While browsing YouTube Shorts, mainly for Tacticus Tips and Warhammer 40K fan fiction, I stumbled upon a video featuring Rory Sutherland discussing the absurdity of Ferraris in central London. His thoughts on waste reminded me of a book I encountered in the school library at KEGS Aston around 1983: Vernon Lee’s Satan the Waster. This article discusses the nature of waste, drawing a comparison with Siegfried Sassoon’s At the Cenotaph. Through this lens, it explores how both Sassoon and Violet Paget (writing as Vernon Lee) critique the senselessness of war, using waste as a symbol for the destruction of human life, resources, and potential, much like how ridiculous luxury goods are symbols of impractical extravagance.

The video clip analyzing the absurdity of Ferraris in London draws attention to the connection between luxury and waste, suggesting that wastefulness is an unmistakable sign of abundance. As the speaker observes, the impracticality of owning a Ferrari in a dense urban environment gives it meaning, almost as a form of conspicuous consumption that flaunts resources. This notion of luxury being intertwined with wasteful display serves as a compelling lens to explore Violet Paget’s dramatic poem, Satan the Waster, and Siegfried Sassoon’s At the Cenotaph. Through both literary works, waste, in the context of war and humanity’s capacity for destruction, emerges as a powerful theme that critiques the senselessness of human endeavors, especially in the context of violence and conflict.

Rory Sutherland and His Insights on Luxury and Waste

Rory Sutherland is a British advertising executive and Vice Chairman of Ogilvy UK, known for his unique perspectives on human behaviour, marketing, and behavioural economics. Sutherland often challenges conventional thinking, offering insights into why people make irrational choices and how this behaviour can be harnessed in marketing. He is a leading advocate of applying behavioural science to advertising, frequently speaking about concepts like “the perception of value” and “choice architecture” to explain consumer behaviour.

Sutherland’s work frequently touches on themes of status, luxury, and the psychology behind seemingly irrational decisions. The video clip about Ferraris in central London reflects his ongoing interest in how luxury items serve as symbols of status and waste. By drawing attention to the absurdity of driving an impractical car in an urban environment, Sutherland highlights a key aspect of luxury: the more impractical or wasteful something is, the more it signifies wealth and status. This view aligns with his broader approach to behavioural science, where human preferences are often shaped not by logic but by emotional and social factors.

His wit and deep understanding of consumer psychology make Sutherland a compelling figure in both advertising and behavioural economics. He frequently uses these insights to critique modern societal values, particularly how we assign value based on perception rather than practical utility. His comparison of Ferraris and lorries in terms of status is a perfect example of this, as it underscores how value is derived not from practical functionality but from the appearance of extravagance.

Violet Paget and Her Pseudonym Vernon Lee

Violet Paget (1856–1935), better known by her male pseudonym Vernon Lee, was an English writer and intellectual whose work spanned aesthetics, cultural criticism, and ethics. Paget chose the pseudonym Vernon Lee to challenge Victorian gender norms and position herself in male-dominated intellectual circles. Her exploration of war’s wasteful nature is poignantly captured in Satan the Waster (1920), a pacifist and anti-war dramatic poem written shortly after the First World War. Through this work, Lee imagines Satan as a master manipulator who orchestrates war for his amusement, revealing how waste, death, and destruction are celebrated as part of humanity’s tragic history.

Vernon Lee’s “Satan the Waster” depicts the horrors of the First World War, reflecting on war as an extravagant and wasteful spectacle orchestrated by Satan. The play is deeply philosophical, critiquing the futility of war and how mankind’s readiness to destroy one another mirrors the wastefulness of luxury described in the video. Just as the speaker in the video identifies luxury in the wastefulness of owning a Ferrari in central London, so too does Lee explore war as the ultimate waste, a wasteland of human life, resources, and potential. The war itself becomes a grotesque display of excess, devoid of any real purpose other than to showcase mankind’s capacity for destruction.

The Waste of War in Satan the Waster

Written just after World War I, Satan the Waster presents a pacifist critique of war, using Satan as a symbol of war’s futile and wasteful nature. Satan, in Lee’s dramatic poem, is not merely a force of evil but a master of manipulation, goading humanity into conflict for his own amusement. War, in Lee’s hands, becomes the ultimate symbol of human wastefulness, not unlike the Ferrari in London, the very act of waging war is a display of resources, energy, and life expended without reason. Lee’s Satan watches gleefully as human beings destroy themselves, knowing full well that the destruction is, at its core, meaningless.

