This article revisits Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, exploring its foundational principles and questioning its relevance in capturing the complexity of human motivation. Drawing on Robert Pirsig’s critique in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Lila: An Enquiry into Morals, Michel Foucault’s insights into societal structures, and the Japanese concept of Ikigai, it challenges the rigidity of Maslow’s model. Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality offers a dynamic alternative, emphasising fluidity, interconnectedness, and the pursuit of quality as central to human fulfilment.

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs has long been a cornerstone of psychological thought. It presents a linear progression of human motivation, from the foundational pursuit of basic survival to the lofty aim of self-actualization. Yet, as influential as this model is, it may not fully capture the intricate realities of human existence.

Robert Pirsig, the author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, challenged the rigidity of Maslow’s pyramid. While acknowledging its practicality, Pirsig argued that human needs are far more interconnected than the model suggests. The notion that creativity or self-actualization can only emerge once basic needs are fully satisfied misses the profound ways people often find purpose and meaning amid adversity.

Understanding Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

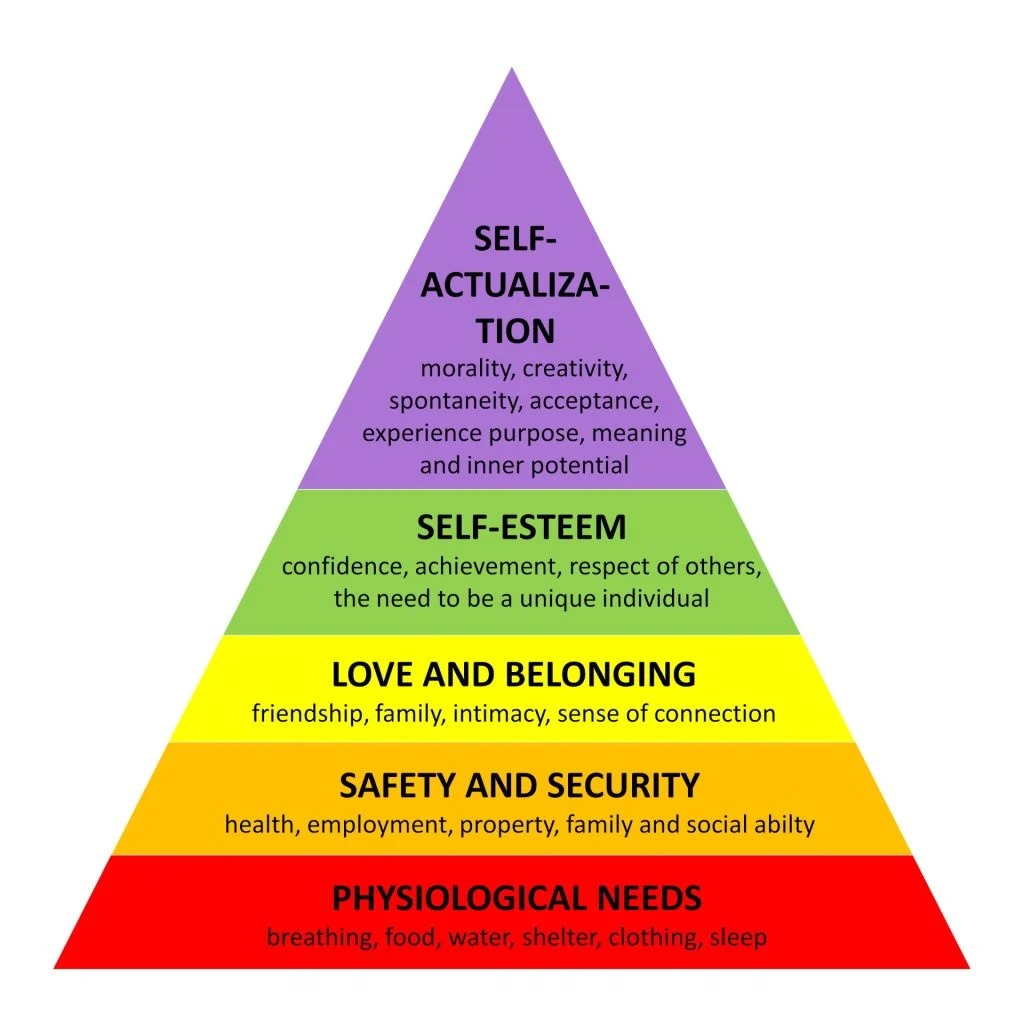

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a foundational theory in psychology that organizes human motivation into a five-tier pyramid. Introduced in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” the model posits that individuals must satisfy basic, lower-level needs before they can focus on more complex, higher-level aspirations.

The pyramid is structured as follows:

- Physiological Needs: These are the most basic requirements for survival, including food, water, shelter, and sleep. Without these, other needs cannot be pursued.

- Safety Needs: Once physiological needs are met, individuals seek security and stability, protection from physical harm, financial security, health, and a safe environment.

