Cybersecurity feels foundational today, but as a discipline, it is startlingly young. This article argues that cyber is still in its infancy, especially when compared to IT or financial governance, and outlines why this newness matters. From AI security and quantum disruption to the structural challenges facing certification, education, and regulation, the piece maps both future directions and the underlying trends shaping the field. In a world where cyber is everywhere, this article insists: we’re just getting started.

Contents

- Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Context: Cyber Compared to Human and Technological History

- Cyber Compared to the History of IT

- The Speed of Change: Cyber’s Compressed Evolution

- Future Directions: The Next Wave of Cyber

- 1. AI Security, Ethics, and Weaponisation

- 2. Quantum Computing, Cryptography, and the Post-Quantum Era

- 3. Cyber Psychology and Behavioural Risk

- 4. Cyber Resilience and Automated Response

- 5. Universal Risk Quantification and Supply Chain TPRM

- 6. Tools Consolidation and Platformisation

- 7. Revisiting Physicality: Infrastructure for the Secure Future

- 8. Security Ubiquity: Trust by Default

- Structural Forces Shaping the Field: Emerging Trends

- A. Regulatory Expansion and Enforcement

- B. AI Agents as Attack Tools

- C. Professionalisation and Role Clarity

- D. Demographic Skew in Penetration Testing

- E. Graduate Pipeline Mismatch

- F. Shift from Cybersecurity to Cyber Resilience

- G. Erosion of Trust in Traditional Certifications

- H. Tool Fatigue and Integration Pressure

- I. Attack Democratisation: Cybercrime-as-a-Service

- J. Ethical Grey Zones and Surveillance Backlash

- K. Geopolitical and National Cyber Posturing

- L. Enterprise vs. Rural and SME Cyber Divide

- M. Data Sovereignty and Cloud Decentralisation

- What This Means for Innovation

- Conclusion: Still in Its Infancy

Introduction

Cybersecurity today feels foundational, baked into regulation, boardroom agendas, military strategy, and national infrastructure. Yet the term cyber, the discipline of cybersecurity, and the institutions supporting it are startlingly recent. Compared to the long history of human technology, or even the short but intense development of computing, cyber is barely out of the cradle.

This article sets out a simple but essential proposition: we are only at the very beginning of what cyber will become.

Historical Context: Cyber Compared to Human and Technological History

Let’s start with the scale of comparison.

- Writing systems emerged around 3200 BCE

- Double-entry bookkeeping dates to the 13th century

- Insurance risk models were formalised in the 17th century

- Modern computing took off in the 1940s–50s

- Cybersecurity, as a distinct concept, appeared in force post-1990s

- The UK’s first Cyber Security Strategy? Just 2009

In historical terms, cyber is younger than the iPhone. Younger than Google. Younger than Amazon.

In a series of historical retrospectives:

- The Rise of the CISO

- A Brief History of Penetration Testing

- A History of the Terms: Risk Assessment, Risk Management, and GRC

- A Brief History of the Term Cyber (meaning Cybersecurity)

We see a recurring pattern: the core terminology, roles, and frameworks of cybersecurity all solidified only in the past 25 to 30 years. Even the field of Cyber Risk Quantification, explored in:

Is still in its experimental phase, without a universally accepted model.

The language, roles, standards, certifications, and norms of cybersecurity are all less than 30 years old, and in many domains, especially in SMEs, education, or developing regions, are still poorly understood or inconsistently applied.

Cyber Compared to the History of IT

Even when compared to information technology itself, cyber is a latecomer.

- IT roles like systems administrator or database manager have existed since the 1960s–70s

- Programming languages like COBOL, Fortran, and C all predate any formal use of “cyber”

- The first antivirus software didn’t appear until the late 1980s

- The term “cybersecurity” wasn’t widespread until post-2000

While IT developed incrementally, cyber emerged reactively, as a response to risk, breaches, and threat actors. It was not embedded from the start, and we’re still correcting for that omission.

Today’s patchwork of tools, frameworks, and job titles reflects this origin: cyber evolved as a defensive scramble, not as a coherent discipline.