Lee’s exploration of waste as inherent to war mirrors the idea from the video that luxury is bound to impracticality. Just as the impracticality of the Ferrari gives it meaning, the absurdity of war gives it a tragic significance. For Lee, war is not a noble pursuit or a defence of ideals, but rather a spectacle of human wastefulness, driven by the same irrational desires that drive people to flaunt luxury through impractical means.

Siegfried Sassoon and the Haunting Legacy of War

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) was a British soldier, poet, and writer, known for his poignant and often bitter poetry that captured the horrors of war. A decorated soldier during the First World War, Sassoon became a vocal critic of the war’s conduct, writing powerful anti-war poetry that resonated with a generation disillusioned by the senseless violence and destruction.

Sassoon’s poetry is deeply rooted in his personal experiences on the front lines. His works often reflect the waste of human life and the futility of war, themes that align with his later work, At the Cenotaph (1946), written after the Second World War. At the Cenotaph is a solemn reflection on war’s lingering impact, where Satan asks God to let humanity forget the horrors of conflict. In this poem, Sassoon explores the tension between memory and forgetting, drawing attention to how easily humanity might slip back into destructive habits if the lessons of the past are not preserved.

At the time of writing At the Cenotaph, Sassoon was grappling with the trauma of two world wars. Having already lived through the First World War, which shaped his literary identity, the Second World War further reinforced his sense of disillusionment. Though no longer a soldier, he remains haunted by the wastefulness of war, as his poem reflects a deep yearning for humanity to remember and learn from the past. Sassoon’s life, marked by his vocal pacifism and his struggle to reconcile the atrocities of war with the values of society, is key to understanding the emotional weight of his later works. His perspective was no longer that of a young soldier but of a mature poet who had seen humanity’s tendency to repeat its mistakes.

Sassoon’s life after the First World War was also marked by personal struggles, including grappling with his identity and the loss of close friends in the war. His later years saw him retreat into more solitary pursuits, though his work continued to resonate with generations confronting the trauma of global conflicts. His enduring concern for the wastefulness of war, expressed in At the Cenotaph, reveals his deep-seated fear that mankind might never fully escape the destructive cycles of violence.

War Before and After: The Context of the First and Second World Wars

Both Satan the Waster and At the Cenotaph were written in response to the two world wars, but their perspectives differ due to their historical contexts. Satan the Waster, written in 1920, immediately after the First World War, captures the raw horror and disbelief at the senseless waste of life that the war had caused. Lee’s use of Satan as a character highlights the deliberate manipulation and waste that war entails, suggesting that war is never justified but rather a perverse expression of human excess.

By contrast, At the Cenotaph is a reflection on memory and the passage of time. Written after the Second World War, Sassoon’s poem carries a tone of resignation and sorrow. Sassoon seems to acknowledge that while wars are wasteful, humanity is equally wasteful in its refusal to learn from its mistakes. The two works together create a timeline of human wastefulness, Lee’s work critiquing the immediate devastation of war, and Sassoon’s work mourning humanity’s failure to remember that devastation.

Conclusion: Waste, Satan, and the Human Condition Across Time

The video’s reflection on luxury as a form of waste serves as an apt starting point for considering Satan the Waster and At the Cenotaph. Just as luxury items like Ferraris in London are absurd displays of wealth and wastefulness, so too are wars wasteful displays of humanity’s worst instincts. Violet Paget’s Satan the Waster and Siegfried Sassoon’s At the Cenotaph both grapple with this notion of waste, Paget in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, focusing on the destruction wrought by human folly, and Sassoon after the Second World War, reflecting on humanity’s capacity to forget its own destructive nature. Together, these works remind us that war, like luxury, is a spectacle of waste that serves no meaningful purpose beyond satisfying humanity’s irrational desires.