- Love and Belonging: After achieving safety, humans crave connection. Relationships, friendships, and a sense of community become critical.

- Esteem Needs: This level focuses on self-respect, recognition, and achievement. Individuals strive for status, confidence, and a sense of accomplishment.

- Self-Actualization: At the top of the hierarchy is the desire to reach one’s fullest potential, pursuing personal growth, creativity, and purpose.

Maslow’s theory suggests that these needs are hierarchical and sequential. The lower tiers, often called deficiency needs, must be satisfied before individuals can focus on the higher-level growth needs. For example, someone struggling to find food is unlikely to prioritize artistic expression or intellectual exploration.

While Maslow’s model has become a ubiquitous framework for understanding motivation, it is not without its critics. The structured, sequential nature of the hierarchy assumes a linear progression that may oversimplify the complexity of human life. Critics argue that individuals often pursue higher needs, like purpose or connection, even when their basic needs are unmet. This is where Robert Pirsig’s critique becomes particularly relevant.

Quality Over Hierarchy

Central to Pirsig’s philosophy is the concept of quality, an ineffable yet fundamental force that transcends rigid categories. He saw life as dynamic, messy, and nonlinear, with moments of growth and insight often arising when lower needs remain unmet. Pirsig’s critique is not just a dismissal of Maslow’s framework but an invitation to consider how value and purpose operate across all dimensions of life.

Foucault: Questioning the Pyramid

To expand on Pirsig’s critique, we can turn to Michel Foucault. Foucault’s work often explored how systems of thought, like Maslow’s hierarchy, reflect and reinforce societal power structures. From Foucault’s perspective, the hierarchy is not merely a psychological model but a cultural artefact that upholds Western ideals of individualism and progress.

The pyramid’s focus on individual self-actualization risks sidelining communal and relational aspects of fulfilment. Foucault might argue that such frameworks shape our understanding of human development in ways that serve specific socio-economic narratives, leaving little room for alternative or collective ways of living.

