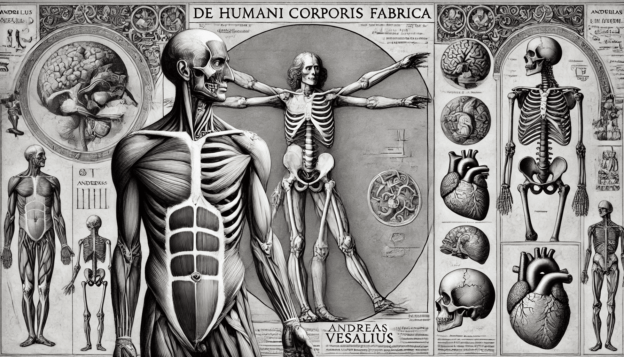

Andreas Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica revolutionised the study of human anatomy by challenging Galenic orthodoxy through direct observation and dissection. Published in 1543, the Fabrica corrected centuries-old inaccuracies, introduced detailed anatomical illustrations, and established a new empirical approach to medical science. This landmark work remains a cornerstone in the history of medicine and a testament to the power of observation and critical inquiry.

In the annals of medical history, few figures loom as large as Andreas Vesalius, the Flemish physician and anatomist who authored De humani corporis fabrica (commonly referred to as the Fabrica). Published in 1543, this monumental work fundamentally altered the course of anatomical science, establishing Vesalius as a pioneer of evidence-based medicine. The Fabrica remains a landmark in the history of both medicine and publishing, bridging the Renaissance’s humanist ideals with the practical demands of scientific inquiry.

Contents

The Context: Anatomy Before Vesalius

Before Vesalius, the study of human anatomy was largely constrained by reverence for ancient authorities, particularly the 2nd-century Greek physician Galen. Galen’s anatomical descriptions, derived from animal dissections, dominated European medical teaching for centuries. However, his reliance on non-human specimens, primarily monkeys and pigs, led to inaccuracies when applied to human anatomy.

Anatomy was taught primarily through textual recitation rather than hands-on observation. Students would listen as lecturers read from Galen’s texts while an assistant conducted dissections. This division of labour insulated the learned physician from the messier, empirical aspects of anatomy, perpetuating an uncritical acceptance of errors.

Why Was Vesalius Revolutionary?

Andreas Vesalius was revolutionary because he rejected the passive acceptance of inherited knowledge and championed the empirical study of anatomy. His insistence on dissecting human cadavers, rather than relying on ancient texts or animal dissections, exposed significant errors in the works of Galen, the preeminent authority on anatomy for over a millennium. Vesalius did not merely revise anatomical understanding; he redefined the very process of acquiring knowledge. He embodied the Renaissance spirit of questioning tradition, favouring observation and experimentation over blind faith in authority.

Challenging Societal Norms

In addition to challenging medical orthodoxy, Vesalius defied societal and religious norms of his era. Human dissection was controversial, often considered taboo and closely regulated by both the Church and secular authorities. Although some Renaissance cities permitted dissection for educational purposes, cadavers were scarce, often obtained through dubious or clandestine means. Vesalius’s public dissections and unflinching exploration of the human body were seen by many as transgressive acts that desecrated the dead.

Furthermore, Vesalius challenged the hierarchical division between the learned physician and the manual labourer. By personally conducting dissections, Vesalius bridged the gap between theoretical and practical medicine, asserting that true understanding required hands-on experience.

Without the Fabrica, Where Would We Be?

Had the Fabrica never been published, the evolution of modern anatomy and medicine might have been significantly delayed. The work not only corrected longstanding misconceptions but also established a culture of rigorous inquiry that became the foundation of scientific medicine. Without Vesalius’s insistence on first-hand observation, medical education might have continued to stagnate under the weight of unchallenged authority, leaving many critical discoveries unrealised for centuries.

