes of terror, isolation, and the supernatural. Examples include Bone Tomahawk (2015) and Ravenous (1999), which use horror to intensify the hostility and loneliness of the Western landscape.

- Sci-Fi Western

- By merging Western and science fiction genres, Sci-Fi Westerns like Westworld (1973, 2016 series) and Cowboys & Aliens (2011) explore futuristic settings while retaining Western motifs like lawlessness and frontier justice. The fusion of these elements creates fresh landscapes where traditional Western themes intersect with advanced technology and alien encounters.

- International Westerns

- Westerns have been adapted and reimagined by different cultures, producing unique “Western” experiences beyond the American frontier. Japanese films like Yojimbo (1961) reflect the Western’s influence on samurai narratives, while Australian Outback Westerns like The Proposition (2005) tackle similar themes of survival and lawlessness in distinct settings. The South Korean film The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008) is another example, adapting Western tropes to East Asian landscapes.

- Contemporary or Neo-Western

- Neo-Westerns bring the genre into the present day, exploring themes of justice, individualism, and lawlessness in modern settings. Films like No Country for Old Men (2007) and Hell or High Water (2016) portray a contemporary world where the ethos of the West persists, examining the impact of these values in a changing society.

- Fantasy Western

- Fantasy Westerns introduce mythical or supernatural elements into the genre, creating worlds where legends come alive. Examples include Jonah Hex (2010) and the Dark Tower series, which blend Western themes with fantasy elements, like magic or alternate realities, expanding the frontier beyond the earthly realm.

- Romantic Western

- Romantic Westerns centre on love stories within the rugged and often unforgiving environment of the frontier. These films explore themes of loyalty, resilience, and the complex dynamics between characters in the wild, untamed West. Romantic Westerns often depict the sacrifices and challenges lovers face, set against a landscape that tests their bonds. Notable examples include Cimarron (1931) and McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), where love and companionship are interwoven with themes of survival, morality, and independence.

- Political Western

- Political Westerns tackle the societal and political tensions of the time, examining the ethics and power struggles within frontier communities. Often used as a lens to scrutinize broader American values, these Westerns question justice, authority, and collective morality. The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), a prime example, delves into mob justice and the consequences of groupthink, while Lonely Are the Brave (1962) critiques the rigid systems that stifle individual freedom. This subgenre reveals the Western frontier as a microcosm of America’s own ideological battles.

- Musical Western

- Musical Westerns blend the genre’s traditional elements with the vibrancy of song and dance, offering a lighter and more whimsical portrayal of frontier life. In films like Paint Your Wagon (1969) and Oklahoma! (1955), the landscape of the West serves as a backdrop for romantic entanglements, community celebrations, and comedic escapades, accompanied by memorable musical numbers. These films often celebrate the camaraderie and idealism of Western life while poking fun at its myths and legends.

- LGBTQ+ Western

- LGBTQ+ Westerns bring queer narratives and characters to the traditionally hypermasculine world of the frontier, challenging the genre’s conventions and expanding its emotional and thematic range. These films highlight themes of love, identity, and social isolation, set against the backdrop of the American West. Brokeback Mountain (2005) broke new ground with its portrayal of forbidden love between two cowboys, capturing the tension between personal freedom and societal expectations. The Power of the Dog (2021) further explores repressed sexuality and power dynamics within a Western setting, adding psychological depth to the genre’s exploration of masculinity and identity. LGBTQ+ Westerns offer fresh perspectives, reflecting the genre’s ability to evolve and represent diverse experiences in complex, nuanced ways.

Conclusion: Validity of Cox’s Model and Beyond

Alex Cox’s model offers a useful lens for understanding the evolution of the Western genre, focusing on the shifts from traditional moral frameworks to gritty realism and, eventually, self-parody.

By viewing the Western not just in terms of “ages” but also through subgenres, we gain a fuller understanding of the genre’s rich adaptability and thematic depth. The Western’s enduring appeal lies in its capacity to reflect evolving values, fears, and ambitions, proving that even as the frontier shifts and changes, the mythos of the West continues to resonate across cultures and genres.

Examining these ages and the literature that inspired them reveals how the West has both responded to and shaped American identity, reflecting the timeless conflict between law and chaos, civilisation and wilderness, and individualism and community.