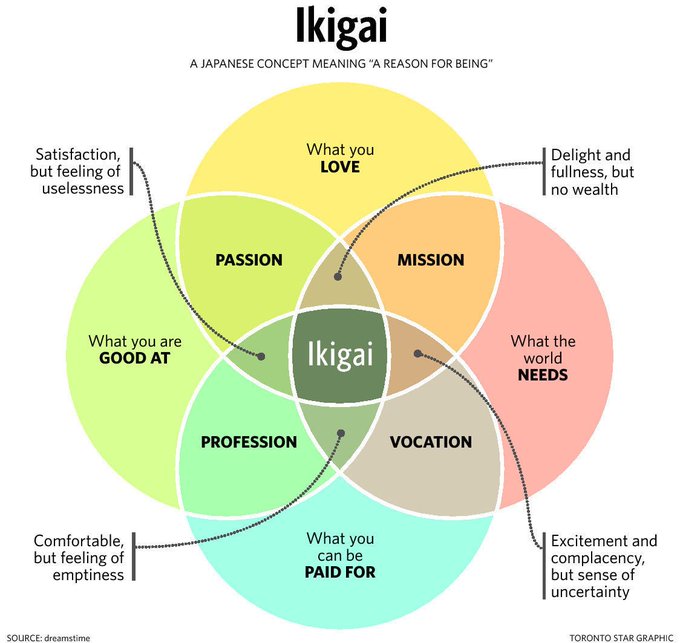

Ikigai: A Circular Approach

In contrast to Maslow’s linear hierarchy, the Japanese concept of Ikigai offers a more integrative perspective. Ikigai, often described as a “reason for being,” exists at the intersection of what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. It’s not about climbing a pyramid but harmonizing various facets of life to create meaning and fulfilment.

Ikigai aligns closely with Pirsig’s idea of quality. It suggests that purpose is not a distant goal achieved only after meeting other needs but something that can be woven into daily existence. Even in hardship, a sense of Ikigai can guide individuals toward balance and satisfaction, blurring the lines between Maslow’s “higher” and “lower” needs.

Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality: A New Framework

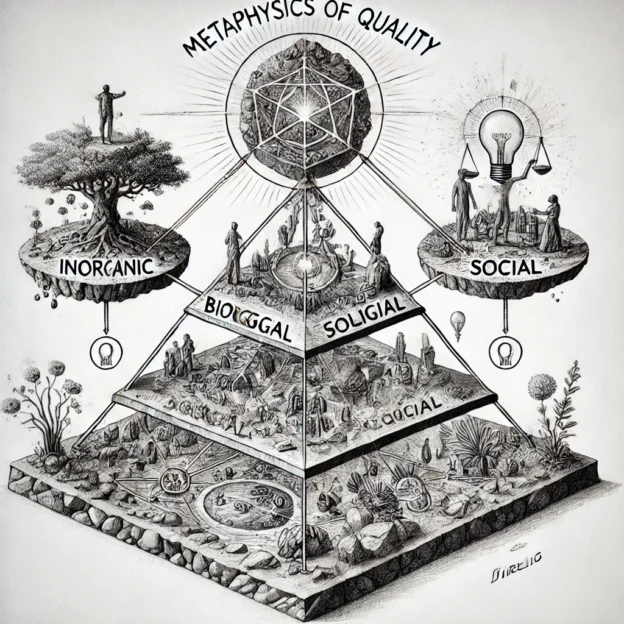

In his follow-up book, Lila: An Inquiry into Morals, Pirsig expanded his ideas into a more structured framework, the Metaphysics of Quality (MOQ). This model categorizes life into four levels of static value patterns:

- Inorganic: Physical and chemical processes.

- Biological: Life and evolutionary dynamics.

- Social: Human systems and societal norms.

- Intellectual: Ideas, reason, and knowledge.

While hierarchical in nature, Pirsig’s model is dynamic. The levels interact and often conflict; for example, intellectual freedom might challenge social norms, or biological needs might override intellectual pursuits. Importantly, Pirsig’s system is unified by the concept of quality, which transcends and connects these levels. Unlike Maslow’s rigid sequence, the Metaphysics of Quality emphasizes balance and interplay rather than linear progression.

Beyond the Pyramid

Pirsig, Foucault, and Ikigai challenge us to move beyond Maslow’s pyramid and rethink how we conceptualize human needs and aspirations. Life rarely conforms to neatly stacked hierarchies. Instead, it unfolds in a dynamic interplay of challenges, insights, and connections.

Foucault encourages us to examine the societal forces shaping psychological frameworks, while Ikigai offers a holistic alternative rooted in harmony and purpose. Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality invites us to see value not as a distant goal but as something inherent in every moment of existence.

Perhaps, as Pirsig might argue, the true fulfilment of human potential lies not in climbing a pyramid but in pursuing quality, an elusive, unquantifiable essence that weaves through all aspects of life, guiding us toward a richer and more meaningful understanding of what it means to be human.