Moreover, the Fabrica influenced the broader scientific revolution, demonstrating the importance of integrating empirical methods with clear communication. The illustrations alone set a new standard for scientific publishing, showing how visual aids could convey complex information effectively.

De humani corporis fabrica: An Overview and Critique

The Fabrica, published when Vesalius was just 28, comprises seven books, each addressing a different aspect of human anatomy. Its scope and ambition were unparalleled, covering skeletal structures, muscles, blood vessels, nerves, and internal organs with unprecedented detail.

Book I: The Bones

This foundational section details the human skeletal system. Vesalius meticulously describes the bones, their structure, and their relationships to one another. He also corrects several Galenic errors, such as the composition of the jawbone and the shape of the sternum.

Critique: While thorough, the text occasionally dwells on minutiae, which can detract from its broader applicability. However, the vivid illustrations compensate for this, offering a clear and practical reference for students and practitioners.

Book II: The Muscles

Here, Vesalius explores the muscular system, providing detailed descriptions of individual muscles and their functions. He also includes instructions for preparing cadavers to observe specific structures.

Critique: The focus on dissection techniques makes this section particularly valuable for anatomists. However, the lack of a unified theory connecting muscle function to bodily movement could leave readers wanting more.

Book III: The Vascular System

This section covers the circulatory system, including veins, arteries, and the heart. Vesalius debunks Galen’s claim that blood flows between the ventricles of the heart through invisible pores.

Critique: Although Vesalius advances anatomical understanding, he does not fully grasp the concept of blood circulation, later elucidated by William Harvey. This limitation reflects the constraints of 16th-century science rather than a failing on Vesalius’s part.

Book IV: The Nervous System

Vesalius examines the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves, providing detailed descriptions of their anatomy and attempting to connect them to sensory and motor functions.

Critique: While impressive for its time, Vesalius’s understanding of neural function was rudimentary. His descriptions of the brain’s structure are more observational than interpretive.

Book V: The Abdominal Organs

This section focuses on the digestive and excretory systems, including the stomach, intestines, liver, and kidneys. Vesalius corrects Galenic misconceptions, such as the arrangement of the liver’s lobes.

Critique: Vesalius’s insights into abdominal anatomy are significant, but his limited understanding of physiological processes weakens the section’s explanatory power.

Book VI: The Thoracic Organs

Here, Vesalius describes the lungs, heart, and associated structures. He challenges Galenic notions of pulmonary function, though he does not yet arrive at modern understandings of respiration.

Critique: The illustrations in this section are particularly striking, highlighting the complexity of thoracic anatomy. However, the text reflects the transitional state of knowledge in Vesalius’s time.

Book VII: The Brain

The final book focuses exclusively on the brain and cranial nerves. Vesalius’s descriptions of the brain’s anatomy are among the most detailed of his era.

Critique: While the anatomical descriptions are groundbreaking, Vesalius’s lack of understanding of brain function limits the section’s practical utility. Nevertheless, it laid the groundwork for future neurological studies.

The Enduring Legacy of Vesalius

The Fabrica is not without its flaws; its explanations are sometimes constrained by the scientific limitations of its time. However, its strengths far outweigh its shortcomings. By combining precise observation with artistic excellence, Vesalius set a standard for medical texts that endures to this day.

Andreas Vesalius’s challenge to tradition and authority reminds us of the importance of questioning established knowledge and embracing empirical investigation. The Fabrica continues to stand as a testament to the transformative power of curiosity and innovation. It serves not only as a historical milestone but also as a lasting inspiration for all who seek to understand the complexities of the human body.

Conclusion

The Fabrica not only transformed the understanding of human anatomy but also reshaped the methodology of scientific inquiry. Vesalius’s insistence on empirical observation and his willingness to challenge established norms laid the groundwork for modern medical science. His work continues to inspire, reminding us that progress often requires questioning tradition and embracing hands-on exploration. The Fabrica endures as a remarkable fusion of art and science, reflecting the Renaissance ideal of combining beauty with knowledge.