Alan Moore, the legendary author of Watchmen and V for Vendetta, argues that fandom, once a source of passion and community, has become toxic, shaping modern culture and politics in worrying ways. He highlights the entitlement and hostility within today’s fan communities, drawing parallels to historical fandoms, from Roman gladiators to football hooligans, and calls for a return to an uplifting, creative spirit. Moore’s reflections challenge readers to rethink fandom’s role in society and its potential for both unity and division.

Introduction: Alan Moore’s Critique of Modern Fandom

In his recent reflections on fandom, “Fandom has Toxified the World“, published in the Guardian, Alan Moore raises a powerful critique of how an increasingly polarised fan culture has seeped into wider society, often with troubling effects. Moore, the celebrated author of Watchmen and V for Vendetta, has long stood apart in his critical stance on popular culture’s fixation with superheroes and the notion of celebrity within fandoms. With insights both incisive and necessary, Moore argues that today’s fandoms have toxified the social and political landscape, morphing from communities of shared enthusiasm into entities that fuel entitlement, obsession, and hostility.

The Historical Roots of Fandom and Fanaticism

Yet, while Moore’s perspective is astute, these issues are not entirely new. Fandom has been a potent force in human history for centuries, and fanaticism always could provoke conflict. Ancient Rome saw extreme fan allegiances to gladiatorial teams, the greens, reds, and blues, that often erupted into violence in the streets. Similarly, football hooliganism through the ages has shown how fans’ devotion can escalate into tribalism. Moore’s critique shines a valuable light on how fan attitudes have shifted in our digital age, but it’s worth considering how these dynamics have long existed as part of the human psyche, in varying degrees of extremity.

From Enthusiasm to Entitlement: The Shift in Fan Culture

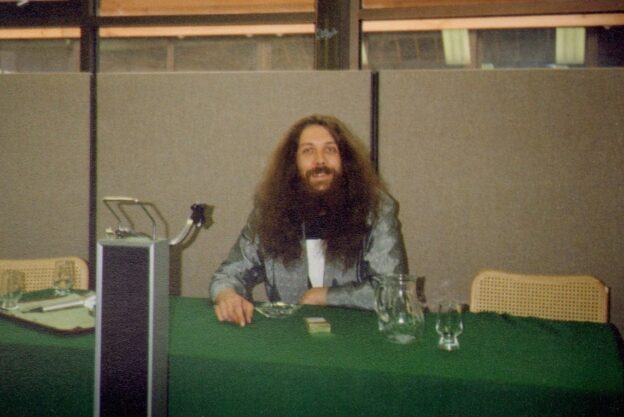

Moore recalls the early days of comic fandom as a space of enthusiastic creativity rather than hostility. He recounts a time when comic book fans, often teenagers, gathered in small, uncommercialised settings to celebrate a shared passion without the looming presence of major corporate interests. These gatherings were raw, optimistic, and untainted by the entitlement that characterises many modern fan communities. Today, however, fandom has become commercialised and professionalised, with companies often encouraging the devotion that drives sales. The once countercultural energy of comics fandom has shifted toward a more consumerist, entitlement-driven environment.

Ancient Allegiances and Modern Obsessions

However, Moore’s view could benefit from additional context. Intense fan dynamics are as ancient as the Colosseum itself. In ancient Rome, factions of spectators aligned fiercely with different gladiatorial teams, and these rivalries frequently escalated into social unrest. Gladiatorial fan groups mirrored some of today’s fan communities with their intense loyalty and identity formation, providing a kind of “bread and circuses” to distract the masses, as Juvenal put it, from the real issues at hand. Moore’s observation that fandom can cloud political judgement, blurring entertainment with governance, echoes Juvenal’s warning. Today, fans may mobilise around political figures as if they were pop culture icons, making decisions based on the “performance” of a leader rather than their policies or substance. But while Moore argues that fandom has toxified the world, this ancient tendency to align with powerful figures for the sake of belonging suggests that the impulse itself is not new, it has simply taken on a different form.

The Digital Amplification of Fan Power

What is undeniably different today is the way fandoms have adapted to the internet age, amplifying their reach and influence. Through social media, fandoms can gather, organise, and exert a greater impact on mainstream culture and politics than ever before. Moore points to fan-led crusades such as Gamergate or Comicsgate, which, through a sense of entitlement, targeted creators and fostered toxic environments online. In this sense, Moore’s critique is relevant and vital. Today’s platforms allow fandoms to transcend geography, magnifying both their power and their divisiveness. This shift transforms Moore’s analysis from a timeless critique of human nature into a call for awareness in a digitally-driven era where fan entitlement can, and often does, shape social and political outcomes.

Fandom’s Impact on Politics and Society

Even with these considerations, Moore’s reflections remain an invaluable guide to understanding the perils of a society increasingly defined by fandoms. His concerns extend beyond comic books to the realms of politics, where fan culture sometimes blurs the lines between policy and spectacle. Moore points out that public figures like Donald Trump or Boris Johnson, akin to “celebrity contestants,” often win or lose support not on policy, but on performance, a result, he suggests, of fan-like loyalty devoid of critical analysis.

A Call for Positive, Constructive Fandoms

In closing, Moore’s critique of fandom is a timely reminder of how passion can tip into toxicity when it becomes entitlement, and how entertainment can blur into ideology. He reminds us that enthusiasm, while a force for good, is most productive when grounded in contribution, creation, and a spirit of openness. Moore’s voice urges today’s fan communities to reconnect with the original energy of fandom, one that celebrates and uplifts rather than demands and disparages. His insights, grounded in his experience and wisdom, are a clarion call to ensure that fandom remains a space for collective passion, not a driver of division.