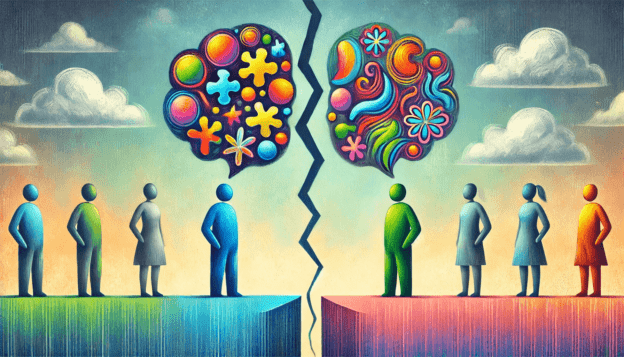

Milton’s Double Empathy Theory, developed by Damian Milton in 2012, challenges the traditional “empathy deficit” model of autism. Rather than seeing autistic individuals as lacking empathy, it argues that communication difficulties between autistic and non-autistic people arise from a reciprocal empathy gap, where both groups struggle to understand each other’s perspectives due to differences in communication and social experience.

Increasing evidence supports the theory, including research in areas like social cognition, interaction studies, and neurodiversity. Here’s a summary of the key evidence.

Contents

1. Empathy is not reduced but different

Milton argued that autistic individuals do not inherently lack empathy; instead, they may experience heightened emotional empathy but struggle with cognitive empathy (understanding others’ perspectives). Several studies confirm this distinction:

- Smith (2009) found that autistic individuals showed typical emotional responses but had challenges interpreting social cues.

- Song et al. (2019) demonstrated that autistic individuals were just as capable of empathy toward other autistic people, supporting the idea of shared understanding within neurodivergent groups.

2. Mismatch in communication styles

Research into social interaction shows a mismatch in communication between autistic and non-autistic people, rather than a one-sided deficit:

- Crompton et al. (2020) found that autistic individuals communicate more effectively and naturally with other autistic people than with non-autistic individuals. This supports the Double Empathy Theory, as it highlights how communication challenges are mutual rather than solely the responsibility of the autistic person.

- Heasman & Gillespie (2018) focused on perspective-taking and found that misunderstandings arise due to different social expectations and assumptions between neurotypical and autistic people.

3. Autistic-to-Autistic Interaction

The theory is further supported by studies showing that autistic people often find interacting with one another easier and less stressful:

- Crompton et al. (2020) coined the phrase “The Autistic Advantage”, where autistic individuals have better rapport and understanding with each other compared to mixed neurotype groups. This undermines the assumption that autistic people universally struggle with social interaction.

4. Social Reciprocity Studies

Double Empathy Theory also aligns with studies on reciprocity and shared social experiences:

- Morrison et al. (2020) found that neurotypical participants also had difficulty interpreting autistic people’s social cues and intentions, suggesting the problem is two-way.

- Edey et al. (2016) demonstrated that neurotypical individuals were just as likely to misinterpret the mental states of autistic people as the reverse.

5. Self-Reported Empathy and Social Experience

Qualitative research also offers strong evidence. Many autistic individuals describe feeling deep emotional empathy but struggling to express it in conventional ways:

- Milton (2012) highlighted personal accounts from autistic individuals who expressed frustration at being perceived as unemotional or unempathetic simply because their communication did not conform to neurotypical norms.

Conclusion

The evidence for the Double Empathy Theory continues to grow, highlighting that communication breakdowns between autistic and non-autistic individuals are bidirectional. This perspective has important implications for how we approach autism research, social interaction, and inclusion, focusing less on fixing autistic “deficits” and more on fostering mutual understanding across neurotypes.

References

- Dr Damian Milton (2017), A mismatch of salience. Pavilion

- Milton, D. (2012) On the Ontological Status of Autism: the ‘Double Empathy Problem’. Disability and Society. Vol. 27(6): 883-887.

- Wikipedia article “Double empathy problem”

- National Autistic Society article “The double empathy problem“