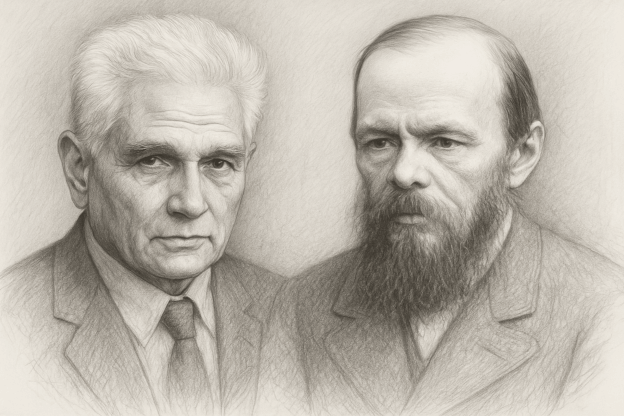

This article explores Fyodor Dostoevsky’s literary and philosophical contributions through a deconstructive lens, guided by the thought of Jacques Derrida. The aim is not to superimpose Derrida upon Dostoevsky as if one were merely a tool to decode the other, but rather to explore the dialogic potential of their proximity, where the one haunts, and is haunted by, the other.

Introduction: On the Threshold of Meaning

If Derrida’s project is, at its heart, concerned with the instability of meaning, the slippage of signifiers, and the impossibility of final presence, then Dostoevsky stands as a literary precursor whose narratives stage this impossibility with brutal psychological acuity. In Dostoevsky’s world, the self is never one, the word never full, the law always already breached. We are not merely reading novels; we are undergoing a violent deconstruction of the Western subject.

This article will read Dostoevsky’s key works, notably The Brothers Karamazov, The Double, and Notes from Underground, as a prefiguration of Derridean différance, trace, and aporia. In doing so, it asks: What happens when the Christian existentialist of the 19th century is placed beside the Jewish post-structuralist of the 20th? Might they both be resisting the same metaphysical seductions, albeit in profoundly different idioms?

I. The Self as Trace: The Double and the Deconstruction of Identity

In Derrida’s Of Grammatology, the subject is not a sovereign originator of meaning but is itself a product of deferral and difference, a trace rather than a presence. Dostoevsky’s The Double enacts precisely this insight.

Golyadkin’s psychic collapse is not a descent into madness in the psychiatric sense, but a literary staging of the impossibility of a unified subject. The “double” is not merely his doppelgänger; he is the articulation of différance made flesh. He is everything Golyadkin is not, and yet cannot exist without him.

Derrida teaches us that identity is never pure, but always contaminated by the other it excludes. Golyadkin’s descent is thus the Derridean nightmare: the other that haunts the self is not outside it, but the condition of its very possibility. The sovereign self, always an illusion, collapses when faced with its own structural duplication.

II. Aporia and the Underground Man

In Notes from Underground, Dostoevsky gives us perhaps the clearest instance of what Derrida might call an aporia, an impasse that cannot be resolved within the system it inhabits.

The Underground Man’s endless self-negation, his self-aware descent into spite, perversity, and inaction, mirrors the Derridean recognition that the logocentric subject cannot ground itself. He simultaneously craves freedom and is paralysed by it. He knows he contradicts himself and delights in it. This is not irony, but aporia: the very condition of thinking within, yet against, the metaphysical system.

What Derrida reveals about Western metaphysics, that it is built on binary oppositions, and that these oppositions collapse upon closer inspection, is already being lived, painfully, by the Underground Man.

He is not simply a character; he is a deconstructive principle incarnate.

III. Law and Transgression: The Brothers Karamazov and the Différance of God

In The Brothers Karamazov, the famous Grand Inquisitor episode stages not merely a critique of the Church or Christendom but a deconstruction of divine authority itself. Ivan Karamazov’s rebellion, his refusal to accept a cosmos that allows the suffering of children, articulates a rupture at the heart of theodicy. But more than this, it challenges the very stability of the sign “God”.

For Derrida, God is the ultimate metaphysical presence, the guarantor of meaning, order, and morality. Yet in Ivan’s vision, this God is revealed as absent, silent, or worse, complicit. Alyosha’s faith is a kind of deferred presence; it does not answer but endures.

Here we may recall Derrida’s insistence that justice, unlike law, is always to come, à venir. Like Derrida’s notion of messianicity without messianism, Dostoevsky’s faith is never doctrinal, never finalised, but oriented toward a future that cannot be codified. The Karamazovian hope is therefore not a resolution but a tension between justice and the Law, between God and silence, between suffering and meaning. This is différance in theological form.

IV. Writing and Haunting: The Spectral Ethics of Dostoevsky

Derrida often returns to the figure of the spectre, the ghost who haunts without resolution (Spectres of Marx). In Dostoevsky, the spectral is everywhere. Whether it is the ghost of Fyodor Pavlovich in The Brothers Karamazov, the lingering presence of the murdered pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment, or the metaphysical restlessness of Raskolnikov’s conscience, we are never far from what Derrida might call the “hauntological”.