The Speed of Change: Cyber’s Compressed Evolution

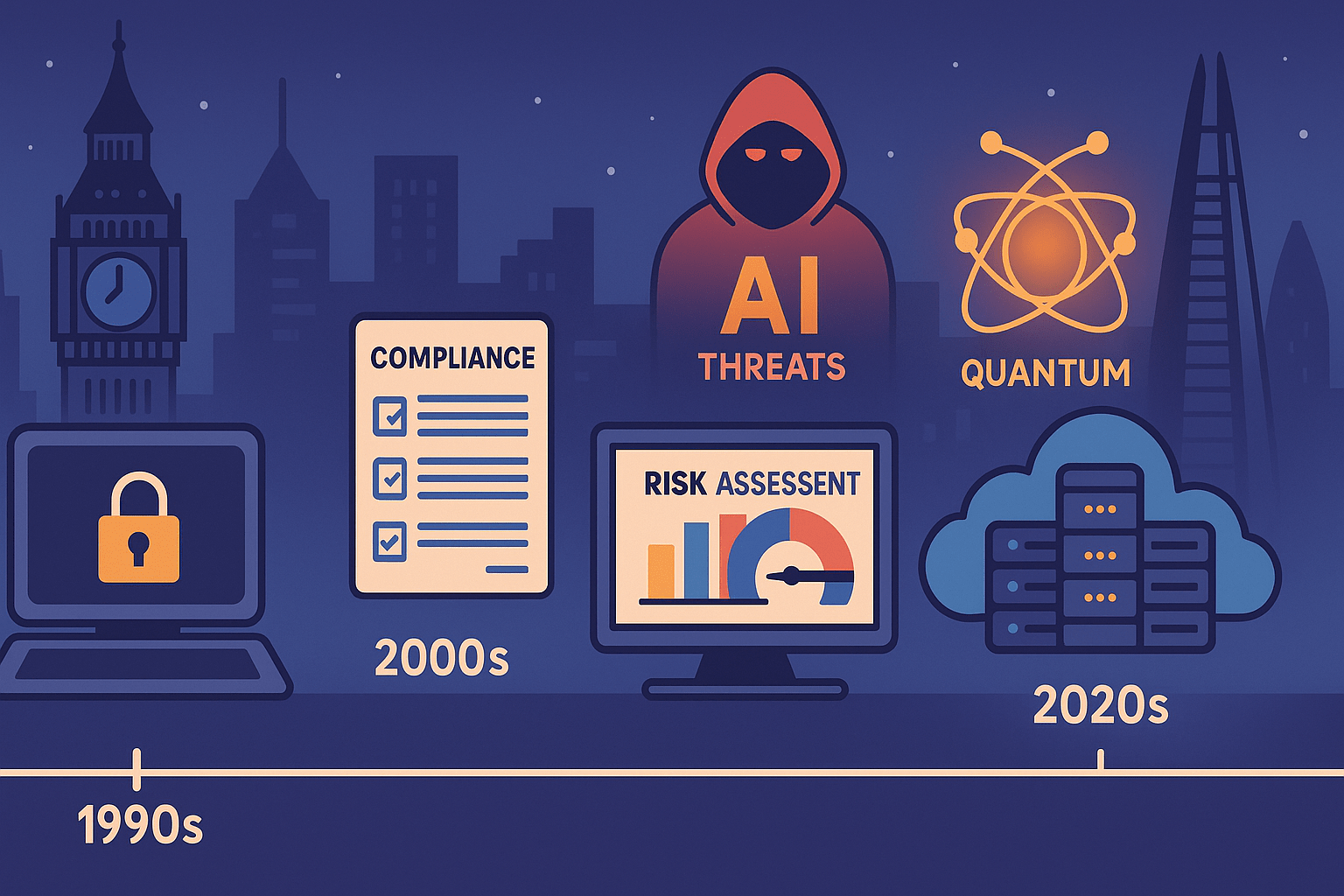

Despite its youth, cyber has undergone rapid and uneven evolution:

- In the 1990s, firewalls and antivirus software were enough.

- In the 2000s, compliance (e.g. SOX, PCI DSS) shaped priorities.

- In the 2010s, data breaches and ransomware made cyber mainstream.

- Now, in the 2020s, cyber is merging with AI, national security, geopolitics, and privacy.

This is not a normal pace of professional maturation. Most fields develop over centuries. Cyber is compressing its institutionalisation, professionalisation, and globalisation into a few short decades.

That makes it unstable, exciting, and wide open for innovation.

