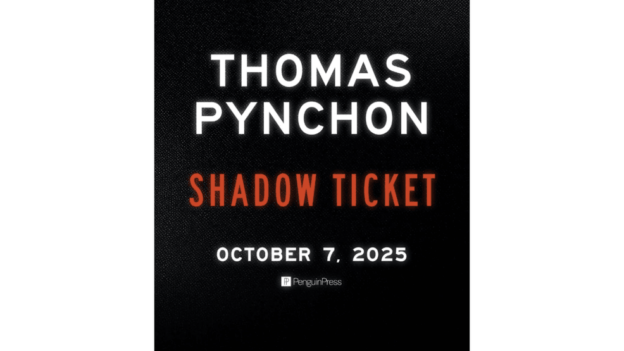

What’s that you say? Thomas Pynchon announces a new book to be released in October 2025? No frigging way, Dude. Will it be multi-episodic, akin to Gravity’s Rainbow? Mason and Dixon, Against the Day? V even? Or more accessible, Inherent Vice, Vineland, or Bleeding Edge? Am I buying a copy? Of course I am.

When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, I was working as a foreign money forgery expert at Lloyds International Operations Centre (opposite Birmingham Town Hall, now a Regus drop-in office building). Days were full of precision and protocol, but nights were for paranoia, Burroughs, Lovecraft, Ballard, and most of all, Pynchon. That novel didn’t just crack open the modern world, it unravelled it, rewired my understanding of systems, conspiracy, entropy, and the absurdity of control. It felt like a secret text for those who lived between borders: financial, psychological, and national.

At 87, Thomas Pynchon announced Shadow Ticket, his first novel in over a decade. Set in the Big Band era and wrapped in noir, it follows a detective chasing a cheese heiress across a crumbling world of spies, Nazis, swing musicians and paranormal outlaws. It sounds gloriously mad and somehow perfect for now.

For me, this isn’t just literary news. It’s like hearing from a long-lost godfather of thought. Pynchon shaped how I approached systems, risk, and even cybersecurity. His obsession with hidden structures mirrors the logic of encryption and forgery. The gaps in meaning, the signals in noise, these were the kinds of patterns I once looked for in counterfeit Deutschmark notes and now look for in vulnerabilities and attack vectors.

And there’s something elegant about this return being a detective story. Beneath all his intellectual chaos, Pynchon has always written about people trying to solve unresolvable mysteries. Hicks McTaggart, the hero of Shadow Ticket, sounds like the latest in a long line of lonely searchers, trying to dance his way back to a world that might no longer exist.

It reminds me of the surreal clarity I felt decoding financial crime, one note at a time, by day and reading about Slothrop’s scattered identity by night. Both pursuits, in their way, were about following the threads that the world prefers you not to see.

I’ll be there in October, waiting to meet Hicks and to see what Pynchon has smuggled into the text this time. After all, if there’s one thing I’ve learned from both my career and my reading, it’s that the real story is always what’s hidden behind the official narrative, and nobody hides it better than Pynchon.