Dostoevsky does not offer redemption without residue. Every attempt to confess, redeem, or atone is always already infected by its opposite. The murder that finds meaning (Raskolnikov kills to test his theory) is also its unravelling. Meaning is deferred, never full.

This is not an accident of plot, but a structural truth. The subject is haunted. The word is haunted. The divine is haunted. Dostoevsky writes, as Derrida might say, “under erasure.”

V. Standing on the Shoulders: Nina Straus, Dostoevsky’s Derrida, and the Double-Voiced Messianic Trace

In her seminal essay, “Dostoevsky’s Derrida” (Common Knowledge, 2002), Nina Straus highlights the uncanny philosophical resonance between Fyodor Dostoevsky and Jacques Derrida, two writers separated by centuries but united by a shared preoccupation with undecidability, ethical witnessing, and the agonistic demands of faith.

Straus writes:

“Dostoevsky’s characteristically polyphonic, double-voiced diction (‘even if the truth were outside Christ’) is echoed in Derrida’s ‘perhaps even’ in a passage where Derrida commits himself to a mystical messianism.”

This echo is not incidental. It is a philosophical homology between Dostoevsky’s refusal to collapse faith into certainty and Derrida’s late turn toward a kind of mystical aporia—what he calls “the impossible” in Circumfession, his quasi-confessional meditation on death, faith, and language. Straus situates this shift within the lineage of Western thought: Abraham, Augustine, Kierkegaard, and Levinas form Derrida’s explicit genealogy, but it is Dostoevsky, as Straus shows, who looms spectrally in the background, an “absent presence” in Derrida’s canon of undecidable belief.

VI. Unfinalised: Where Every Thought Interrupts, Every Voice Collides

This version preserves the Bakhtinian root of “unfinalised” while giving it momentum and density, evoking the cacophony of Dostoevskian characters, Derrida’s aporetic spirals, and Baudrillardian signal overflow. It sets the tone for what follows: a space where dialogue becomes interruption, and certainty gives way to contradiction.

What Bakhtin identified as Dostoevsky’s “dialogic discourse”, where voices collide, contradict, and refuse closure, mirrors Derrida’s own refusal of the final signified. Straus notes that Dostoevsky’s rendering of God as merely one voice among many in an unfinished dialogue anticipates Derrida’s move to a “witness” structure, where the divine is no longer a metaphysical anchor but a haunted interlocutor.

Indeed, in Circumfession, Derrida writes:

“I am addressing myself here to God, the only one I take as a witness, without yet knowing what these sublime words mean…”

Here, Derrida does not confess to God, but rather to the grammar of God, to the structure of an impossible name. Straus compellingly aligns this with Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov, who also flounders under the weight of such an address, teetering between negation and longing.

Straus goes further, suggesting that both Derrida’s post-1992 writings and Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer are haunted by the same impulse: a vision of universal emancipation that seeks to fuse religious mysticism with political urgency, without ever allowing either pole to dominate or settle. In this messianic register, both thinkers are united, not as metaphysical system builders, but as chroniclers of a struggle where faith, ethics, and language perpetually defer closure.

Straus’s analysis is pivotal not simply because it draws Dostoevsky into Derrida’s orbit, but because it shows that Derrida’s deconstruction, often caricatured as relativistic, might instead be understood as a radical faithfulness to polyphony: a fidelity to what is excluded, to what interrupts, to what remains to come.

VII. Beyond Presence: Forgiveness, Confession, and Writing

Derrida’s late writings on forgiveness, hospitality, and confession are particularly apt for Dostoevsky. In On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness, Derrida distinguishes between conditional and unconditional forgiveness, just as Dostoevsky distinguishes between juridical confession and spiritual repentance.

Confession in Crime and Punishment is not a simple act of speech, but a metaphysical ordeal. Sonia does not demand Raskolnikov’s punishment; she demands his suffering, that he feel his guilt, not simply admit it. This echoes Derrida’s view that true forgiveness must forgive the unforgivable; otherwise, it is merely a transaction.

And so we return to language. In both Dostoevsky and Derrida, language fails, and yet it is all we have. The word cannot close the gap it names, but in naming it, it opens the possibility of an ethical encounter. Not presence, but responsibility.

Conclusion: Toward a Shared Incoherence

To read Dostoevsky through Derrida is not to reduce literature to philosophy or to instrumentalise theory. It is, rather, to acknowledge a shared discomfort with closure, with systems that claim to say it all. Both writers refuse easy synthesis.

Dostoevsky’s theology is not doctrinaire but interrogative. His characters pray, curse, love, and betray in the full knowledge that meaning is never settled. Derrida does not destroy meaning; he delays it, questions it, leaves it trembling. In this trembling, Dostoevsky was already a master.

And so, we might say: the deconstruction was already there, in the double, in the underground, in the silence of God. All Derrida did was give it a name.

References (Selected):

- Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference.

- Derrida, Jacques. Spectres of Marx.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Notes from Underground.

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Double.

- Kearney, Richard. Strangers, Gods and Monsters.

- Blanchot, Maurice. The Space of Literature.

- Straus, Nina. “Dostoevsky’s Derrida.” Common Knowledge 8, no. 3 (2002): 555–567.

DOI:10.1215/0961754X-8-3-555