Future Directions: The Next Wave of Cyber

Cyber is no longer just a matter of firewalls and phishing, its frontier is expanding into adjacent scientific, behavioural, and strategic domains.

Just as early medicine evolved from bloodletting to biochemistry, cyber is moving from vague policies and patching toward science, structure, and strategy.

The next decade will see deep transformations driven by:

1. AI Security, Ethics, and Weaponisation

As AI capabilities advance, so do threats. From deepfake social engineering to autonomous attack agents, cybersecurity must confront not just how to defend against AI, but how to secure AI itself. This includes:

- AI model integrity and poisoning

- Generative adversarial attacks

- Ethical and policy frameworks for dual-use AI technologies

- Regulatory responses to autonomous decision-making in critical systems

AI is both a force multiplier and a threat vector, and cyber must evolve to govern its use and misuse.

2. Quantum Computing, Cryptography, and the Post-Quantum Era

Quantum computing presents both promise and peril. While still emerging, its potential to break today’s encryption poses an existential threat to long-term data confidentiality. Preparations are already underway:

- Development of post-quantum cryptographic standards (NIST PQC finalists, UK NCSC guidance)

- Long-term risk planning for sectors with data-retention obligations (e.g. legal, defence, health)

- Hybrid cryptographic schemes to bridge legacy systems into a quantum-secure future

Quantum will redefine what “secure” means in the coming decades.

3. Cyber Psychology and Behavioural Risk

The human element remains the weakest link in security, but also the least understood. Emerging research in cyber psychology seeks to map:

- Human error, deception, and susceptibility

- Fatigue, burnout, and decision-making under stress

- Cultural and cognitive factors in insider risk

- Behavioural indicators of compromise and exfiltration

This field is moving beyond “awareness training” to behavioural modelling, sentiment analysis, and predictive profiling, essential in understanding both attackers and users.

4. Cyber Resilience and Automated Response

Security is no longer just about prevention; it’s about enduring and recovering. Cyber resilience focuses on:

- Automated containment and failover systems

- Business continuity and recovery-by-design

- Real-time incident orchestration across distributed systems

- Stress-testing organisational and societal cyber capacity

The shift is from “Can we stop it?” to “Can we survive it?”

5. Universal Risk Quantification and Supply Chain TPRM

The need to measure cyber risk like financial risk is intensifying. Organisations are seeking:

- Standardised risk scoring (akin to credit scores)

- Continuous Third-Party Risk Management (TPRM) across sprawling supply chains

- Integration of cyber risk into enterprise portfolio management

- Risk pricing for insurance, procurement, and investment

This will reshape how cyber is reported, budgeted, and governed.

6. Tools Consolidation and Platformisation

The fragmented landscape of cybersecurity tooling, SIEMs, GRC systems, vulnerability scanners, DLP, threat intelligence feeds, is giving way to:

- Consolidated platforms with integrated functionality

- API-driven ecosystems and middleware

- Real-time dashboards combining compliance, threat, and risk intelligence

- Reduced cognitive load and operational friction for security teams

The future lies in coherence, not complexity.

7. Revisiting Physicality: Infrastructure for the Secure Future

As we increasingly rely on cloud platforms, AI, and IoT, the physical infrastructure that powers cyber becomes critical. New security frontiers include:

- Secure data centre design and sovereign hosting locations

- Hardened network architecture and quantum-resistant fibre routing

- Physical-layer attacks on satellites, undersea cables, and industrial control systems

- Edge computing infrastructure requires decentralised but secure oversight

Cybersecurity must once again confront its physical roots in power, space, latency, and access.

8. Security Ubiquity: Trust by Default

In the future, security won’t be a bolt-on or a specialist’s responsibility—it will be everywhere and assumed. We’re moving toward:

- Zero-trust architectures are built into operating systems and APIs

- Secure-by-design frameworks are becoming regulatory expectations

- Continuous verification: real-time attestation, behavioural baselining, identity assurance

- Cross-functional responsibility: security baked into DevOps, HR, legal, product, and beyond

Security will become as ubiquitous and invisible as electricity. Trust will be ambient, not optional.

Structural Forces Shaping the Field: Emerging Trends

These trends are not just technological; they are institutional, social, and demographic. They will shape the cyber industry as profoundly as any new attack vector or tool.