Beyond these literary works, Satan has often been used as a symbol of waste and destruction across different contexts, particularly in religious and literary traditions. In the Book of Job, Satan acts as a tester of faith, but also as an agent of waste and ruin. By challenging God to test Job’s faith, Satan instigates the destruction of Job’s livelihood, health, and family. While the story focuses on Job’s endurance, the vast human and material waste caused by Satan’s interventions cannot be overlooked. Job’s suffering, inflicted for the sake of a celestial bet, exemplifies how Satan orchestrates waste for reasons that transcend human understanding, highlighting the randomness and destructiveness that often accompany wastefulness.

Similarly, in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, Satan appears in the form of Woland, a mysterious foreigner who wreaks havoc on Soviet society. While Woland’s actions appear whimsical and chaotic, his role in the novel is more nuanced. Woland exposes the absurdities, hypocrisies, and moral decay of the society he visits, but he does so through wasteful and destructive means. The magic shows and theatrical disasters he stages serve as both spectacle and critique, forcing society to confront its own spiritual and moral emptiness. Here, Satan becomes a figure of wasteful excess, exposing the hollowness of a world obsessed with materialism and shallow values. Woland’s wastefulness, much like the Ferrari in central London, is both a spectacle and a symbol, an extravagant show that critiques the very society that prizes excess over substance.

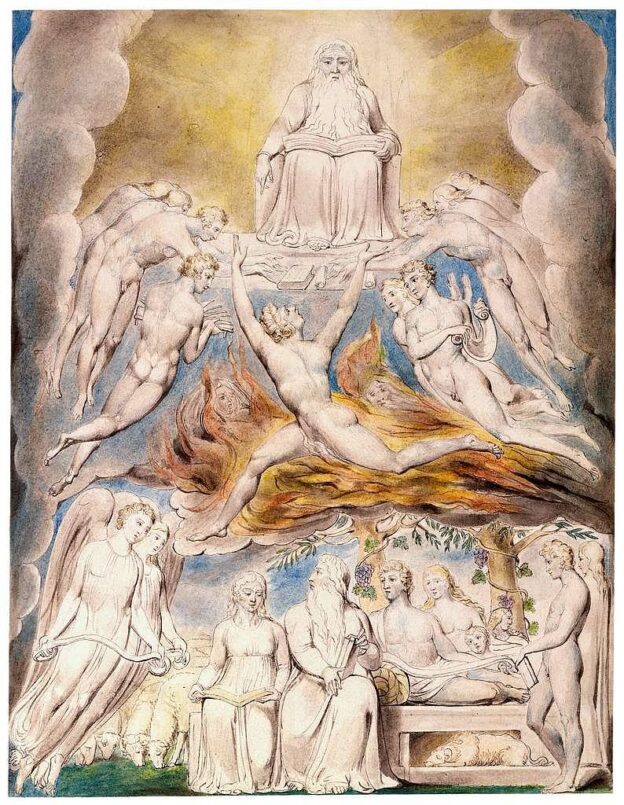

Other literary depictions of Satan or satanic figures similarly emphasize waste. In John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan’s rebellion against God leads to the ultimate cosmic waste, his fall from grace, along with that of his followers, results in a war that accomplishes nothing but eternal damnation. The waste of heavenly resources and angelic potential echoes throughout the poem, with Satan himself embodying wasted ambition and misguided pride. Satan’s desire for power results in nothing but destruction, both for himself and the cosmos.

In Goethe’s Faust, Mephistopheles, a figure often interpreted as a satanic character, also represents waste, particularly of human potential. He tempts Faust with worldly pleasures, leading him down a path of indulgence and excess, but the result is a squandering of Faust’s intellectual and spiritual potential. Like Satan in Satan the Waster or Woland in The Master and Margarita, Mephistopheles plays on humanity’s desires, pushing Faust toward wasteful and ultimately self-destructive choices.

These various depictions of Satan illustrate how the theme of waste transcends individual works and genres. Whether through war, material excess, or the destruction of spiritual potential, Satan often acts as an agent of waste, encouraging humanity to squander its resources, values, and ambitions. This concept of Satan as a figure of waste ties together these seemingly disparate literary works, offering a powerful critique of human tendencies toward destruction, indulgence, and folly. Whether in Paget’s depiction of war, Sassoon’s reflections on memory, or Sutherland’s analysis of luxury, the connection between waste and Satan serves as a reminder of humanity’s capacity for self-destruction and the importance of confronting these tendencies head-on.