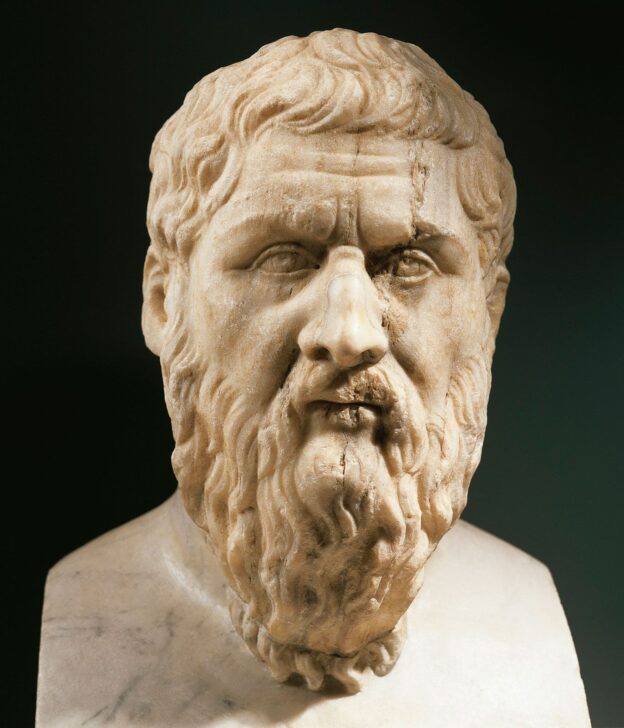

Plato famously (and controversially) argued that all democracies inevitably collapse into tyranny. For a modern reader, raised on ideals of popular sovereignty, civil rights, and universal suffrage, this sounds alarmist or even offensive. But to dismiss Plato’s warning outright would be to miss a deeper meditation on the fragility of political systems and human nature itself.

This short article was inspired by a conversation with a couple of friends about two weeks ago at a Birthday party in the Jewlery Quarter (of Birmingham), discussing, of course, the current state of the world, vis-a-vis the rise of demogogory from Putin, to Erdogan, to Zelenskyy, and of course, Trump.

One friend described the European Union as a kind of marriage of localised democracies, tied together by bureaucracy, a structure not dissimilar to the United States, where state-level democracies are connected through a wider federal system. Both models try to balance local autonomy with shared governance, but each faces the same tension: how to maintain democratic legitimacy across multiple layers of authority. In the EU, this often looks like democratic states feeding into an unelected but technocratic centre, a tension that fuelled Brexit, where frustration with perceived democratic distance helped tip the vote. In the US, the federal system is under constant strain from deep political polarisation, legal clashes between states and the Supreme Court, and fundamental disagreements over who should decide on key issues like abortion rights, gun laws, and voting access. Both systems reveal the challenge of scale, how to keep democracy meaningful, accountable, and human when layered governance starts to feel distant or imposed.

Getting back to the crux of the article I’ll cover what Plato had to say, what his examples were, the ups and downs of democracy, and his thoughts on the cyclic nature of the rise and fall and rise again of democracy.

Why Did Plato Say That? What Were His Examples?

Plato’s critique of democracy is most clearly laid out in The Republic, particularly in Book VIII. There, he describes a cycle of regimes: aristocracy (rule by the best), timocracy (rule by the honour-loving), oligarchy (rule by the wealthy), democracy (rule by the many), and tyranny (rule by one).

In Plato’s view, democracy emerges when the masses, tired of oligarchic inequality, revolt and install a system of equality and freedom. But therein lies the problem. In a society that prizes freedom above all else, discipline erodes, authority becomes suspect, and individuals come to do as they please. The state, in Plato’s metaphor, becomes like a ship where the crew mutinies and the passengers pick the captain based on charm rather than skill.

In such chaos, Plato believed, a charismatic leader inevitably arises, a demagogue who claims to represent the people, but who consolidates power, eliminates rivals, and becomes a tyrant. His real-world example was the collapse of Athenian democracy into tyranny during his own lifetime, especially the rule of the Thirty Tyrants after the Peloponnesian War.