A. Regulatory Expansion and Enforcement

- Proliferation of region-specific laws (e.g. DORA, NIS2, DPDI, SEC cyber rules)

- Stricter penalties, mandatory reporting, and third-party liability

- Compliance as continuous, real-time, and measurable

B. AI Agents as Attack Tools

- LLMs and agentic AI used for phishing, social engineering, automation of reconnaissance

- AI as “cyber intern” for attackers, redefining speed and scale

- Dual-use concerns around open-source LLMs and exploit chains

C. Professionalisation and Role Clarity

- The UK Cyber Security Council (UK CSC) and CIISec chartership initiatives

- Push to define and certify roles in offensive security, cyber governance, and resilience

- Fragmentation between policy and practice, slow adoption despite demand

D. Demographic Skew in Penetration Testing

- Ageing cohort of senior pen testers

- High entry barriers: 7+ years of technical experience or elite certifications

- Lack of pathways for mentoring or structured career transition

E. Graduate Pipeline Mismatch

- Hundreds of UK universities are offering cyber degrees, but:

- Low practical readiness

- Limited exposure to real-world tooling or incidents

- Employers’ reluctance to hire junior staff who require training

- Result: underemployment and burnout among early-career professionals

F. Shift from Cybersecurity to Cyber Resilience

- Boards increasingly accept that breaches are inevitable

- Focus on MTTD/MTTR (Mean Time to Detect/Respond), not just prevention

- Insurance, business continuity, and stakeholder communication are rising in priority

G. Erosion of Trust in Traditional Certifications

- Growing scepticism of CEH, CISSP, and even OSCP as reliable indicators

- Movement toward skills demonstration (labs, red team exercises, CTFs)

- Rise of vendor-driven certs (e.g., AWS, Microsoft, Splunk) valued over generalist ones

H. Tool Fatigue and Integration Pressure

- Enterprises are drowning in dashboards, alerts, and tools that don’t speak to each other

- Shift to platforms, consolidation, and “single pane of glass” strategies

I. Attack Democratisation: Cybercrime-as-a-Service

- Phishing kits, ransomware affiliates, and exploit marketplaces

- Anyone can “buy” access or tooling, threat actors no longer need deep skills

- Industrialisation of cybercrime reduces barriers to entry

J. Ethical Grey Zones and Surveillance Backlash

- Tensions between security and civil liberties (e.g. spyware, facial recognition)

- Public pushback against pervasive surveillance and data scraping

- Emerging need for Cyber Ethics Officers and ethics-aware policies

K. Geopolitical and National Cyber Posturing

- State-aligned actors (APT groups) are increasingly part of global conflicts

- Cyber becomes an extension of diplomacy, deterrence, and espionage

- Organisations caught in crossfire (e.g. sanctions, supply chain scrutiny)

L. Enterprise vs. Rural and SME Cyber Divide

- Large enterprises are improving posture, but SMEs and rural orgs lag dramatically

- Lack of funding, awareness, or staff

- Creates weak links in regional and national supply chains

M. Data Sovereignty and Cloud Decentralisation

- Concern over who controls and audits cloud infrastructure

- Legal conflicts between local regulations and global providers

- Push toward “sovereign clouds”, edge computing, and hybrid models

What This Means for Innovation

The newness of cyber brings three important implications:

- No One Has It All Figured Out

There is no universal playbook. Best practices vary wildly by sector, geography, and size. This gives innovators room to experiment and disrupt, from startups to standards bodies. - Tooling Is Immature

Many cyber tools, GRC platforms, SIEM systems, risk scoring models, are still clunky, expensive, and built on outdated assumptions. There is enormous scope for rethinking usability, scalability, and integration. - The Workforce Is Emerging

Job titles, career paths, and qualifications are still in flux. Compare “CISO” to “CFO”: one is 150 years old, the other barely 25. This makes cyber fertile ground for new roles, diversity, and rethinking leadership.

Conclusion: Still in Its Infancy

Cyber may be omnipresent in conversation, but as a discipline, it is still nascent. Its tools, language, institutions, and cultural understanding are barely a generation old.

That’s not a weakness, it’s a signal of opportunity.

In the next decade, cyber will likely diverge, professionalise, and converge all at once. We’ll see new subfields, new academic disciplines, new careers, and new kinds of risk, ones we can’t yet name.

The most important thing to understand about cyber today?

It’s new. Which means it’s not done yet.