The Good and Bad of Democracy

Democracy remains the most widely endorsed form of government in the modern world for good reason. It is the single largest expression of the popular will and, ideally, ensures that power is distributed, accountability is maintained, and change can happen peacefully.

Advantages of Democracy

- Representation: Citizens have a say in who governs them.

- Checks and balances: Institutions prevent overreach.

- Freedom of expression: Democracies protect dissent and minority views.

- Peaceful transitions: Power changes hands without violence.

- Rule of law: Ideally, laws apply to all, regardless of rank.

My personal favourite example is from the Battle of Marathon where the newly minted Democray of Athens proved that personal investment was highest in a system where everyone was counted equally, and that they could overcome against great odds.

Disadvantages of Democracy

- Populism and demagoguery: Skilled manipulators can sway the masses.

- Short-termism: Politicians often focus on elections rather than long-term good.

- Polarisation: The very openness of debate can harden divisions.

- Inefficiency: Decision-making can be slow and bogged down in bureaucracy.

- Voter disengagement: When citizens feel unheard or overwhelmed, participation wanes.

A recent example is Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey. Initially elected in a democratic system, Erdoğan systematically eroded institutional independence, jailed opponents and journalists, and shifted the country toward authoritarian presidential rule, all while maintaining a veneer of electoral legitimacy. Cemented now by his heavy-handed treatment of Ekrem İmamoğlu, the Mayor of Istanbul.

From Justice to Fragility: A Democracy’s Lifecycle?

Many democracies are indeed born from struggle, against monarchy, colonialism, dictatorship, or injustice. The founding story is often one of moral clarity, collective resolve, and a thirst for justice. But as generations pass, that founding memory fades. Institutions built to guard against oppression begin to sag under the weight of complacency, corruption, and disillusionment.

At this point, Plato’s warning re-emerges. If the public loses faith in their representatives, and the process of change seems futile or rigged, a space opens for the demagogue. This figure doesn’t just offer policies, they offer emotional clarity, a scapegoat, and a promise to “restore greatness.”

Democracy, paradoxically, can enable such figures by giving them a platform. And once in power, they can erode the very structures that put them there. Thus, democracy becomes its own undoing, not because it is inherently bad, but because it lacks defences against its most dangerous internal enemy: unchecked populism.

Conclusion and Some Thoughts

Plato’s claim that all democracies end in dictatorships is not a prophecy but a provocation. It invites us to look closely at our own systems, to examine the health of our institutions, and to remember that democracy is not self-sustaining. It must be protected, renewed, and improved constantly. Otherwise, its greatest virtue, freedom, may become its fatal flaw.

My view is that democracy is the best we have, and we should defend it stringently, even stubbornly. Plato might disagree. His answer to democracy’s flaws was the rule of philosopher-kings, wise, just, and incorruptible. But I find that vision even more idealistic, and ultimately more vulnerable, than the democratic dream it replaces, more akin to the flights of fancy we see in socialism and communism. It rests on the same flawed hope that people, or at least some elite group of them, will be consistently generous, fair, and selfless. That assumption erodes both socialism and communism, and I suspect it would collapse Plato’s Republic too.

The Battle of Marathon teaches us that when people are invested together, equally and fairly, they can overcome great odds and keep doing so, long after fear or tyranny tries to wear them down. Marathon was a watershed moment in the Greco-Persian wars. It showed the Greeks that the Persians could be beaten. It proved that a citizen army, drawn from a democratic polis like Athens, could triumph against a vast empire. It also demonstrated that the Athenians, without Spartan help, could defend their land and ideals. That victory sparked a flourishing of Classical Greek civilisation that continues to shape Western thought today.

This, in turn, raises a deeper question: is the failure of democracies intrinsic to their nature, as Plato believed, or is it simply a matter of scale? Can systems built on participation and fairness hold their shape as they grow ever larger and more complex? Or are these two challenges, internal decay and expansive reach, different sides of the same problem? As we watch modern democracies strain under the weight of bureaucracy, inequality, and polarisation, it’s worth asking whether what weakens them is a fatal flaw, or merely a failure to adapt.

So while democracy may be fragile, it is also powerful. It is capable of greatness when citizens take responsibility, participate with care, and stand together against those who would erode it from within.